(Mohan Malik is a professor in Asian security at Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, in Honolulu. The views expressed are his own. His most recent book is China and India: Great Power Rivals. This article was published in World Affairs, May/June 2013 issue.)

Subi Reef located near Pagasa Island (taken over by China during their creeping invasions)

The Spratly Islands—not so long ago known primarily as a rich fishing ground—have turned into an international flashpoint as Chinese leaders insist with increasing truculence that the islands, rocks, and reefs have been, in the words of Premier Wen Jiabao, “China’s historical territory since ancient times.” Normally, the overlapping territorial claims to sovereignty and maritime boundaries ought to be resolved through a combination of customary international law, adjudication before the International Court of Justice or the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, or arbitration under Annex VII of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). While China has ratified UNCLOS, the treaty by and large rejects “historically based” claims, which are precisely the type Beijing periodically asserts. On September 4, 2012, China’s foreign minister, Yang Jiechi, told US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton that there is “plenty of historical and jurisprudence evidence to show that China has sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea and the adjacent waters.”

China’s claim to the Spratlys on the basis of history runs aground on the fact that the region’s past empires did not exercise sovereignty. In pre-modern Asia, empires were characterized by undefined, unprotected, and often changing frontiers. The notion of suzerainty prevailed. Unlike a nation-state, the frontiers of Chinese empires were neither carefully drawn nor policed but were more like circles or zones, tapering off from the center of civilization to the undefined periphery of alien barbarians. More importantly, in its territorial disputes with neighboring India, Burma, and Vietnam, Beijing always took the position that its land boundaries were never defined, demarcated, and delimited. But now, when it comes to islands, shoals, and reefs in the South China Sea, Beijing claims otherwise. In other words, China’s claim that its land boundaries were historically never defined and delimited stands in sharp contrast with the stance that China’s maritime boundaries were always clearly defined and delimited. Herein lies a basic contradiction in the Chinese stand on land and maritime boundaries which is untenable. Actually, it is the mid-twentieth-century attempts to convert the undefined frontiers of ancient civilizations and kingdoms enjoying suzerainty into clearly defined, delimited, and demarcated boundaries of modern nation-states exercising sovereignty that lie at the center of China’s territorial and maritime disputes with neighboring countries. Put simply, sovereignty is a post-imperial notion ascribed to nation-states, not ancient empires.

China’s present borders largely reflect the frontiers established during the spectacular episode of eighteenth-century Qing (Manchu) expansionism, which over time hardened into fixed national boundaries following the imposition of the Westphalian nation-state system over Asia in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Official Chinese history today often distorts this complex history, however, claiming that Mongols, Tibetans, Manchus, and Hans were all Chinese, when in fact the Great Wall was built by the Chinese dynasties to keep out the northern Mongol and Manchu tribes that repeatedly overran Han China; the wall actually represented the Han Chinese empire’s outer security perimeter. While most historians see the onslaught of the Mongol hordes led by Genghis Khan in the early 1200s as an apocalyptic event that threatened the very survival of ancient civilizations in India, Persia, and other nations (China chief among them), the Chinese have consciously promoted the myth that he was actually “Chinese,” and therefore all areas that the Mongols (the Yuan dynasty) had once occupied or conquered (such as Tibet and much of Central and Inner Asia) belong to China. China’s claims on Taiwan and in the South China Sea are also based on the grounds that both were parts of the Manchu empire. (Actually, in the Manchu or Qing dynasty maps, it is Hainan Island, not the Paracel and Spratly Islands, that is depicted as China’s southern-most border.) In this version of history, any territory conquered by “Chinese” in the past remains immutably so, no matter when the conquest may have occurred.

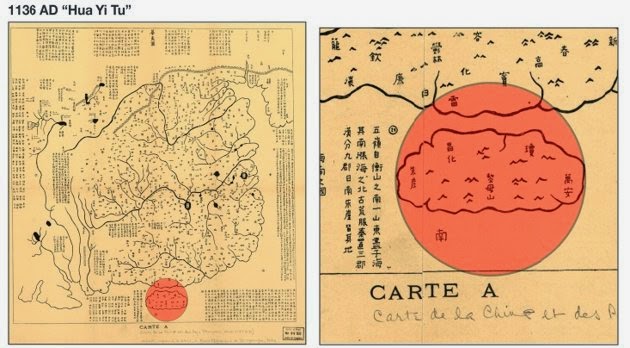

Below were ancient Chinese maps showing Paracels, Maclessfiels,

and Spratlys were not part of China.

and Spratlys were not part of China.

Such

writing and rewriting of history from a nationalistic perspective to promote

national unity and regime legitimacy has been accorded the highest priority by

China’s rulers, both Nationalists and Communists. The Chinese Communist Party

leadership consciously conducts itself as the heir to China’s imperial legacy,

often employing the symbolism and rhetoric of empire. From primary-school

textbooks to television historical dramas, the state-controlled information

system has force-fed generations of Chinese a diet of imperial China’s

grandeur. As the Australian Sinologist Geremie Barmé points out, “For decades

Chinese education and propaganda have emphasized the role of history in the

fate of the Chinese nation-state . . . While Marxism-Leninism and Mao Thought

have been abandoned in all but name, the role of history in China’s future

remains steadfast.” So much so that history has been refined as an instrument

of statecraft (also known as “cartographic aggression”) by state-controlled

research institutions, media, and education bodies.

China

uses folklore, myths, and legends, as well as history, to bolster greater

territorial and maritime claims. Chinese textbooks preach the notion of the Middle

Kingdom as being the oldest and most advanced civilization that was at the very

center of the universe, surrounded by lesser, partially Sinicized states in

East and Southeast Asia that must constantly bow and pay their respects.

China’s version of history often deliberately blurs the distinction between

what was no more than hegemonic influence, tributary relationships, suzerainty,

and actual control. Subscribing to the notion that those who have mastered the

past control their present and chart their own futures, Beijing has always

placed a very high value on “the history card” (often a revisionist

interpretation of history) in its diplomatic efforts to achieve foreign policy

objectives, especially to extract territorial and diplomatic concessions from

other countries. Almost every contiguous state has, at one time or another,

felt the force of Chinese arms—Mongolia, Tibet, Burma, Korea, Russia, India,

Vietnam, the Philippines, and Taiwan—and been a subject of China’s revisionist

history. As Martin Jacques notes in When China Rules the World, “Imperial

Sinocentrism shapes and underpins modern Chinese nationalism.”

If the

idea of national sovereignty goes back to seventeenth-century Europe and the

system that originated with the Treaty of Westphalia, the idea of maritime

sovereignty is largely a mid-twentieth-century American concoction China has

seized upon to extend its maritime frontiers. As Jacques notes, “The idea of

maritime sovereignty is a relatively recent invention, dating from 1945 when the

United States declared that it intended to exercise sovereignty over its

territorial waters.” In fact, the UN’s Law of the Sea agreement represented the

most prominent international effort to apply the land-based notion of

sovereignty to the maritime domain worldwide—although, importantly, it rejects

the idea of justification by historical right. Thus although Beijing claims

around eighty percent of the South China Sea as its “historic waters” (and is

now seeking to elevate this claim to a “core interest” akin with its claims on

Taiwan and Tibet), China has, historically speaking, about as much right to

claim the South China Sea as Mexico has to claim the Gulf of Mexico for its

exclusive use, or Iran the Persian Gulf, or India the Indian Ocean.

Ancient

empires either won control over territories through aggression, annexation, or

assimilation or lost them to rivals who possessed superior firepower or

statecraft. Territorial expansion and contraction was the norm, determined by

the strength or weakness of a kingdom or empire. The very idea of “sacred

lands” is ahistorical because control of territory was based on who grabbed or

stole what last from whom. The frontiers of the Qin, Han, Tang, Song, and Ming

dynasties waxed and waned throughout history. A strong and powerful imperial

China, much like czarist Russia, was expansionist in Inner Asia and Indochina

as opportunity arose and strength allowed. The gradual expansion over the

centuries under the non-Chinese Mongol and Manchu dynasties extended imperial China’s

control over Tibet and parts of Central Asia (now Xinjiang), Taiwan, and

Southeast Asia. Modern China is, in fact, an “empire-state” masquerading as a

nation-state.

If

China’s claims are justified on the basis of history, then so are the

historical claims of Vietnamese and Filipinos based on their histories.

Students of Asian history know, for instance, that Malay peoples related to

today’s Filipinos have a better claim to Taiwan than Beijing does. Taiwan was

originally settled by people of Malay-Polynesian descent—ancestors of the

present-day aborigine groups—who populated the low-lying coastal plains. In the

words of noted Asia-watcher Philip Bowring, writing last year in the South

China Morning Post, “The fact that China has a long record of written history

does not invalidate other nations’ histories as illustrated by artifacts,

language, lineage and genetic affinities, the evidence of trade and travel.”

Unless one subscribes to the notion of Chinese exceptionalism, imperial China’s

“historical claims” are as valid as those of other kingdoms and empires in

Southeast and South Asia. China laying claim to the Mongol and Manchu empires’

colonial possessions would be equivalent to India laying claim to Afghanistan,

Bangladesh, Burma, Malaysia (Srivijaya), Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka on the

grounds that they were all parts of either the Maurya, Chola, or the Moghul and

the British Indian empires.

China’s

claims in the South China Sea are also a major shift from its longstanding

geopolitical orientation to continental power. In claiming a strong maritime

tradition, China makes much of the early-fifteenth-century expeditions of Zheng

He to the Indian Ocean and Africa. But, as Bowring points out, “Chinese were

actually latecomers to navigation beyond coastal waters. For centuries, the

masters of the oceans were the Malayo-Polynesian peoples who colonized much of

the world, from Taiwan to New Zealand and Hawaii to the south and east, and to

Madagascar in the west. Bronze vessels were being traded with Palawan, just

south of Scarborough, at the time of Confucius. When Chinese Buddhist pilgrims

like Faxian went to Sri Lanka and India in the fifth century, they went in

ships owned and operated by Malay peoples. Ships from what is now the

Philippines traded with Funan, a state in what is now southern Vietnam, a

thousand years before the Yuan dynasty.”

And

finally, China’s so-called “historic claims” to the South China Sea are

actually not “centuries old.” They only go back to 1947, when Chiang Kai-shek’s

nationalist government drew the so-called “eleven-dash line” on Chinese maps of

the South China Sea, enclosing the Spratly Islands and other chains that the

ruling Kuomintang party declared were now under Chinese sovereignty. Chiang

himself, saying he saw German fascism as a model for China, was fascinated by

the Nazi concept of an expanded Lebensraum (“living space”) for the Chinese

nation. He did not have the opportunity to be expansionist himself because the

Japanese put him on the defensive, but cartographers of the nationalist regime

drew the U-shape of eleven dashes in an attempt to enlarge China’s “living

space” in the South China Sea. Following the victory of the Chinese Communist

Party in the civil war in 1949, the People’s Republic of China adopted this cartographic

coup, revising Chiang’s notion into a “nine-dash line” after erasing two dashes

in the Gulf of Tonkin in 1953.

Since

the end of the Second World War, China has been redrawing its maps, redefining

borders, manufacturing historical evidence, using force to create new

territorial realities, renaming islands, and seeking to impose its version of

history on the waters of the region. The passage of domestic legislation in

1992, “Law on the Territorial Waters and Their Contiguous Areas,” which claimed

four-fifths of the South China Sea, was followed by armed skirmishes with the

Philippines and Vietnamese navies throughout the 1990s. More recently, the

dispatch of large numbers of Chinese fishing boats and maritime surveillance

vessels to the disputed waters in what is tantamount to a “people’s war on the

high seas” has further heightened tensions. To quote commentator Sujit Dutta,

“China’s unmitigated irredentism [is] based on the . . . theory that the

periphery must be occupied in order to secure the core. [This] is an

essentially imperial notion that was internalized by the Chinese

nationalists—both Kuomintang and Communist. The [current] regime’s attempts to

reach its imagined geographical frontiers often with little historical basis

have had and continue to have highly destabilizing strategic consequences.”

One

reason Southeast Asians find it difficult to accept Chinese territorial claims

is that they carry with them an assertion of Han racial superiority over other

Asian races and empires. Says Jay Batongbacal of the University of the

Philippines law school: “Intuitively, acceptance of the nine-dash line is a

corresponding denial of the very identity and history of the ancestors of the

Vietnamese, Filipinos, and Malays; it is practically a modern revival of

China’s denigration of non-Chinese as ‘barbarians’ not entitled to equal

respect and dignity as peoples.”

Empires

and kingdoms never exercised sovereignty. If historical claims had any validity

then Mongolia could claim all of Asia simply because it once conquered the

lands of the continent. There is absolutely no historical basis to support

either of the dash-line claims, especially considering that the territories of

Chinese empires were never as carefully delimited as nation-states, but rather

existed as zones of influence tapering away from a civilized center. This is

the position contemporary China took starting in the 1960s, while negotiating

its land boundaries with several of its neighboring countries. But this is not

the position it takes today in the cartographic, diplomatic, and low-intensity

military skirmishes to define its maritime borders. The continued reinterpretation

of history to advance contemporary political, territorial, and maritime claims,

coupled with the Communist leadership’s ability to turn “nationalistic

eruptions” on and off like a tap during moments of tension with the United

States, Japan, South Korea, India, Vietnam, and the Philippines, makes it

difficult for Beijing to reassure neighbors that its “peaceful rise” is wholly

peaceful. Since there are six claimants to various atolls, islands, rocks, and

oil deposits in the South China Sea, the Spratly Islands disputes are, by

definition, multilateral disputes requiring international arbitration. But

Beijing has insisted that these disputes are bilateral in order to place its

opponents between the anvil of its revisionist history and the hammer of its

growing military power.

Mohan Malik is a professor in

Asian security at Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, in Honolulu. The

views expressed are his own. His most recent book is China and India: Great

Power Rivals. He wishes to thank Drs. Justin Nankivell, Carlyle Thayer, Denny

Roy, and David Fouse for their comments on this article.

http://www.worldaffairsjournal.org/article/historical-fiction-china%E2%80%99s-south-china-sea-claims

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

PH Justice Carpio debunks China’s historical claim

of South China Sea

By Ellen Tordesillas, Contributor

Using China’s very own ancient maps, Justice Antonio T. Carpio debunked the Asian superpower's ownership claims of almost the whole of South China Sea based on “historical facts.”

In lecture at De La Salle University "Historical Facts, Historical Lies and Historical Rights in the West Philippine Sea," Carpio took up China’s invitation to look at the “historical facts” by examining not only Chinese ancient maps but also maps of Philippine authorities and other nationalities.

Carpio said “All these ancient maps show that since the first Chinese maps appeared,the southern most territory of China has always been Hainan Island, with its ancient names being Zhuya, then Qiongya, and thereafter Qiongzhou. “

“Hainan Island was for centuries a part of Guangdong Province until 1988 when it became a separate province,” he added.

Carpio said that after the Philippines filed in January 2013 its arbitration case against China before an international tribunal, invoking UNCLOS (United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea ) to protect the Exclusive Economic Zone of the Philippines, China stressed “historical facts” as another basis for its maritime claims in the South China Sea.

Carpio said Chinese diplomats now declare that they will not give one inch of territory that their ancestors bequeathed to them.

He quoted General Fang Fenghui, Chief of Staff of the People’s Liberation Army, during his recent visit to the United States saying, “territory passed down by previous Chinese generations to the present one will not be forgotten or sacrificed.”

In lecture at De La Salle University "Historical Facts, Historical Lies and Historical Rights in the West Philippine Sea," Carpio took up China’s invitation to look at the “historical facts” by examining not only Chinese ancient maps but also maps of Philippine authorities and other nationalities.

Carpio said “All these ancient maps show that since the first Chinese maps appeared,the southern most territory of China has always been Hainan Island, with its ancient names being Zhuya, then Qiongya, and thereafter Qiongzhou. “

“Hainan Island was for centuries a part of Guangdong Province until 1988 when it became a separate province,” he added.

Carpio said that after the Philippines filed in January 2013 its arbitration case against China before an international tribunal, invoking UNCLOS (United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea ) to protect the Exclusive Economic Zone of the Philippines, China stressed “historical facts” as another basis for its maritime claims in the South China Sea.

Carpio said Chinese diplomats now declare that they will not give one inch of territory that their ancestors bequeathed to them.

He quoted General Fang Fenghui, Chief of Staff of the People’s Liberation Army, during his recent visit to the United States saying, “territory passed down by previous Chinese generations to the present one will not be forgotten or sacrificed.”

Carpio said “Historical facts, even if true, relating to discovery and exploration in the Age of Discovery (early 15th century until the 17th century) or even earlier, have no bearing whatsoever in the resolution of maritime disputes under UNCLOS. Neither Spain nor Portugal can ever revive their 15th century claims to ownership of all the oceans and seas of our planet, despite the 1481 Papal Bull confirming the division of the then undiscovered world between Spain and Portugal. The sea voyages of the Chinese Imperial Admiral Zheng He, from 1405-1433, can never be the basis of any claim to the South China Sea. Neither can historical names serve as basis for claiming the oceans and seas. The South China Sea was not even named by the Chinese but by European navigators and cartographers. The Song and Ming Dynasties called the South China Sea the “Giao Chi Sea,” and the Qing Dynasty, the Republic of China as well as the People’s Republic of China call it the “South Sea” without the word “China.” India cannot claim the Indian Ocean, and Mexico cannot claim the Gulf of Mexico, in the same way that the Philippines cannot claim thePhilippine Sea, just because historically these bodies of water have been named after these countries.”

Carpio said in the early 17th century, Hugo Grotius, the founder of international law, wrote that “the oceans and seas of our planet belonged to all mankind, and no nation could claim ownership to the oceans and seas.“

This revolutionary idea of Hugo Grotius later became the foundation of the law of the sea under international law.

To download Carpio’s complete speech please go to :

https://dl.dropboxusercontent.com/u/18010607/The%20Historical%20Facts%20in%20the%20WPS.pdf

https://ph.news.yahoo.com/blogs/the-inbox/ph-justice-carpio-debunks-china-historical-claims-south-140906288.html?.tsrc=warhol

Carpio said in the early 17th century, Hugo Grotius, the founder of international law, wrote that “the oceans and seas of our planet belonged to all mankind, and no nation could claim ownership to the oceans and seas.“

This revolutionary idea of Hugo Grotius later became the foundation of the law of the sea under international law.

To download Carpio’s complete speech please go to :

https://dl.dropboxusercontent.com/u/18010607/The%20Historical%20Facts%20in%20the%20WPS.pdf

https://ph.news.yahoo.com/blogs/the-inbox/ph-justice-carpio-debunks-china-historical-claims-south-140906288.html?.tsrc=warhol

YouTube Videos of Kalayaan Islands Group / Spratly

China Get out of Ayungin Shoal

Please read also the below related postings :

Ang Islang Kinamkam ng Tsina

http://roilogolez.blogspot.com/2013/08/south-china-sea-ang-islang-kinamkam-ng.html

Geopolitics of Scarborough Shoal

http://www.irasec.com/ouvrage34,

BRP Sierra Madre at Ayungin Shoal

http://jibraelangel2blog.blogspot.com/2014/04/ayungin-shoal-philippines-last-line-of.html

China's aggresion in Scarborough Shoal http://jibraelangel2blog.blogspot.com/2012/05/rally-against-chinas-aggresion-in.html

No comments:

Post a Comment