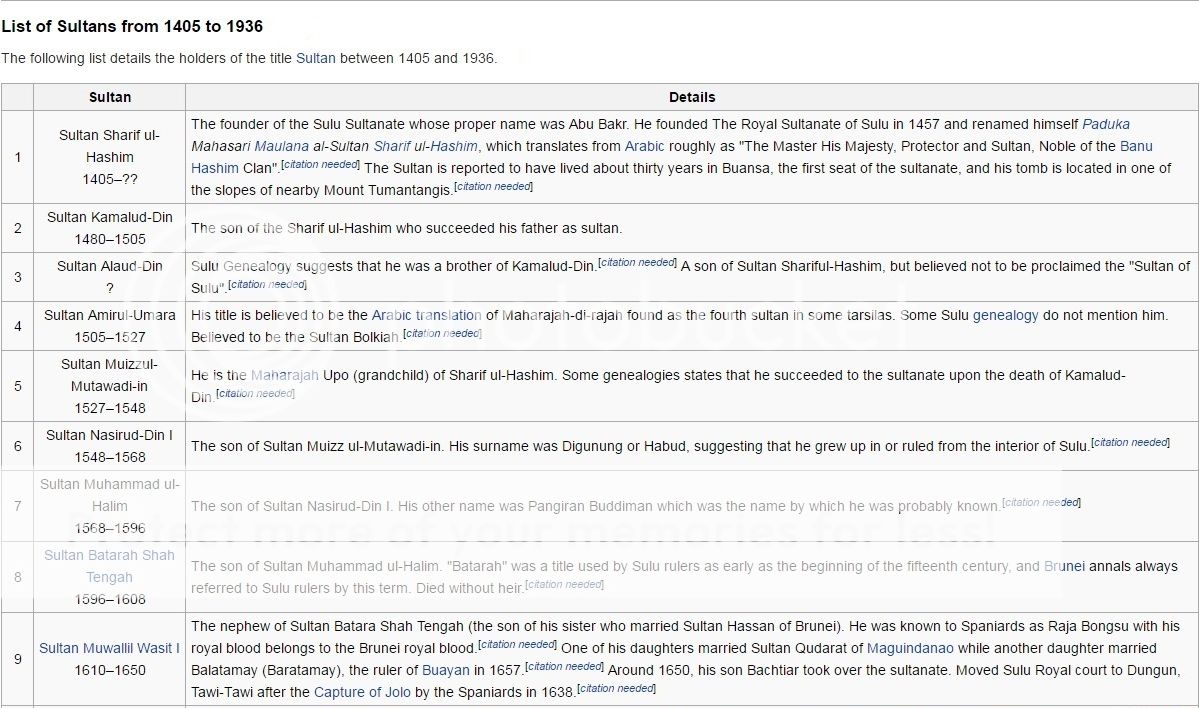

The Project Gutenberg eBook

( Chapter VII of " British Borneo " by W. H. Treacher )

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/27547/27547-h/27547-h.htm

The mode of acquisition of British North Borneo has been referred to in former pages; it was by cession for annual money payments to the Sultans of Brunai and of Sulu, who had conflicting claims to be the paramount power in the northern portion of Borneo. The actual fact was that neither of them exercised any real government or authority over by far the greater portion, the inhabitants of the coast on the various rivers following any Brunai, Illanun, Bajau, or Sulu Chief who had sufficient force of character to bring himself to the front. The pagan tribes of the interior owned allegiance to neither Sultan, and were left to govern themselves, the Muhammadan coast people considering them fair game for plunder and oppression whenever opportunity occurred, and using all their endeavours to prevent Chinese and other foreign traders from reaching them, acting themselves as middlemen, buying (bartering) at very cheap rates from the aborigines and selling for the best price they could obtain to the foreigner.

I believe I am right in saying that the idea of forming a Company, something after the manner of the East India Company, to take over and govern North Borneo, originated in the

[93]following manner. In 1865 Mr.

Moses, the unpaid Consul for the United Sates in Brunai, to whom reference has been made before, acquired with his friends from the Sultan of Brunai some concessions of territory with the right to govern and collect revenues, their idea being to introduce Chinese and establish a Colony. This they attempted to carry out on a small scale in the Kimanis River, on the West Coast, but not having sufficient capital the scheme collapsed, but the concession was retained. Mr.

Moses subsequently lost his life at sea, and a Colonel

Torrey became the chief representative of the American syndicate. He was engaged in business in China, where he met Baron

von Overbeck, a merchant of Hongkong and Austrian Consul-General, and interested him in the scheme. In 1875 the Baron visited Borneo in company with the Colonel, interviewed the Sultan of Brunai, and made enquiries as to the validity of the concessions, with apparently satisfactory results, Mr.

Alfred Dent[16] was also a China merchant well known in Shanghai, and he in turn was interested in the idea by Baron

Overbeck. Thinking there might be something in the scheme, he provided the required capital, chartered a steamer, the

America, and authorised Baron

Overbeck to proceed to Brunai to endeavour, with Colonel

Torrey's assistance, to induce the Sultan and his Ministers to transfer the American cessions to himself and the Baron, or rather to cancel the previous ones and make out new ones in their favour and that of their heirs, associates, successors and assigns for so long as they should choose or desire to hold them. Baron

von Overbeck was accompanied by Colonel

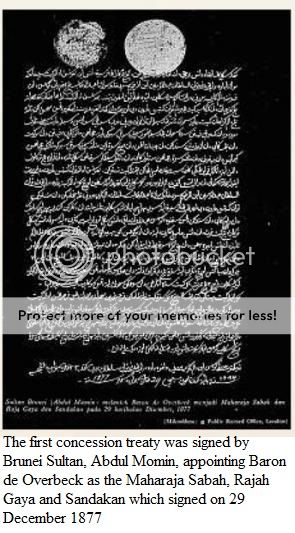

Torrey and a staff of three Europeans, and, on settling some arrears due by the American Company, succeeded in accomplishing the objects of his mission, after protracted and tedious negotiations, and obtained a "chop" from the Sultan nominating and appointing him supreme ruler, "with the title of Maharaja of Sabah (North Borneo) and Raja of Gaya and Sandakan, with power of life and death over the inhabitants, with all the absolute rights of

[94]property vested in the Sultan over the soil of the country, and the right to dispose of the same, as well as of the rights over the productions of the country, whether mineral, vegetable, or animal, with the rights of making laws, coining money, creating an army and navy, levying customs rates on home and foreign trade and shipping, and other dues and taxes on the inhabitants as to him might seem good or expedient, together with all other powers and rights usually exercised by and belonging to sovereign rulers, and which the Sultan thereby delegated to him of his own free will; and the Sultan called upon all foreign nations, with whom he had formed friendly treaties and alliances, to acknowledge the said Maharaja as the Sultan himself in the said territories and to respect his authority therein; and in the case of the death or retirement from the said office of the said Maharaja, then his duly appointed successor in the office of Supreme Ruler and Governor-in-Chief of the Company's territories in Borneo should likewise succeed to the office and title of Maharaja of Sabah and Raja of Gaya and Sandakan, and all the powers above enumerated be vested in him." I am quoting from the preamble to the Royal Charter. Some explanation of the term "Sabah" as applied to the territory—a term which appears in the Prayer Book version of the 72nd Psalm, verse 10, "The kings of Arabia and Sabah shall bring gifts"—seems called for, but I regret to say I have not been able to obtain a satisfactory one from the Brunai people, who use it in connection only with a small portion of the West Coast of Borneo, North of the Brunai river. Perhaps the following note, which I take from Mr.

W. E. Maxwell's "Manual of the Malay Language," may have some slight bearing on the point:—"Sawa, Jawa, Saba, Jaba, Zaba, etc., has evidently in all times been the capital local name in Indonesia. The whole archipelago was pressed into an island of that name by the Hindus and Romans. Even in the time of

Marco Polo we have only a Java Major and a Java Minor. The Bugis apply the name of Jawa,

jawaka (comp. the Polynesian

Sawaiki, Ceramese

Sawai) to the Moluccas. One of the principal divisions of Battaland in Sumatra is called

Tanah Jawa.

Ptolemy has both Jaba and Saba."—"Logan, Journ. Ind. Arch., iv, 338." In the Brunai use of

[95]the term, there is always some idea of a Northerly direction; for instance, I have heard a Brunai man who was passing from the South to the Northern side of his river, say he was going

Saba. When the Company's Government was first inaugurated, the territory was, in official documents, mentioned as Sabah, a name which is still current amongst the natives, to whom the now officially accepted designation of

North Borneo is meaningless and difficult of pronunciation.

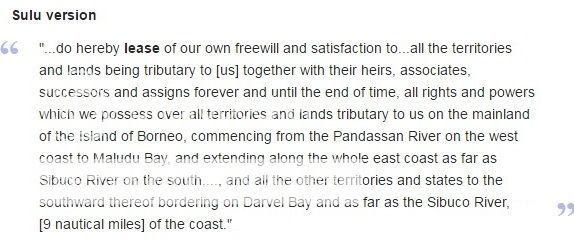

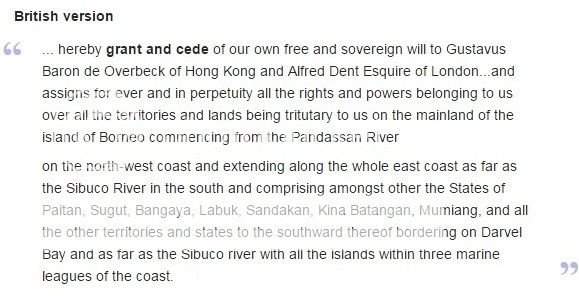

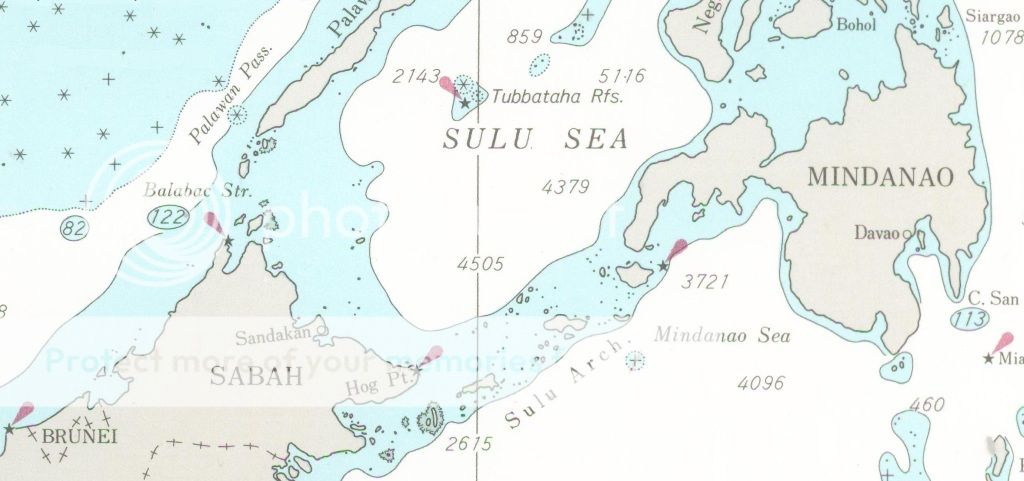

Having settled with the Brunai authorities, Baron von Overbeck next proceeded to Sulu, and found the Sultan driven out of his capital, Sugh or Jolo, by the Spaniards, with whom he was still at war, and residing at Maibun, in the principal island of the Sulu Archipelago. After brief negotiations, the Sultan made to Baron von Overbeck and Mr.Alfred Dent a grant of his rights and powers over the territories and lands tributary to him on the mainland of the island of Borneo, from the Pandassan River on the North West Coast to the Sibuko River on the East, and further invested the Baron, or his duly appointed successor in the office of supreme ruler of the Company's territories in Borneo, with the high sounding titles of Datu Bandahara and Raja of Sandakan.

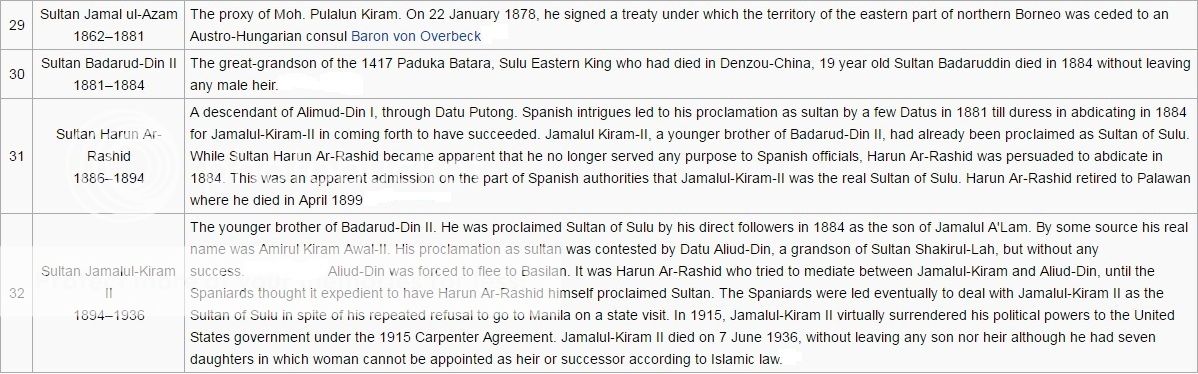

On a company being formed to work the concessions, Baron von Overbeck resigned these titles from the Brunai and Sulu Potentates and they have not since been made use of, and the Baron himself terminated his connection with the country.

The grant from the Sultan of Sulu bears date the 22nd January, 1878, and on the 22nd July of the same year he signed a treaty, or act of re-submission to Spain. The Spanish Government claimed that, by previous treaties with Sulu, the suzerainty of Spain over Sulu and its dependencies in Borneo had been recognised and that consequently the grant to Mr.

Dent was void. The British Government did not, however, fall in with this view, and in the early part of 1879, being then Acting Consul-General in Borneo, I was despatched to Sulu and to different points in North Borneo to publish, on behalf of our Government, a protest against the claim of Spain to any portion of the country. In March, 1885, a

[96]protocol was signed by which, in return for the recognition by England and Germany of Spanish sovereignty throughout the Archipelago of Sulu, Spain renounced all claims of sovereignty over territories on the Continent of Borneo which had belonged to the Sultan of Sulu, including the islands of Balambangan, Banguey and Malawali, as well as all those comprised within a zone of three maritime leagues from the coast.

Holland also strenuously objected to the cessions and to their recognition, on the ground that the general tenor of the Treaty of London of 1824 shews that a mixed occupation by England and the Netherlands of any island in the Indian Archipelago ought to be avoided.

It is impossible to discover anything in the treaty which bears out this contention. Borneo itself is not mentioned by name in the document, and the following clauses are the only ones regulating the future establishment of new Settlements in the Eastern Seas by either Power:—"Article 6. It is agreed that orders shall be given by the two Governments to their Officers and Agents in the East not to form any new Settlements on any of the islands in the Eastern Seas, without previous authority from their respective Governments in Europe. Art. 12. His Britannic Majesty, however, engages, that no British Establishment shall be made on the Carimon islands or on the islands of Battam, Bintang, Lingin, or on any of the other islands South of the Straits of Singapore, nor any treaty concluded by British authority with the chiefs of those islands." Without doubt, if Holland in 1824 had been desirous of prohibiting any British Settlement in the island of Borneo, such prohibition would have been expressed in this treaty. True, perhaps half of this great island is situated South of the Straits of Singapore, but the island cannot therefore be correctly said to lie to the South of the Straits and, at any rate, such a business-like nation as the Dutch would have noticed a weak point here and have included Borneo in the list with Battam and the other islands enumerated. Such was the view taken by Mr.

Gladstone'sCabinet, and Lord

Granville informed the Dutch Minister in 1882 that the XIIth Article of the Treaty could not be taken to apply to Borneo, and "that as a a matter of international right they would have no ground to

[97]object even to the absolute annexation of North Borneo by Great Britain," and, moreover, as pointed out by his Lordship, the British had already a settlement in Borneo, namely the island of Labuan, ceded by the Sultan of Brunai in 1845 and confirmed by him in the Treaty of 1847. The case of Raja

Brooke in Sarawak was also practically that of a British Settlement in Borneo.

Lord Granville closed the discussion by stating that the grant of the Charter does not in any way imply the assumption of sovereign rights in North Borneo, i.e., on the part of the British Government.

There the matter rested, but now that the Government is proposing

[17] to include British North Borneo, Brunai and Sarawak under a formal "British Protectorate," the Netherlands Government is again raising objections, which they must be perfectly aware are groundless. It will be noted that the Dutch do not lay any claim to North Borneo themselves, having always recognized it as pertaining, with the Sulu Archipelago, to the Spanish Crown. It is only to the presence of the British Government in North Borneo that any objection is raised. In a "Resolution" of the Minister of State, Governor-General of Netherlands India, dated 28th February, 1846, occurs the following:—"The parts of Borneo on which the Netherlands does not exercise any influence are:—

a. The States of the Sultan of Brunai or Borneo Proper;

* * * * *

b. The State of the Sultan of the Sulu Islands, having for boundaries on the West, the River Kimanis, the North and North-East Coasts as far as 3° N.L., where it is bounded by the River Atas, forming the extreme frontier towards the North with the State of Berow dependant on the Netherlands.

c. All the islands of the Northern Coasts of Borneo."

Knowing this, Mr.

Alfred Dent put the limit of his cession from Sulu at the Sibuku River, the South bank of which is in N. Lat. 4° 5'; but towards the end of 1879, that is, long

[98]after the date of the cession, the Dutch hoisted their flag at Batu Tinagat in N. Lat. 4° 19', thereby claiming the Sibuko and other rivers ceded by the Sultan of Sulu to the British Company. The dispute is still under consideration by our Foreign Office, but in September, 1883, in order to practically assert the Company's claims, I, as their Governor, had a very pleasant trip in a very small steam launch and steaming at full speed past two Dutch gun-boats at anchor, landed at the South bank of the Sibuko, temporarily hoisted the North Borneo flag, fired a

feu-de-joie, blazed a tree, and returning, exchanged visits with the Dutch gun-boats, and entertained the Dutch Controlleur at dinner. Having carefully given the Commander of one of the gun-boats the exact bearings of the blazed tree, he proceeded in hot haste to the spot, and, I believe, exterminated the said tree. The Dutch Government complained of our having violated Netherlands territory, and matters then resumed their usual course, the Dutch station at Batu Tinagat, or rather at the Tawas River, being maintained unto this day.

As is hereafter explained, the cession of coast line from the Sultan of Brunai was not a continuous one, there being breaks on the West Coast in the case of a few rivers which were not included. The annual tribute to be paid to the Sultan was fixed at $12,000, and to the Pangeran Tumonggong $3,000—extravagantly large sums when it is considered that His Highness' revenue per annum from the larger portion of the territory ceded was

nil. In March, 1881, through negotiations conducted by Mr.

A. H. Everett, these sums were reduced to more reasonable proportions, namely, $5,000 in the case of the Sultan, and $2,500 in that of the Tumonggong.

The intermediate rivers which were not included in the Sultan's cession belonged to Chiefs of the blood royal, and the Sultan was unwilling to order them to be ceded, but in 1883 Resident

Davies procured the cession from one of these Chiefs of the Pangalat River for an annual payment of $300, and subsequently the Putalan River was acquired for $1,000 per annum, and the Kawang River and the Mantanani Islands for lump sums of $1,300 and $350 respectively. In 1884, after prolonged negotiations, I was also enabled to obtain the

[99]cession of an important Province on the West Coast, to the South of the original boundary, to which the name of Dent Province has been given, and which includes the Padas and Kalias Rivers, and in the same deed of cession were also included two rivers which had been excepted in the first grant—the Tawaran and the Bangawan. The annual tribute under this cession is $3,100. The principal rivers within the Company's boundaries still unleased are the Kwala Lama, Membakut, Inanam and Menkabong. For fiscal reasons, and for the better prevention of the smuggling of arms and ammunition for sale to head-hunting tribes, it is very desirable that the Government of these remaining independent rivers should be acquired by the Company.

On the completion of the negotiations with the two Sultans, Baron

von Overbeck, who was shortly afterwards joined by Mr.

Dent, hoisted his flag—the house flag of Mr.

Dent'sfirm—at Sandakan, on the East Coast, and at Tampassuk and Pappar on the West, leaving at each a European, with a few so-called Police to represent the new Government, agents from the Sultans of Sulu and Brunai accompanying him to notify to the people that the supreme power had been transferred to Europeans. The common people heard the announcement with their usual apathy, but the officer left in charge had a difficult part to play with the headmen who, in the absence of any strong central Government, had practically usurped the functions of Government in many of the rivers. These Chiefs feared, and with reason, that not only would their importance vanish, but that trade with the inland tribes would be thrown open to all, and slave dealing be put a stop to under the new regime. At Sandakan, the Sultan's former Governor refused to recognise the changed position of affairs, but he had a resolute man to deal with in Mr.

W. B. Pryer, and before he could do much harm, he lost his life by the capsizing of his prahu while on a trading voyage.

At Tampassuk, Mr.

Pretyman, the Resident, had a very uncomfortable post, being in the midst of lawless, cattle-lifting and slave-dealing Bajaus and Illanuns. He, with the able assistance of Mr. F. X.

Witti, an ex-Naval officer of the

[100]Austrian Service, who subsequently lost his life while exploring in the interior, and by balancing one tribe against another, managed to retain his position without coming to blows, and, on his relinquishing the service a few months afterwards, the arduous task of representing the Government without the command of any force to back up his authority developed on Mr.

Witti. In the case of the Pappar River, the former Chief, Datu

Bahar, declined to relinquish his position, and assumed a very defiant attitude. I was at that time in the Labuan service, and I remember proceeding to Pappar in an English man-of-war, in consequence of the disquieting rumours which had reached us, and finding the Resident, Mr.

A. H. Everett, on one side of the small river with his house strongly blockaded and guns mounted in all available positions, and the Datu on the other side of the stream, immediately opposite to him, similarly armed to the teeth. But not a shot was fired, and Datu

Bahar is now a peaceable subject of the Company.

The most difficult problem, however, which these officers had to solve was that of keeping order, or trying to do so, amongst a lawless people, with whom for years past might had been right, and who considered kidnapping and cattle-lifting the occupations of honourable and high spirited gentlemen. That they effected what they did, that they kept the new flag flying and prepared the way for the Government of the Company, reflects the highest credit upon their pluck and diplomatic ingenuity, for they had neither police nor steam launches, nor the prestige which would have attached to them had they been representatives of the British Government, and under the well known British flag. They commenced their work with none of the

éclat which surrounded Sir

James Brooke in Sarawak, where he found the people in successful rebellion against the Sultan of Brunai, and was himself recognised as an agent of the British Government, so powerful that he could get the Queen's ships to attack the head hunting pirates, killing such numbers of them that, as I have said, the Head money claimed and awarded by the British Government reached the sum of £20,000. On the other hand, it is but fair to add that the fame of Sir

James' exploits and the

[101]action taken by Her Majesty's vessels, on his advice, in North-West Borneo years before, had inspired the natives with a feeling of respect for Englishmen which must have been a powerful factor in favour of the newly appointed officers. The native tribes, too, inhabiting North Borneo were more sub-divided, less warlike, and less powerful than those of Sarawak.

The promoters of the scheme were fortunate in obtaining the services, for the time being, as their chief representative in the East of Mr. W. H. Read, C.M.G., an old friend of SirJames Brooke, and who, as a Member of the Legislative Council of Singapore, and Consul-General for the Netherlands, had acquired an intimate knowledge of the Malay character and of the resources, capabilities and needs of Malayan countries.

On his return to England, Mr. Dent found that, owing to the opposition of the Dutch and Spanish Governments, and to the time required for a full consideration of the subject by Her Majesty's Ministers, there would be a considerable delay before a Royal Charter could be issued, meanwhile, the expenditure of the embryo Government in Borneo was not inconsiderable, and it was determined to form a "Provisional Association" to carry on till a Chartered Company could be formed.

Mr. Dent found an able supporter in Sir Rutherford Alcock, K.C.B., who energetically advocated the scheme from patriotic motives, recognising the strategic and commercial advantages of the splendid harbours of North Borneo and the probability of the country becoming in the near future a not unimportant outlet for English commerce, now so heavily weighted by prohibitive tariffs in Europe and America.

The British North Borneo Provisional Association Limited, was formed in 1881, with a capital of £300,000, the Directors being Sir

Rutherford Alcock, Mr.

A. Dent, Mr.

R. B. Martin, Admiral

Mayne, and Mr.

W. H. Read. The Association acquired from the original lessees the grants and commissions from the Sultans, with the object of disposing of these territories, lands and property to a Company to be incorporated by Royal Charter. This Charter passed the Great

[102]Seal on the 1st November, 1881, and constituted and incorporated the gentlemen above-mentioned as "The British North Borneo Company."

The Provisional Association was dissolved, and the Chartered Company started on its career in May, 1882. The nominal capital was two million pounds, in £20 shares, but the number of shares issued, including 4,500 fully paid ones representing £90,000 to the vendors, was only 33,030, equal to £660,600, but on 23,449 of these shares only £12 have so far been called up. The actual cash, therefore, which the Company has had to work with and to carry on the development of the country from the point at which the original concessionaires and the Provisional Association had left it, is, including some £1,000 received for shares forfeited, about £384,000, and they have a right of call for £187,592 more. The Charter gave official recognition to the concessions from the Native Princes, conferred extensive powers on the Company as a corporate body, provided for the just government of the natives and for the gradual abolition of slavery, and reserved to the Crown the right of disapproving of the person selected by the Company to be their Governor in the East, and of controlling the Company's dealings with any Foreign Power.

The Charter also authorised the Company to use a distinctive flag, indicating the British character of the undertaking, and the one adopted, following the example of the English Colonies, is the British flag, "defaced," as it is termed, with the Company's badge—a lion. I have little doubt that this selection of the British flag, in lieu of the one originally made use of, had a considerable effect in imbuing the natives with an idea of the stability and permanence of the Company's Government.

Mr.

Dent's house flag was unknown to them before and, on the West Coast, many thought that the Company's presence in the country might be only a brief one, like that of its predecessor, the American syndicate, and, consequently, were afraid to tender their allegiance, since, on the Company's withdrawal, they would be left to the tender mercies of their former Chiefs. But the British flag was well-known to those of them who were traders, and they had seen it flying

[103]for many a year in the Colony of Labuan and on board the vessels which had punished their piratical acts in former days.

Then, too, I was soon able to organise a Police Force mainly composed of Sikhs, and was provided with a couple of steam-launches. Owing doubtless to that and other causes, the refractory chiefs, soon after the Company's formation, appeared to recognize that the game of opposition to the new order of things was a hopeless one.

Chapter VIII.

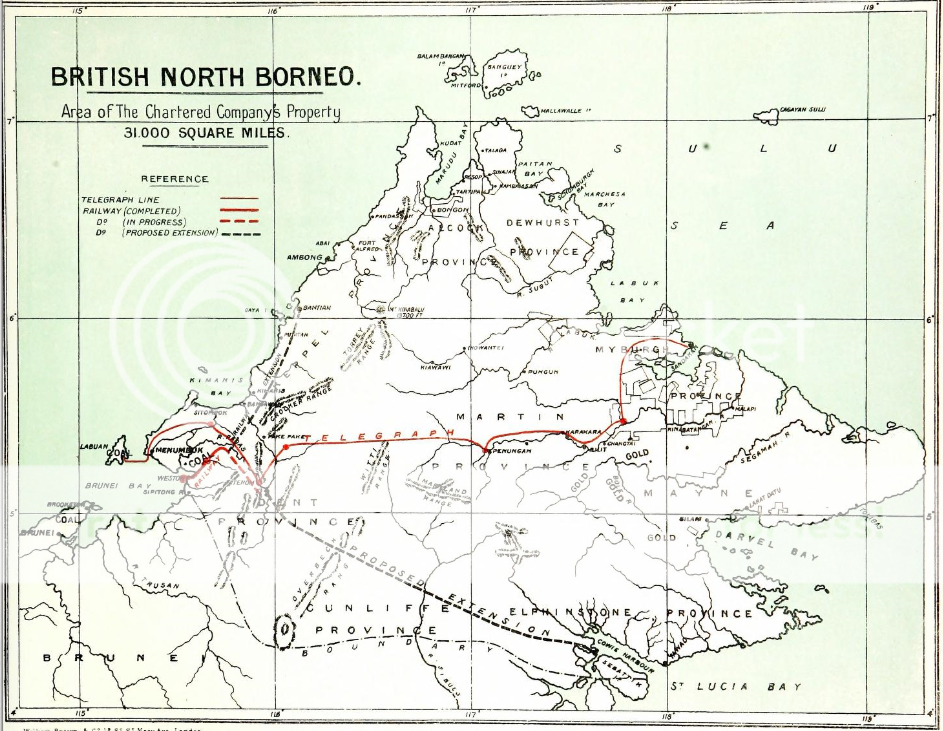

The area of the territory ceded by the original grants was estimated at 20,000 square miles, but the additions which have been already mentioned now bring it up to about 31,000 square miles, including adjacent islands, so that it is somewhat larger than Ceylon, which is credited with only 25,365 square miles. In range of latitude, in temperature and in rainfall, North Borneo presents many points of resemblance to Ceylon, and it was at first thought that it might be possible to attract to the new country some of the surplus capital, energy and aptitude for planting which had been the foundation of Ceylon's prosperity.

Even the expression "The New Ceylon" was employed as an alternative designation for the country, and a description of it under that title was published by the well known writer—Mr. Joseph Hatton.

These hopes have not so far been realized, but on the other hand North Borneo is rapidly becoming a second Sumatra, Dutchmen, Germans and some English having discovered the suitability of its soil and climate for producing tobacco of a quality fully equal to the famed Deli leaf of that island.

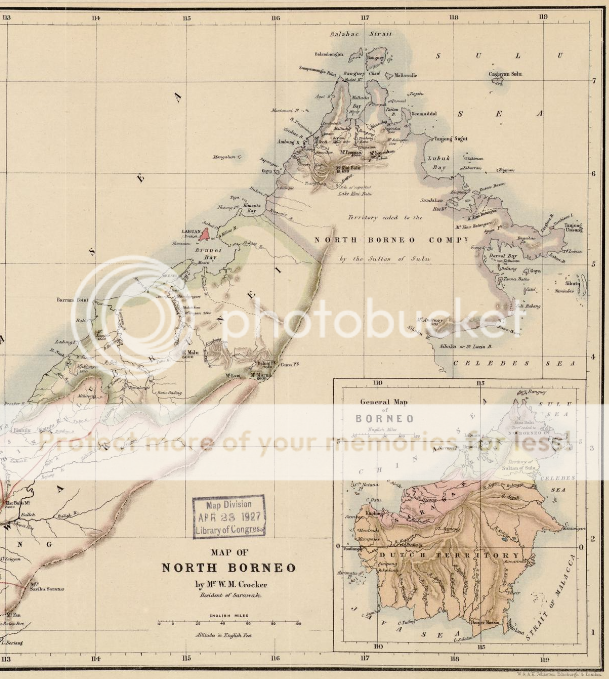

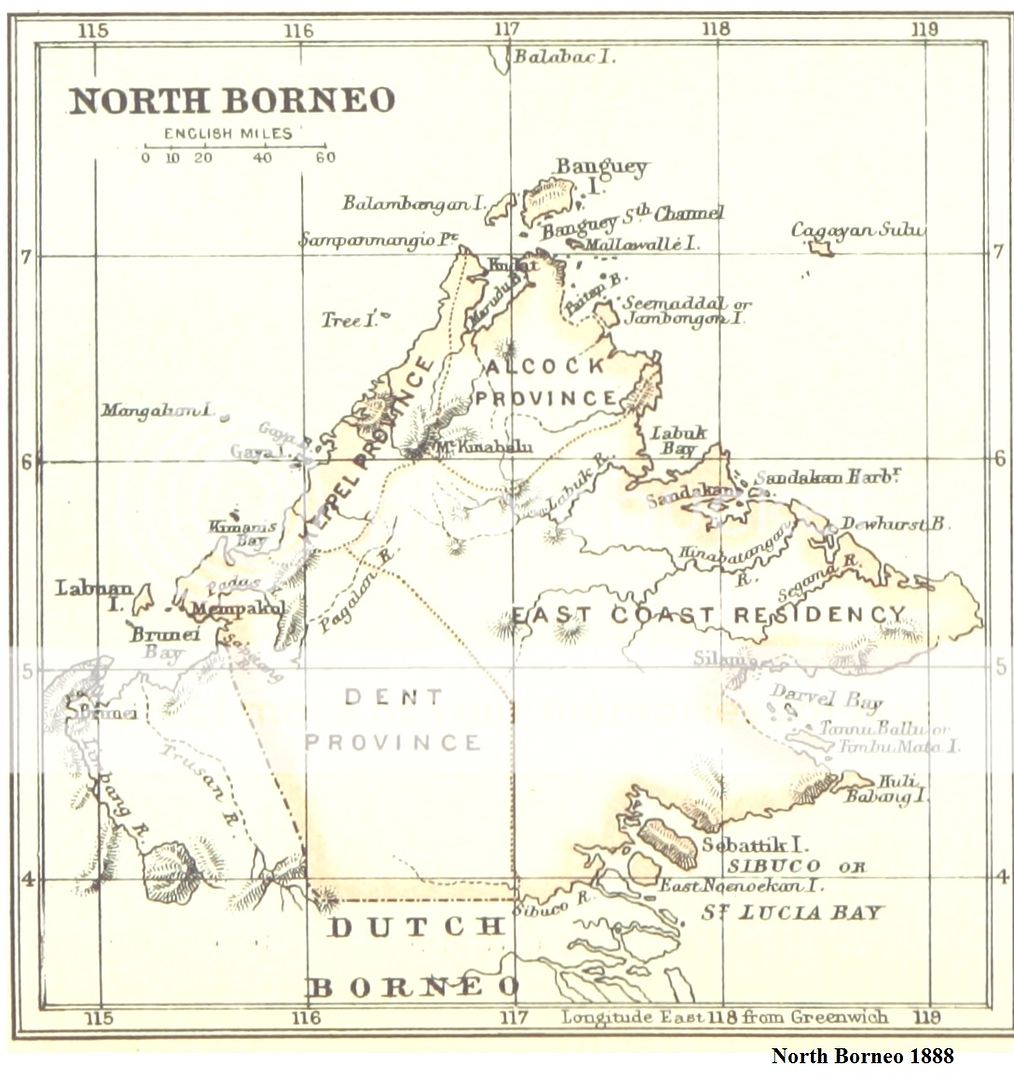

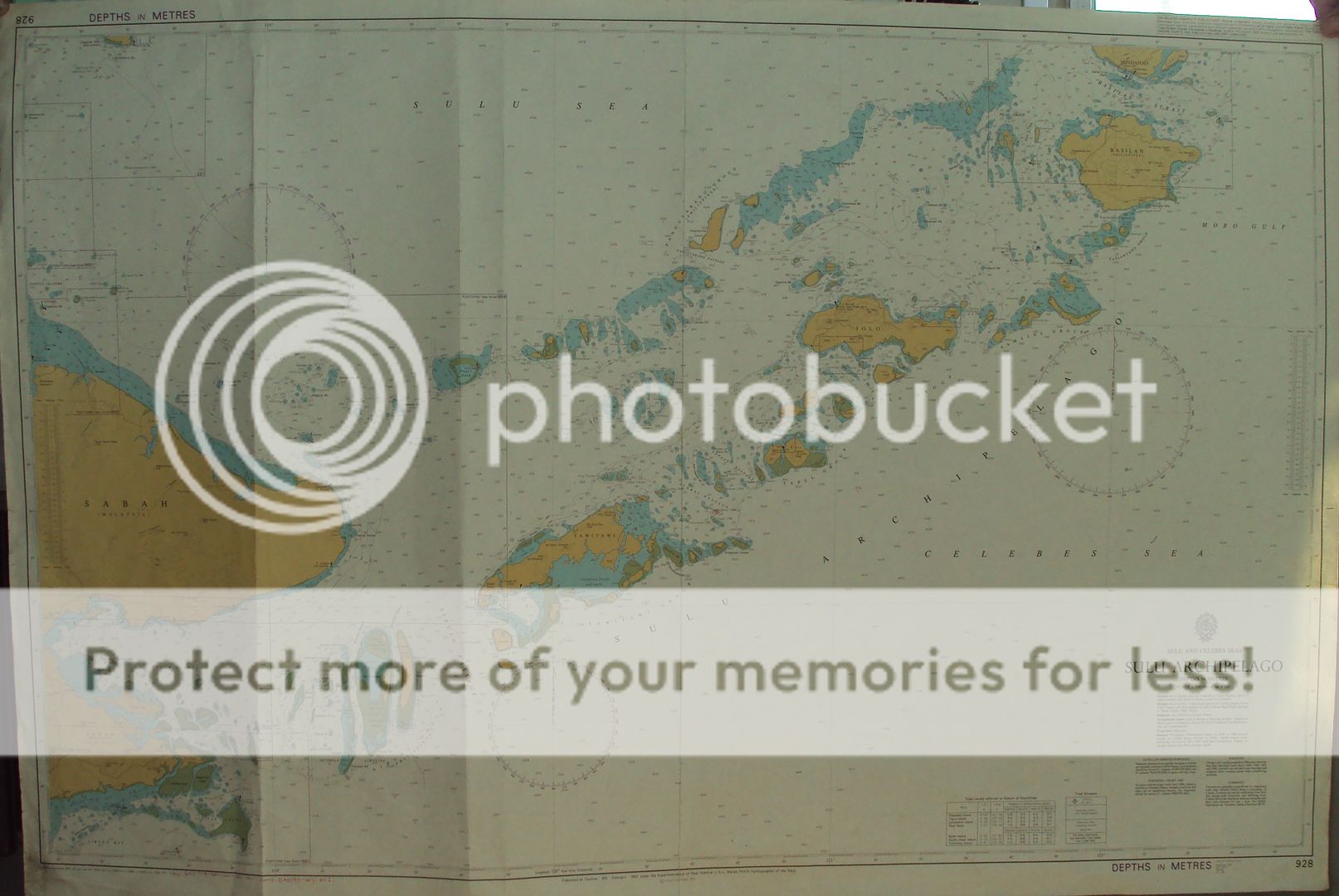

The coast line of the territory is about one thousand miles, and a glance at the map will shew that it is furnished with capital harbours, of which the principal are Gaya Bay on the West, Kudat in Marudu Bay on the North, and Sandakan Harbour on the East. There are several others, but at those enumerated the Company have opened their principal stations.

[104]Of the three mentioned, the more striking is that of Sandakan, which is 15 miles in length, with a width varying from 11 miles, at its entrance, to 5 miles at the broadest part. It is here that the present capital is situated—Sandakan, a town containing a population of not more than 5,000 people, of whom perhaps thirty are Europeans and a thousand Chinese., For its age, Sandakan has suffered serious vicissitudes. It was founded by Mr.

Pryer, in 1878, well up the bay, but was soon afterwards burnt to the ground. It was then transferred to its present position, nearer the mouth of the harbour, but in May, 1886, the whole of what was known as the "Old Town" was utterly consumed by fire; in about a couple of hours there being nothing left of the

atap-built shops and houses but the charred piles and posts on which they had been raised above the ground. When a fire has once laid hold of an atap town, probably no exertions would much avail to check it; certainly our Chinese held this opinion, and it was impossible to get them to move hand or foot in assisting the Europeans and Police in their efforts to confine its ravages to as limited an area as possible. They entertain the idea that such futile efforts tend only to aggravate the evil spirits and increase their fury. The Hindu shopkeepers were successful in saving their quarter of the town by means of looking glasses, long prayers and chants. It is now forbidden to any one to erect atap houses in the town, except in one specified area to which such structures are confined. Most of the present houses are of plank, with tile, or corrugated iron roofs, and the majority of the shops are built over the sea, on substantial wooden piles, some of the principal "streets," including that to which the ambitious name of "The Praya" has been given, being similarly constructed on piles raised three or four feet above high water mark. The reason is that, owing to the steep hills at the back of the site, there is little available flat land for building on, and, moreover, the pushing Chinese trader always likes to get his shops as near as possible to the sea—the highway of the "prahus" which bring him the products of the neighbouring rivers and islands. In time, no doubt, the Sandakan hills will be used to reclaim more land from the sea, and the town will cease to

[105]be an amphibious one. In the East there are, from a sanitary point of view, some points of advantage in having a tide-way passing under the houses. I should add that Sandakan is a creation of the Company's and not a native town taken over by them. When Mr.

Pryer first hoisted his flag, there was only one solitary Chinaman and no Europeans in the harbour, though at one time, during the Spanish blockade of Sulu, a Singapore firm had established a trading station, known as "Kampong German," using it as their head-quarters from which to run the blockade of Sulu, which they successfully did for some considerable time, to their no small gain and advantage. The success attending the Germans' venture excited the emulation of the Chinese traders of Labuan, who found their valuable Sulu trade cut off and, through the good offices of the Government of the Colony, they were enabled to charter the Sultan of Brunai's smart little yacht the

Sultana, and engaging the services as Captain of an ex-member of the Labuan Legislative Council, they endeavoured to enact the roll of blockade runner. After a trip or two, however, the

Sultana was taken by the Spaniards, snugly at anchor in a Sulu harbour, the Captain and Crew having time to make their escape. As she was not under the British flag, the poor Sultan could obtain no redress, although the blockade was not recognised as effective by the European Powers and English and German vessels, similarly seized, had been restored to their owners. The

Sultana proved a convenient despatch boat for the Spanish authorities. The Sultan of Sulu to prove his friendship to the Labuan traders, had an unfortunate man cut to pieces with krisses, on the charge of having betrayed the vessel's position to the blockading cruisers.

Sandakan is one of the few places in Borneo which has been opened and settled without much fever and sickness ensuing, and this was due chiefly to the soil being poor and sandy and to there being an abundance of good, fresh, spring water. It may be stated, as a general rule, that the richer the soil the more deadly will be the fever the pioneers will have to encounter when the primeval jungle is first felled and the sun's rays admitted to the virgin soil.

[106]Sandakan is the principal trading station in the Company's territory, but with Hongkong only 1,200 miles distant in one direction, Manila 600 miles in another, and Singapore 1,000 miles in a third, North Borneo can never become an emporium for the trade of the surrounding countries and islands, and the Court of Directors must rest content with developing their own local trade and pushing forward, by wise and encouraging regulations, the planting interest, which seems to have already taken firm root in the country and which will prove to be the foundation of its future prosperity. Gold and other minerals, including coal, are known to exist, but the mineralogical exploration of a country covered with forest and destitute of roads is a work requiring time, and we are not yet in a position to pronounce on North Borneo's expectations in regard to its mineral wealth.

The gold on the Segama River, on the East coast, has been several times reported on, and has been proved to exist in sufficient quantities to, at any rate, well repay the labours of Chinese gold diggers, but the district is difficult of access by water, and the Chinese are deferring operations on a large scale until the Government has constructed a road into the district. A European Company has obtained mineral concessions on the river, but has not yet decided on its mode of operation, and individual European diggers have tried their luck on the fields, hitherto without meeting with much success, owing to heavy rains, sickness and the difficulty of getting up stores. The Company will probably find that Chinese diggers will not only stand the climate better, but will be more easily governed, be satisfied with smaller returns, and contribute as much or more than the Europeans to the Government Treasury, by their consumption of opium, tobacco and other excisable articles, by fees for gold licenses, and so forth.

Another source of natural wealth lies in the virgin forest with which the greater portion of the country is clothed, down to the water's edge. Many of the trees are valuable as timber, especially the

Billian, or Borneo iron-wood tree, which is impervious to the attacks of white-ants ashore and almost equally so to those of the

teredo navalis afloat, and is wonderfully enduring of exposure to the tropical sun and the tropical

[107]downpours of rain. I do not remember having ever come across a bit of

billian that showed signs of decay during a residence of seventeen years in the East. The wood is very heavy and sinks in water, so that, in order to be shipped, it has to be floated on rafts of soft wood, of which there is an abundance of excellent quality, of which one kind—the red

serayah—is likely to come into demand by builders in England. Other of the woods, such as

mirabau,

penagah and

rengas, have good grain and take a fine polish, causing them to be suitable for the manufacture of furniture. The large tree which yields the Camphor

barus of commerce also affords good timber. It is a

Dryobalanops, and is not to be confused with the

Cinnamomum camphora, from which the ordinary "camphor" is obtained and the wood of which retains the camphor smell and is largely used by the Chinese in the manufacture of boxes, the scented wood keeping off ants and other insects which are a pest in the Far East. The Borneo camphor tree is found only in Borneo and Sumatra. The camphor which is collected for export, principally to China and India, by the natives, is found in a solid state in the trunk, but only in a small percentage of the trees, which are felled by the collectors. The price of this camphor

barus as it is termed, is said to be nearly a hundred times as much as that of the ordinary camphor, and it is used by the Chinese and Indians principally for embalming purposes. Billian and other woods enumerated are all found near the coast and, generally, in convenient proximity to some stream, and so easily available for export. Sandakan harbour has some thirteen rivers and streams running into it, and, as the native population is very small, the jungle has been scarcely touched, and no better locality could, therefore, be desired by a timber merchant. Two European Timber Companies are now doing a good business there, and the Chinese also take their share of the trade. China affords a ready and large market for Borneo timber, being itself almost forestless, and for many years past it has received iron-wood from Sarawak. Borneo timber has also been exported to the Straits Settlements, Australia and Mauritius, and I hear that an order has been given for England. Iron wood is only found in certain districts, notably in Sandakan Bay and on

[108]the East coast, being rarely met with on the West coast. I have seen a private letter from an officer in command of a British man-of-war who had some samples of it on board which came in very usefully when certain bearings of the screw shaft were giving out on a long voyage, and were found to last

three times as long as lignum vitæ.

In process of time, as the country is opened up by roads and railways, doubtless many other valuable kinds of timber trees will be brought to light in the interior.

A notice of Borneo Forests would be incomplete without a reference to the mangroves, which are such a prominent feature of the country as one approaches it by sea, lining much of the coast and forming, for mile after mile, the actual banks of most of the rivers. Its thick, dark-green, never changing foliage helps to give the new comer that general impression of dull monotony in tropical scenery, which, perhaps, no one, except the professed botanist, whose trained and practical eye never misses the smallest detail, ever quite shakes off.

The wood of the mangrove forms most excellent firewood, and is often used by small steamers as an economical fuel in lieu of coal, and is exported to China in the timber ships. The bark is also a separate article of export, being used as a dye and for tanning, and is said to contain nearly 42% of tannin.

The value of the general exports from the territory is increasing every year, having been $145,444 in 1881 and $525,879 in 1888. With the exception of tobacco and pepper, the list is almost entirely made up of the natural raw products of the land and sea—such as bees-wax, camphor, damar, gutta percha, the sap of a large forest tree destroyed in the process of collection of gutta, India rubber, from a creeper likewise destroyed by the collectors, rattans, well known to every school boy, sago, timber, edible birds'-nests, seed-pearls, Mother-o'-pearl shells in small quantities, dried fish and dried sharks'-fins, trepang (sea-slug or bêche-de-mer), aga, or edible sea-weed, tobacco (both Native and European grown), pepper, and occasionally elephants' tusks—a list which shews the country to be a rich store house of natural productions, and one which will be added to, as the land is brought under cultivation with coffee,

[109]tea, sugar, cocoa, Manila hemp, pine apple fibre, and other tropical products for which the soil, and especially the rainfall, temperature and climatic conditions generally, including entire freedom from typhoons and earthquakes, eminently adapt it, and many of which have already been tried with success on an experimental scale. As regards pepper, it has been previously shewn that North Borneo was in former days an exporter of this spice. Sugar has been grown by the natives for their own consumption for many years, as also tapioca, rice and Indian corn. It is not my object to give a detailed list of the productions of the country, and I would refer any reader who is anxious to be further enlightened on these and kindred topics to the excellent "Hand-book of British North Borneo," prepared for the Colonial and Indian Exhibition of 1886, at which the new Colony was represented, and published by Messrs.

William Clowes & Sons.

The edible birds'-nests are already a source of considerable revenue to the Government, who let out the collection of them for annual payments, and also levy an export duty as they leave the country for China, which is their only market. The nests are about the size of those of the ordinary swallow and are formed by innumerable hosts of swifts—Collocalia fuciphaga—entirely from a secretion of the glands of the throat. These swifts build in caves, some of which are of very large dimensions, and there are known to be some sixteen of them in different parts of British North Borneo. With only one exception, the caves occur in limestone rocks and, generally, at no great distance from the sea, though some have been discovered in the interior, on the banks of the Kinabatangan River. The exception above referred to is that of a small cave on a sand-stone island at the entrance of Sandakan harbour. The Collocalia fuciphaga appears to be pretty well distributed over the Malayan islands, but of these, Borneo and Java are the principal sources of supply. Nests are also exported from the Andaman Islands, and a revenue of £30,000 a year is said to be derived from the nests in the small islands in the inland sea of Tab Sab, inhabited by natives of Malay stock.

The finest caves, or rather series of caves, as yet known in the Company's territories are those of Gomanton, a limestone

[110]hill situated at the head of the Sapa Gaia, one of the streams running into Sandakan harbour.

These grand caves, which are one of the most interesting sights in the country, are, in fine weather, easily accessible from the town of Sandakan, by a water journey across the harbour and up the Sapa Gaia, of about twelve miles, and by a road from the point of debarkation to the entrance of the lower caves, about eight miles in length.

The height of the hill is estimated at 1,000 feet, and it contains two distinct series of caves. The first series is on the "ground floor" and is known as

Simud Hitam, or "black entrance." The magnificent porch, 250 feet high and 100 broad, which gives admittance to this series, is on a level with the river bank, and, on entering, you find yourself in a spacious and lofty chamber well lighted from above by a large open space, through which can be seen the entrance to the upper set of caves, some 400 to 500 feet up the hill side. In this chamber is a large deposit of guano, formed principally by the myriads of bats inhabiting the caves in joint occupancy with the edible-nest-forming swifts. Passing through this first chamber and turning a little to the right you come to a porch leading into an extensive cave, which extends under the upper series. This cave is filled half way up to its roof, with an enormous deposit of guano, which has been estimated to be 40 to 50 feet in depth. How far the cave extends has not been ascertained, as its exploration, until some of the deposit is removed, would not be an easy task, for the explorer would be compelled to walk along on the top of the guano, which in some places is so soft that you sink in it almost up to your waist. My friend Mr.

C. A. Bampfylde, in whose company I first visited Gomanton, and who, as "Commissioner of Birds-nest Caves," drew up a very interesting report on them, informed me that, though he had found it impossible to explore right to the end, he had been a long way in and was confident that the cave was of very large size. To reach the upper series of caves, you leave Simud Hitam and clamber up the hill side—a steep but not difficult climb, as the jagged limestone affords sure footing. The entrance to this series, known as

Simud Putih, or "white entrance," is estimated to be at an

[111]elevation of 300 feet above sea level, and the porch by which you enter them is about 30 feet high by about 50 wide. The floor slopes steeply downwards and brings you into an enormous cave, with smaller ones leading off it, all known to the nest collectors by their different native names. You soon come to a large black hole, which has never been explored, but which is said to communicate with the large guano cave below, which has been already described. Passing on, you enter a dome-like cave, the height of the roof or ceiling of which has been estimated at 800 feet, but for the accuracy of this guess I cannot vouch. The average height of the cave before the domed portion is reached is supposed to be about 150 feet, and Mr.

Bampfylde estimates the total length, from the entrance to the furthest point, at a fifth of a mile. The Simud Putih series are badly lighted, there being only a few "holes" in the roof of the dome, so that torches or lights of some kind are required. There are large deposits of guano in these caves also, which could be easily worked by lowering quantities down into the Simud Hitam caves below, the floor of which, as already stated, is on a level with the river bank, so that a tramway could be laid right into them and the guano be carried down to the port of shipment, at the mouth of the Sapa Gaia River. Samples of the guano have been sent home, and have been analysed by Messrs.

Voelcker & Co. It is rich in ammonia and nitrogen and has been valued at £5 to £7 a ton in England. The bat-guano is said to be richer as a manure than that derived from the swifts. To ascend to the top of Gomanton, one has to emerge from the Simud Putih entrance and, by means of a ladder, reach an overhanging ledge, whence a not very difficult climb brings one to the cleared summit, from which a fine view of the surrounding country is obtained, including Kina-balu, the sacred mountain of North Borneo. On this summit will be found the holes already described as helping to somewhat lighten the darkness of the dome-shaped cave, on the roof of which we are in fact now standing. It is through these holes that the natives lower themselves into the caves, by means of rattan ladders and, in a most marvellous manner, gain a footing on the ceiling and construct cane stages, by means of which they can reach any part of the roof

[112]and, either by hand or by a suitable pole to the end of which is attached a lighted candle, secure the wealth-giving luxury for the epicures of China. There are two principal seasons for collecting the nests, and care has to be taken that the collection is made punctually at the proper time, before the eggs are all hatched, otherwise the nests become dirty and fouled with feathers, &c., and discoloured and injured by the damp, thereby losing much of their market value. Again, if the nests are not collected for a season, the birds do not build many new ones in the following season, but make use of the old ones, which thereby become comparatively valueless.

There are, roughly speaking, three qualities of nests, sufficiently described by their names—white, red, and black—the best quality of each fetching, at Sandakan, per catty of 11⁄3 lbs., $16, $7 and 8 cents respectively.

The question as to the true cause of the difference in the nests has not yet been satisfactorily solved. Some allege that the red and black nests are simply white ones deteriorated by not having been collected in due season. I myself incline to agree with the natives that the nests are formed by different birds, for the fact that, in one set of caves, black nests are always found together in one part, and white ones in another, though both are collected with equal care and punctuality, seems almost inexplicable under the first theory. It is true that the different kinds of nests are not found in the same season, and it is just possible that the red and black nests may be the second efforts at building made by the swifts after the collectors have disturbed them by gathering their first, white ones. In the inferior nests, feathers are found mixed up with the gelatinous matter forming the walls, as though the glands were unable to secrete a sufficient quantity of material, and the bird had to eke it out with its own feathers. In the substance of the white nests no feathers are found.

Then, again, it is sometimes found in the case of two distinct caves, situated at no great distance apart, that the one yields almost entirely white nests, and the other nearly all red, or black ones, though the collections are made with equal regularity in each. The natives, as I have said, seem to think that there are two kinds of birds, and the Hon.

R.[113]Abercromby reports that, when he visited Gomanton, they shewed him eggs of different size and explained that one was laid by the white-nest bird and the other by the black-nest builder. Sir

Hugh Low, in his work on Sarawak, published in 1848, asserts that there are "two different and quite dissimilar kinds of birds, though both are swallows" (he should have said swifts), and that the one which produces the white nest is larger and of more lively colours, with a white belly, and is found on the sea-coast, while the other is smaller and darker and found more in the interior. He admits, however, that though he had opportunities of observing the former, he had not been able to procure a specimen.

The question is one which should be easily settled on the spot, and I recommend it to the consideration of the authorities of the British North Borneo Museum, which has been established at Sandakan.

The annual value of the nests of Gomanton, when properly collected, has been reckoned at $23,000, but I consider this an excessive estimate. My friend Mr. A. Cook, the Treasurer of the Territory, to whose zeal and perseverance the Company owes much, has arranged with the Buludupih tribe to collect these nests on payment to the Government of a royalty of $7,500 per annum, which is in addition to the export duty at the rate of 10% ad valorem paid by the Chinese exporters.

The swifts and bats—the latter about the size of the ordinary English bat—avail themselves of the shelter afforded by the caves without incommoding one another, for, by a sort of Box and Cox arrangement, the former occupy the caves during the night and the latter by day.

Standing at the Simud Putih entrance about 5

P. M., the visitor will suddenly hear a whirring sound from below, which is caused by the myriads of bats issuing, for their nocturnal banquet, from the Simud Itam caves, through the wide open space that has been described. They come out in a regularly ascending continuous spiral or corkscrew coil, revolving from left to right in a very rapid and regular manner. When the top of the spiral coil reaches a certain height, a colony of bats breaks off, and continuing to revolve in a well kept ring from left to right gradually ascends higher and higher, until all of

[114]a sudden the whole detachment dashes off in the direction of the sea, towards the mangrove swamps and the

nipas. Sometimes these detached colonies reverse the direction of their revolutions after leaving the main body, and, instead of from left to right, revolve from right to left. Some of them continue for a long time revolving in a circle, and attain a great height before darting off in quest of food, while others make up their minds more expeditiously, after a few revolutions. Amongst the bats, three white ones were, on the occasion of my visit, very conspicuous, and our followers styled them the Raja, his wife and child. Hawks and sea-eagles are quickly attracted to the spot, but only hover on the outskirts of the revolving coil, occasionally snapping up a prize. I also noticed several hornbills, but they appeared to have been only attracted by curiosity. Mr.

Bampfylde informed me that, on a previous visit, he had seen a large green snake settled on an overhanging branch near which the bats passed and that occasionally he managed to secure a victim. I timed the bats and found that they took almost exactly fifty minutes to come out of the caves, a thick stream of them issuing all that time and at a great pace, and the reader can endeavour to form for himself some idea of their vast numbers. They had all got out by ten minutes to six in the evening, and at about six o'clock the swifts began to come home to roost. They came in in detached, independent parties, and I found it impossible to time them, as some of them kept very late hours. I slept in the Simud Putih cave on this occasion, and found that next morning the bats returned about 5

A.M., and that the swifts went out an hour afterwards.

As shewing the mode of formation of these caves, I may add that I noticed, imbedded in a boulder of rock in the upper caves, two pieces of coral and several fossil marine shells, bivalves and others.

The noise made by the bats going out for their evening promenade resembled a combination of that of the surf breaking on a distant shore and of steam being gently blown off from a vessel which has just come to anchor.

There are other interesting series of caves, and one—that of Madai, in Darvel Bay on the East coast—was

[115]visited by the late Lady

Brassey and Miss

Brassey in April, 1887, when British North Borneo was honoured by a visit of the celebrated yacht the

Sunbeam, with Lord

Brassey and his family on board.

I accompanied the party on the trip to Madai, and shall not easily forget the pluck and energy with which Lady Brassey, then in bad health, surmounted the difficulties of the jungle track, and insisted upon seeing all that was to be seen; or the gallant style in which Miss Brassey unwearied after her long tramp through the forest, led the way over the slippery boulders in the dark caves.

The Chinese ascribe great strengthening powers to the soup made of the birds'-nests, which they boil down into a syrup with barley sugar, and sip out of tea cups. The gelatinous looking material of which the substance of the nests is composed is in itself almost flavourless.

It is also with the object of increasing their bodily powers that these epicures consume the uninviting sea-slug or bêche-de-mer, and dried sharks'-fins and cuttle fish.

To conclude my brief sketch of Sandakan Harbour and of the Capital, it should be stated that, in addition to being within easy distance of Hongkong, it lies but little off the usual route of vessels proceeding from China to Australian ports, and can be reached by half a day's deviation of the ordinary track.

Should, unfortunately, war arise with Russia, there is little doubt their East Asiatic squadron would endeavour both to harass the Australian trade and to damage, as much as possible, the coast towns, in which case the advantages of Sandakan, midway between China and Australia, as a base of operations for the British protecting fleet would at once become manifest. It is somewhat unfortunate that a bar has formed just outside the entrance of the harbour, with a depth of water of four fathoms at low water, spring tides, so that ironclads of the largest size would be denied admittance.

There are at present, no steamers sailing direct from Borneo to England, and nearly all the commerce from British North Borneo ports is carried by local steamers to that great emporium of the trade of the Malayan countries, Singapore,

[116]distant from Sandakan a thousand miles, and it is a curious fact, that though many of the exports are ultimately intended for the China market,

e.g., edible birds'-nests, the Chinese traders find it pays them better to send their produce to Singapore in the first instance, instead of direct to Hongkong. This is partly accounted for by the further fact that, though the Government has spent considerable sum in endeavouring to attract Chinamen from China, the large proportion of our Chinese traders and of the Chinese population generally has come to us

viâ Singapore, after as it were having undergone there an education in the knowledge of Malayan affairs.

As further illustrating the commercial and strategical advantages of the harbours of British North Borneo, it should be noted that the course recommended by the Admiralty instructions for vessels proceeding to China from the Straits, viâ the Palawan passage, brings them within ninety miles of the harbours of the West Coast.

As to postal matters, British North Borneo, though not in the Postal Union, has entered into arrangements for the exchange of direct closed mails with the English Post Office, London, with which latter also, as well as with Singapore and India, a system of Parcel Post and of Post Office Orders has been established.

The postal and inland revenue stamps, distinguished by the lion, which has been adopted as the Company's badge, are well executed and in considerable demand with stamp collectors, owing to their rarity.

The Government also issues its own copper coinage, one cent and half-cent pieces, manufactured in Birmingham and of the same intrinsic value as those of Hongkong and the Straits Settlements.

The revenue derived from its issue is an important item to the Colony's finances, and considerable quantities have been put into circulation, not only within the limits of the Company's territory, but also in Brunai and in the British Colony of Labuan, where it has been proclaimed a legal tender on the condition of the Company, in return for the profit which they reap by its issue in the island, contributing to the impoverished Colonial Treasury the yearly sum of $3,000.

[117]Trade, however, is still, to a great extent, carried on by a system of barter with the Natives. The primitive currency medium in vogue under the native regime has been described in the Chapters on Brunai.

The silver currency is the Mexican and Spanish Dollar and the Japanese Yen, supplemented by the small silver coinage of the Straits Settlements. The Company has not yet minted any silver coinage, as the profit thereon is small, but in the absence of a bank, the Treasury, for the convenience of traders and planters, carries on banking business to a certain extent, and issues bank notes of the values of $1, $5 and $25, cash reserves equal to one-third of the value of the notes in circulation being maintained.

[18]

Sir Alfred Dent is taking steps to form a Banking Company at Sandakan, the establishment of which would materially assist in the development of the resources of the territory.

British North Borneo is not in telegraphic communication with any part of the world, except of course through Singapore, nor are there any local telegraphs. The question, however, of supplementing the existing cable between the Straits Settlements and China by another touching at British territory in Borneo has more than once been mooted, and may yet become a fait accompli. The Spanish Government appear to have decided to unite Sulu by telegraphic communication with the rest of the world, viâ Manila, and this will bring Sandakan within 180 miles of the telegraphic station.

Chapter IX.

In the eyes of the European planter, British North Borneo is chiefly interesting as a field for the cultivation of tobacco, in rivalry to Sumatra, and my readers may judge of the importance of this question from a glance at the following figures, which shew the dividends declared of late years by three of the principal Tobacco Planting Companies in the latter island:—

| In | Dividends paid by |

| The Deli Maatschappi. | The Tabak Maatschappi. | The Amsterdam Deli Co. |

| 1882 | 65 | per cent. | 25 | per cent. | 10 | per cent. |

| 1883 | 101 | " | 50 | " | 30 | " |

| 1884 | 77 | " | 60 | " | 30 | " |

| 1885 | 107 | " | 100 | " | 60 | " |

| 1885 | 108 | " | ..... | ..... |

In Sumatra, under Dutch rule, tobacco culture can at present only be carried on in certain districts, where the soil is suitable and where the natives are not hostile, and, as most of the best land has been taken up, and planters are beginning to feel harassed by the stringent regulations and heavy taxation of the Dutch Government, both Dutch and German planters are turning their attention to British North Borneo, where they find the regulations easier, and the authorities most anxious to welcome them, while, owing to the scanty population, there is plenty of available land. It is but fair to say that the first experiment in North Borneo was made by an English, or rather an Anglo-Chinese Company, the China-Sabah Land Farming Company, who, on hurriedly selected land in Sandakan and under the disadvantages which usually attend pioneers in a new country, shipped a crop to England which was pronounced by experts in 1886 to equal in quality the best Sumatra-grown leaf. Unfortunately, this Company, which had wasted its resources on various experiments, instead of confining itself to tobacco planting, was unable to continue its operations, but a Dutch planter from Java, Count

Geloes d'Elsloo, having carefully selected his land in Marudu Bay, obtained, in 1887, the high average of $1 per lb. for his trial crop at Amsterdam, and, having formed an influential Company in Europe, is energetically bringing a large area under

[119]cultivation, and has informed me that he confidently expects to rival Sumatra, not only in quality, but also in quantity of leaf per acre, as some of his men have cut twelve pikuls per field, whereas six pikuls per field is usually considered a good crop. The question of "quantity" is a very important one, for quality without quantity will never pay on a tobacco estate. Several Dutchmen have followed Count

Geloes' example, and two German Companies and one British are now at work in the country. Altogether, fully 350,000 acres

[19] of land have been taken up for tobacco cultivation in British North Borneo up to the present time.

In selecting land for this crop, climate, that is, temperature and rainfall, has equally to be considered with richness of soil. For example, the soil of Java is as rich, or richer than that of Sumatra, but owing to its much smaller rainfall, the tobacco it produces commands nothing like the prices fetched by that of the former. The seasons and rainfall in Borneo are found to be very similar to those of Sumatra. The average recorded annual rainfall at Sandakan for the last seven years is given by Dr. Walker, the Principal Medical Officer, as 124.34 inches, the range being from 156.9 to 101.26 inches per annum.

Being so near the equator, roughly speaking between N. Latitudes 4 and 7, North Borneo has, unfortunately for the European residents whose lot is cast there, nothing that can be called a winter, the temperature remaining much about the same from year's end to year's end. It used to seem to me that during the day the thermometer was generally about 83 or 85 in the shade, but, I believe, taking the year all round, night and day, the mean temperature is 81, and the extremes recorded on the coast line are 67.5 and 94.5. Dr.

Walkerhas not yet extended his stations to the hills in the interior, but mentions it as probable that freezing point is occasionally reached near the top of the Kinabalu Mountains, which is 13,700 feet high; he adds that the lowest recorded temperature he has found is 36.5, given by Sir

Spencer St. John in his "Life in the Forests of the Far East." Snow has never

[120]been reported even on Kinabalu, and I am informed that the Charles Louis Mountains in Dutch New Guinea, are the only ones in tropical Asia where the limit of perpetual snow is attained. I must stop to say a word in praise of Kinabalu, "the Chinese Widow,"

[20] the sacred mountain of North Borneo whither the souls of the righteous Dusuns ascend after death. It can be seen from both coasts, and appears to rear its isolated, solid bulk almost straight out of the level country, so dwarfed are the neighbouring hills by its height of 13,680 feet. The best view of it is obtained, either at sunrise or at sunset, from the deck of a ship proceeding along the West Coast, from which it is about twenty miles inland. During the day time the Widow, as a rule, modestly veils her features in the clouds.

The effect when its huge mass is lighted up at evening by the last rays of the setting sun is truly magnificent.

On the spurs of Kinabalu and on the other lofty hills, of which there is an abundance, no doubt, as the country becomes opened up by roads many suitable sites for sanitoria will be discovered, and the day will come when these hill sides, like those of Ceylon and Java, will be covered with thriving plantations.

Failing winter, the Bornean has to be content with the the change afforded by a dry and a wet season, the latter being looked upon as the "winter," and prevailing during the month of November, December and January. But though the two seasons are sufficiently well defined and to be depended upon by planters, yet there is never a month during the dry season when no rain falls, nor in the wet season are fine days at all rare. The dryest months appear to be March and April, and in June there generally occurs what DoctorWalker terms an "intermediate" and moderately wet period.

Tobacco is a crop which yields quick returns, for in about 110 to 120 days after the seed is sown the plant is ripe for cutting. The

modus operandi is somewhat after this fashion. First select your land, virgin soil covered with untouched

[121] jungle, situated at a distance from the sea, so that no salt breezes may jeopardise the proper burning qualities of the future crop, and as devoid as possible of hills. Then, a point of primary importance which will be again referred to, engage your Chinese coolies, who have to sign agreements for fixed periods, and to be carefully watched afterwards, as it is the custom to give them cash advances on signing, the repayment of which they frequently endeavour to avoid by slipping away just before your vessel sails and probably engaging themselves to another master.

Without the Chinese cooly, the tobacco planter is helpless, and if the proper season is allowed to pass, a whole year may be lost. The Chinaman is too expensive a machine to be employed on felling the forest, and for this purpose, indeed, the Malay is more suitable and the work is accordingly given him to do under contract. Simultaneously with the felling, a track should be cut right through the heart of the estate by the natives, to be afterwards ditched and drained and made passable for carts by the Chinese coolies.

That as much as possible of the felled jungle should be burned up is so important a matter and one that so greatly affects the individual Chinese labourer, that it is not left to the Malays to do, but, on the completion of the felling, the whole area which is to be planted is divided out into "fields," of about one acre each, and each "field" is assigned by lot to a Chinese cooly, whose duty it is to carefully burn the timber and plant, tend and finally cut the tobacco on his own division, for which he is remunerated in accordance with the quality and quantity of the leaf he is able to bring into the drying sheds. Each "field," having been cleared as carefully as may be of the felled timber, is next thoroughly hoed up, and a small "nursery" prepared in which the seeds provided by the manager are planted and protected from rain and sun by palm leaf mats (

kajangs) raised on sticks. In about a week, the young plants appear, and the Chinese tenant, as I may call him, has to carefully water them morning and evening. As the young seedlings grow up, their enemy, the worms and grubs, find them out and attack them in such numbers that at least once a day, sometimes oftener, the anxious planter

[122]has to go through his nursery and pick them off, otherwise in a short time he would have no tobacco to plant out. About thirty days after the seed has been sown, the seedlings are old enough to be planted out in the field, which has been all the time carefully prepared for their reception. The first thing to be done is to make holes in the soil, at distances of two feet one way and three feet the other, the earth in them being loosened and broken up so that the tender roots should meet with no obstacles to their growth. As the holes are ready for them, the seedlings are taken from the nursery and planted out, being protected from the sun's rays either by fern, or coarse grass, or, in the best managed estates, by a piece of wood, like a roofing shingle, inserted in the soil in such a way as to provide the required shelter. The watering has to be continued till the plants have struck root, when the protecting shelter is removed and the earth banked up round them, care being taken to daily inspect them and remove the worms which have followed them from the nursery. The next operation is that of "topping" the plants, that is, of stopping their further growth by nipping off the heads.

According to the richness of the soil and the general appearance of the plants, this is ordered to be done by the European overseer after a certain number of leaves have been produced. If the soil is poor, perhaps only fourteen leaves will be allowed, while on the richest land the plant can stand and properly ripen as many as twenty-four leaves. The signs of ripening, which generally takes place in about three months from the date of transplantation, are well known to the overseers and are first shewn by a yellow tinge becoming apparent at the tips of the leaves.

The cooly thereupon cuts the plants down close to the ground and lightly and carefully packs them into long baskets so as not to injure the leaves, and carries them to the drying sheds. There they are examined by the overseer of his division, who credits him with the value, based on the quantity and quality of the crop he brings in, the price ranging from $1 up to $8 per thousand trees. The plants are then tied in rows on sticks, heads downwards, and hoisted up in tiers to dry in the shed.

[123]After hanging for a fortnight, they are sufficiently dry and, being lowered down, are stripped of their leaves, which are tied up into small bundles, similar leaves being roughly sorted together.

The bundles of leaves are then taken to other sheds, where the very important process of fermenting them is carried out. For this purpose, they are put into orderly arranged heaps—small at first, but increased in size till very little heat is given out, the heat being tested by a thermometer, or even an ordinary piece of stick inserted into them. When the fermentation is nearly completed and the leaves have attained a fixed colour, they are carefully sorted according to colour, spottiness and freedom from injury of any kind. The price realized in Europe is greatly affected by the care with which the leaves have been fermented and sorted. Spottiness is not always considered a defect, as it is caused by the sun shining on the leaves when they have drops of rain on them, and to this the best leaves are liable; but spotted leaves, broken leaves and in short leaves having the same characteristics should be carefully sorted together. After this sorting is completed as regards class and quality, there is a further sorting in regard to length, and the leaves are then tied together in bundles of thirty-five. These bundles are put into large heaps and, when no more heating is apparent, they are ready to be pressed under a strong screw press and sewn up in bags which are carefully marked and shipped off to Europe—to Amsterdam as a rule.

As the coolies' payment is by "results," it is their interest to take the greatest care of their crops; but for any outside work they may be called on to perform, and for their services as sorters, etc. in the sheds, they are paid extra. During the whole time, also, they receive, for "subsistence" money, $4 or $3 a month. At the end of the season their accounts are made up, being debited with the amount of the original advance, subsistence money and cost of implements, and credited with the value of the tobacco brought in and any wages that may be due for outside work. Each estate possesses a hospital, in which bad cases are treated by a qualified practitioner, while in trifling cases the European overseer dispenses drugs,

[124] quinine being that in most demand. If, owing to sickness, or other cause, the cooly has required assistance in his field, the cost thereof is deducted in his final account.

The men live in well constructed "barracks," erected by the owner of the estate, and it is one of the duties of the Chinese "tindals," or overseers acting under the Europeans to see that they are kept in a cleanly, sanitary condition.

The European overseers are under the orders of the head manager, and an estate is divided in such a way that each overseer shall have under his direct control and be responsible for the proper cultivation of about 100 fields. He receives a fixed salary, but his interest in his division is augmented by the fact that he will receive a commission on the value of the crop it produces. His work is onerous and, during the season, he has little time to himself, but should be here, there, and everywhere in his division, seeing that the coolies come out to work at the stated times, that no field is allowed to get in a backward state, and that worms are carefully removed, and, as a large proportion of the men are probablysinkehs, that is, new arrivals who have never been on a tobacco estate before, he has, with the assistance of the tindals, to instruct them in their work. When the crop is brought in, he has to examine each cooly's contribution, carefully inspecting each leaf, and keeping an account of the value and quantity of each.

Physical strength, intelligence and an innate desire of amassing dollars, are three essential qualifications for a good tobacco cooly, and, so far, they have only been found united in the Chinaman, the European being out of the question as a field-labourer in the tropics.

The coolies are, as a rule, procured through Chinese cooly brokers in Penang or Singapore, but as regards North Borneo, the charges for commission, transport and the advances—many of which, owing to death, sickness and desertion, are never repaid—have become so heavy as to be almost prohibitive, and my energetic friend, Count

Geloes, has set the example of procuring his coolies direct from China, instead of by the old fashioned, roundabout way of the extortionate labour-brokers of the Straits Settlements. North Borneo, it will be remembered, is situated midway between Hongkong and

[125]Singapore, and the Court of Directors of the Governing Company could do nothing better calculated to ensure the success of their public-spirited enterprise than to inaugurate regular, direct steam communication between their territory and Hongkong. In the first instance, this could only be effected by a Government subsidy or guarantee, but it is probable that, in a short time, a cargo and passenger traffic would grow up which would permit of the subsidy being gradually withdrawn.

Many of the best men on a well managed estate will re-engage themselves on the expiration of their term of agreement, receiving a fresh advance, and some of them can be trusted to go back to China and engage their clansmen for the estate.

In British North Borneo the general welfare of the indentured coolies is looked after by Government Officials, who act under the provisions of a law entitled "The Estate Coolies and Labourers Protection Proclamation, 1883."

Owing to the expense of procuring coolies and to the fact that every operation of tobacco planting must be performed punctually at the proper season of the year, and to the desirability of encouraging coolies to re-engage themselves, it is manifestly the planters' interest to treat his employés well, and to provide, so far as possible, for their health and comfort on the estate, but, notwithstanding all the care that may be taken, a considerable amount of sickness and many deaths must be allowed for on tobacco estates, which, as a rule, are opened on virgin soil; for, so long as there remains any untouched land on his estate, the planter rarely makes use of land off which a crop has been taken.

In North Borneo the jungle is generally felled towards the end of the wet season, and planting commences in April or May. The Native Dusun, Sulu and Brunai labour is available for jungle-felling and house-building, and nibong palms for posts and nipa palms for thatch, walls and kajangs exist in abundance.

Writing to the Court of Directors in 1884 I said:—"The experiment in the Suanlambah conclusively proves so far that this country will do for tobacco.

* * * There seems every reason to conclude that it will do as well here as in Sumatra. When this fact becomes known, I presume there will be

[126]quite a small rush to the country, as the Dutch Government, I hear, is not popular in Sumatra, and land available for tobacco there is becoming scarcer."

My anticipations have been verified, and the rush is already taking place.

The localities at present in favour with tobacco planters are Marudu Bay and Banguey Island in the North, Labuk Bay and Darvel Bay in the neighbourhood of the Silam Station, and the Kinabatangan River on the East.

The firstcomers obtained their land on very easy terms, some of them at 30 cents an acre, but the Court has now issued an order that in future no planting land is to be disposed of for a less sum than $1

[21] per acre, free of quit-rent and on a lease for 999 years, with clauses providing that a certain proportion be brought under cultivation.

At present no export duty is levied on tobacco shipped from North Borneo, and the Company has engaged that no such duty shall be imposed before the 1st January, 1892, after which date it will be optional with them to levy an export royalty at the rate of one dollar cent, or a halfpenny, per lb., which rate, they promise, shall not be exceeded during the succeeding twenty years.

The tobacco cultivated in Sumatra and British North Borneo is used chiefly for wrappers for cigars, for which purpose a very fine, thin, elastic leaf is required and one that has a good colour and will burn well and evenly, with a fine white ash. This quality of leaf commands a much higher price than ordinary kinds, and, as stated, Count Geloes'trial crop, from the Ranan Estate in Marudu Bay, averaged 1.83 guilders, or about $1 (3⁄2) per lb. It is said that 2 lbs. or 21⁄2 lbs. weight of Bornean tobacco will cover 1,000 cigars.

Tobacco is not a new culture in Borneo, as some of the hill natives on the West Coast of North Borneo have grown it in a rough and ready way for years past, supplying the population of Brunai and surrounding districts with a sun-dried article, which used to be preferred to that produced in Java. The Malay name for tobacco is

tambako, a corruption of the

[127]Spanish and Portuguese term, but the Brunai people also know it as

sigup.

It was probably introduced into Malay countries by the Portuguese, who conquered Malacca in 1511, and by the Spanish, who settled in the Philippines in 1565. Its use has become universal with men, women and children, of all tribes and of all ranks. The native mode of using tobacco has been referred to in my description of Brunai.

Fibre-yielding plants are also now attracting attention in North Borneo, especially the Manila hemp (

Musa textilis) a species of banana, and pine-apples, both of which grow freely. The British Borneo Trading and Planting Company have acquired the patent for Borneo of

Death's fibre-cleaning machines, and are experimenting with these products on a considerable scale and, apparently, with good prospects of success.

[22] For a long time past, beautiful cloths have been manufactured of pine-apple fibre in the Philippines, and as it is said that orders have been received from France for Borneo pine-apple fibre, we shall perhaps soon see it used in England under the name of French

silk.

In the Government Experimental Garden at Silam, in Darvel Bay, cocoa, cinnamon and Liberian coffee have been found to do remarkably well. Sappan-wood and kapok or cotton flock also grow freely.

Chapter X.

Many people have a very erroneous idea of the objects and intentions of the British North Borneo Company. Some, with a dim recollection of untold wealth having been extracted from the natives of India in the early days of the Honourable East India Company, conceive that the Company can have no other object than that of fleecing our natives in order to pay dividends; but the old saying, that it is a difficult matter to steal a Highlander's pantaloons, is applicable to North Borneo, for only a magician could extract anything much worth having in the shape of loot from the easy going natives

[128]of the country, who, in a far more practical sense than the Christians of Europe, are ready to say "sufficient for the day is the evil thereof," and who do not look forward and provide for the future, or heap up riches to leave to their posterity.