*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ***

Thanks are due Messrs. Harper and Brothers and the editors of “The Criterion” and of “Everybody’s Magazine” for permission to republish parts of the chapters on Sulu, Zamboanga, and Bongao, respectively. Copyright, 1907

By L. C. Page & Company (Incorporated)

Entered at Stationers’ Hall, London

All rights reserved

First Impression, June, 1907

Colonial Press

Colonial Press

Electrotyped and Printed by C. H. Simonds & Co. Boston, U. S.

Contents

I. Introductory Statements

II. Dumaguete

III. Misamis

IV. Iligan

V. Cagavan

VI. Cebu

VII. Zamboanga

VIII. Sulu

IX. Bongao

X. Tampakan and the Home Stretch

A Woman’s Journey Through the Philippines

Chapter I

Introductory Statements

Life on a cable-ship would be a lotus-eating dream were it not for the cable. But the cable, like the Commissariat cam-u-el in Mr. Kipling’s “Oonts,” is—

“—a devil an’ a ostrich an’ a orphan child in one.”

Whether we are picking it up, or paying it out; whether it is lying inert, coil upon coil, in the tanks like some great gorged anaconda, or gliding along the propelling machinery into some other tank, or off into the sea at our bow or stern; whether the dynamometer shows its tension to be great or small; whether we are grappling for it, or underrunning it; whether it is a shore end to be landed, or a deep-sea splice to be made, the cable is sure to develop most alarming symptoms, and some learned doctor must constantly sit in the testing-room, his finger on the cable’s pulse, taking its temperature from time to time as if it were a fractious child with a bad attack of measles, the eruption in this case being faults or breaks or leakages or kinks.

The difficulty discovered, it must be localized. A hush falls over the ship. Down to the testing room go the experts. Seconds, minutes, hours crawl by. At last some one leaves the consultation for a brief space, frowning heavily and apparently deep in thought. No one dares address him, or ask the questions all are longing to have answered, and when his lips move silently we know that he is muttering over galvanometer readings to himself. During this time everyone talks in whispers, and not always intelligently, of the electrostatic capacity of the cable, absolute resistances, and the coefficients of correction, while the youngest member of the expedition neglects her beloved poodle, sonorously yclept “Snobbles,” and no longer hangs him head downward over the ship’s rail.

At last the fault is discovered, cut out, and a splice made, the tests showing the cable as good as new, whereupon the women return to their chiffons, the child to her games, and the men, not on duty, to their cigars, until the cessation of noise from the cable machinery, or the engine-room bell signalling “full speed astern” warns us something else may be amiss.

In the testing room, that Holy of Holies on board a cable-ship, the fate of the Burnside hangs upon a tiny, quivering spark of light thrown upon the scale by the galvanometer’s mirror. If this light jumps from side to side, or trembles nervously, or perhaps disappears entirely from the scale, our experts know the cable needs attention, and perhaps the ship will have to stop for hours at a time until the fault is located. If the trouble is not in the tanks, the paying-out machinery must be metamorphosed into a picking-up apparatus, and the cable already laid will be coiled back into the hold until the fault appears, when it will be cut out and the two ends of cable spliced. After this splice grows quite cool, tests are taken, and if they prove satisfactory, we again resume our paying out, knowing that while the spot of light on the galvanometer remains quietly in one position, the cable being laid is electrically sound, and we can proceed without interruption.

As may be imagined everyone on the ship got to think in megohms, and scientific terms clung to our conversation just as the tar from the cable tanks clung to our wearing apparel, while few among us but had wild nightmares wherein the cable became a sentient thing, and made faces at us as it leapt overboard in a continuous suicidal frenzy.

The cable-ship Burnside, as some may remember, was one of the first prizes captured in the Spanish War. She had been a Spanish merchant ship, the Rita, trading between Spain and all Spanish ports in the West Indies, and when captured by the Yale, early in April, 1898, was on her way to Havana with a cargo of goods. There is little about her now, however, to suggest a Spanish coaster, save the old bell marked “Rita” in front of the captain’s cabin. The sight of this bell always brings to mind the wild patriotism of those early days of our war with Spain, when love of country was grown to an absorbing passion which made one eager to surrender all for the nation’s honour, and stifled dread of impending separation—a separation that might be forever—despite the rebel heart’s fierce protest. The Rita’s bell reminds one also of a country less fortunate than our own, and sometimes when looking at it, one can almost fancy the terror and excitement of those aboard the Spanish coaster when the Yale swept down upon her on that memorable April afternoon. But it is a far cry from that day to this, and the Burnside, manned by American sailors, flying Old Glory where once waved the red and yellow of Spain’s insignia, and laying American cable in American waters, is a very different ship from the Rita, fleeing before her pursuers in the West Indies.

When the Burnside left Manila on December 23, 1900, for the cable laying expedition in the far South Seas, there were eight army officers aboard, six of whom belonged to the Signal Corps, the seventh being a young doctor, and the eighth a major and quartermaster in charge of the transport. Besides these there were civilian cable experts, Signal Corps soldiers, Hospital Corps men, Signal Corps natives, and the ship’s officers, crew, and servants. The only passengers on the trip were women, two and a half of us, the fraction standing for a young person of nine summers, the quartermaster’s little daughter, whom we shall dub Half-a-Woman, letting eighteen represent the unit of grown-up value.

Half-a-Woman was the queen of the ship, and held her court quite royally from the Powers-that-Be, our commanding officer, down to the roughest old salt in the forecastle. Having a child aboard gave the only real touch of Christmas to our tropical pretence of it. Everything else was lacking—the snow, the tree, the holly and wreaths, the Christmas carol, the dear ones so far away—but the little child was with us, and wherever children are there also will the Christmas spirit come, even though the thermometer registers ninety in the shade, and at the close of that long summer-hot day we all felt more than “richer by one mocking Christmas past.”

Half-a-Woman was also obliging enough to have a birthday on the trip, which we celebrated by a dinner in her honour, a very fine dinner which opened with clear turtle soup and ended with her favourite ice and a birthday cake of gigantic proportions, decorated with ornate chocolate roses and tiny incandescent lamps in place of the conventional age-enumerating candles, cable-ship birthday cakes being eminently scientific and up-to-date. Other people may have had birthdays en route, for we were away from Manila many weeks, but none were acknowledged; modesty doubtless constraining those older than Half-a-Woman from making a too ostentatious display of tell-tale incandescent lights.

It was a very busy trip, everyone on the ship being occupied, with the exception of the women who spent most of their time under the cool blue awning of the quarter-deck, where many a letter was written, and many a book read aloud and discussed, though more often we accomplished little, preferring to lie back in our long steamer chairs and watch the wooded islands with cloud shadows on their shaggy breasts drift slowly by and fade into the purple distance.

Now we would pass close to some luxuriantly overgrown shore where tall cocoanut-palms marched in endless procession along the white beach; now past hills where groups of bamboos swung back and forth in the warm breeze, and feathery palms and plantains, the sunlight flickering through their leaves, showed myriad tints of green and gold and misty gray; these in turn giving place to some volcanic mountain, bare and desolate. Then for hours there would be no land at all, only the wonderful horizonless blue of water and sky, the sunlight on the waves so dazzlingly bright as to hurt the eyes.

But nearly always in this thickly islanded sea there was land, either on one side or the other, land bearing strange names redolent of tropic richness, over whose pronunciation we would lazily disagree. Perhaps it would be but a cliff-bound coast or a group of barren islands in the distance, bluer even than the skies above them; perhaps some lofty mountain on whose ridges the white clouds lay like drifted snow; or perhaps a tier of forest-grown hills, rising one above the other, those nearest the water clothed in countless shades of green, verging from deepest olive to the tender tint of newly awakened buds in the springtime, those farthest away blue or violet against the horizon.

Golden days these were when Time himself grew young again, and, resting on his scythe, dreamed the sunlit hours away. Until eventide the summer skies above us slept, as did the summer seas below us, when both awakened from their slumbers flushed and rosy. On some evenings the heavy white clouds piled high in the west seemed to catch fire, the red blaze spreading over the heavens, to be reflected later in the mirror-like water of the sea. Then the crimson light would gradually change to amethyst and gold, with the sun hanging like a ball of flame between heaven and earth, while every conceivable colour, or combination of colours, played riotously over all in the kaleidoscopic shifting of the clouds. At last the sun would touch the horizon, sinking lower and lower into the sea, while the heavens lost their glory, taking on pale tints of purple and violet. A moment more and the swift darkness of the tropics would blot out every vestige of colour, for there is no twilight in the Philippines, no half-tones between the dazzling tropic sunset and the dusky tropic night.

Then there were other evenings when the colours lying in distinct strata looked not unlike celestial pousse-cafés, or perhaps some delicately blended shades of pink and blue and mauve, suggested to a feminine mind creations of millinery art; or yet again, when a sky that had been gray and sober all day suddenly blazed out into crimson and gold at sunset, one was irresistibly reminded of a “Quakeress grown worldly.”

And then would come the night and the wonderful starlit heavens of the tropics—

“—unfathom’d, untrod,

Save by even’ and morn and the angels of God.”

Every star sent a trail of light to the still water, seeming to fasten the sky to the sea with long silver skewers; wonderful phosphorescence played about beneath us like wraiths of drowned men luring one to destruction; while in the musical lap of the water against the ship’s side one almost fancied the sound of Lorelei’s singing. And then there were starless nights with only a red moon to shine through cloudy skies; and nights no less beautiful when all the world seemed shrouded in black velvet, when the dusky sea parted silently to let the boat pass through, and then closed behind it with no laugh or ripple of water to speed it onward, breathlessly still nights of fathomless darkness. The ship’s master, burdened with visions of coral reefs on a chartless coast, failed to appreciate the æsthetic beauty of sailing unknown seas in limitless darkness, and either anchored on such nights, or paced back and forth upon his bridge, longing for electric lighted heavens that would not play him such scurvy tricks.

And there were gray days, too, which only served to make more golden the sun-kissed ones; days when no observations could be taken with the sextant, to the huge disgust of the officer in charge of such work; days when the distant mountains loomed spectre-like through the mist, their sharp outlines vignetted into the sky. Occasionally the fog would lift a bit, just enough to reveal the rain-drenched islands around us, and then suddenly wipe them out of existence again, leaving the ship alone on a gray and shoreless sea.

As for amusements, these were not lacking, what with reading, writing, bag-punching, and playing games with the small girl while under way; and when at anchor there was always shooting, hunting, and fishing for the men, and for us all swimming off the ship’s side. This last was often done in shark-ridden waters, to the great disapproval of the ship’s officers, some of whom would stand on the well-deck, revolver in hand, while more than once a swift bullet was sent shrilling over our heads at some great fin rising out of the sea beyond. On our trip to and from Bongao, one of the Tawi Tawi Islands, on a wrecking expedition to save the launch Maud, stranded there on a coral reef, all the Signal Corps officers were at liberty, too, which made life on the ship even more agreeable, the delightful experience being again repeated on our return trip to Manila from Pasacao, Luzon.

When one considers that the ship laid approximately five hundred knots of cable, and travelled over three thousand knots on the trip, which does not include the Bongao wrecking expedition, it will be seen how difficult the work was, in that in every instance, save from Zamboanga, Mindanao, to Sulu, on the island of Sulu, we had to make a preliminary trip, sounding and taking observations, before the cable could be laid, the Spanish charts being worse than unreliable. Then, too, a government transport dragged our cable with her anchor at one place, a fierce tropical storm wrecked it at another, while careless Moro trench diggers bruised it with stones at a third, which meant many extra days of work for the Signal Corps at each of these places, and for us idle ones a continuation of pleasant experiences, the whole trip taking in all three and a half months.

Three and a half months of ideal summer weather from the last of December to the middle of April, and real summer weather at that, not the sham midwinter summer of the tourist who has his photograph taken attired in flannels and standing under a palm-tree in California, Florida, or the Mediterranean, only to shiveringly resume his normal attire as soon as possible. The Philippine winter climate is quite different, what some one has defined as the climate of heaven, warmth without heat and coolness without cold, when men sport linen or khaki continuously, and women wear lawns and organdies throughout the season, with a light wrap added thereto at night—if it chances to be becoming.

In a few years it will be to these southern seas that the millionaire brings his yacht for a winter cruise; it will be in these forests that he hunts for wild boar and deer, or shoots woodcock, duck, snipe, pigeons, and pheasants; in these waters that he fishes for the iridescent silver beauties that here abound. It will be on these sunlit shores invalids seeking health will find it, and here that huge sanitariums should be built, for despite the tales of pessimistic travellers, no lovelier climate exists than can be found in Philippine coast towns from the middle of November until the last of March. After that it becomes unbearably hot, and then one is in danger of all kinds of fevers or digestive troubles, and should, if possible, go to Japan to get cooled off.

Of course, even during the Garden-of-Eden months, one must take the same care of himself that he would in any country, and most of the travellers who write against the Philippine climate have, according to their own statements, lived most unhealthfully as regarded diet, shelter, exposure, and the like. During the hot season itself one can get along very comfortably in the Philippines, if he makes it a rule to live just as he would at home, only at half speed, if I may so express it.

But aside from its possibilities for the leisure class, what a world of interest the Philippines has in store for us from a governmental and commercial standpoint! What a treasure-trove it will prove to the historian, geographer, antiquarian, naturalist, geologist and ethnologist. At every stopping-place my little note-book was filled with statistics as to trade in hemp, cane-sugar, cocao, rice, copra, tobacco, and the like. I even had a hint here and there as to the geology of the group, but ruthlessly blue-pencilled out such bits of useful information, and while it may not be at all utilitarian, rejoice that I have been privileged to see these islands in a state of nature, before the engineer has honeycombed the virgin forest with iron rails; before the great heart of the hills is torn open for the gold, or coal, or iron to be found there; before the primitive plough, buffalo, and half-dressed native give way to the latest type of steam or electric apparatus for farming; before the picturesque girls pounding rice in wooden mortars step aside for noisy mills; before the electric light frightens away the tropic stars, and dims the lantern hanging from the gable of every nipa shack; before banking houses do away with the cocoanut into which thrifty natives drop their money, coin by coin, [26]through a slit in the top; before the sunlit stillness of these coast towns is marred by the jar and grind of factory machinery; before the child country is grown too old and too worldly-wise.

Chapter II

DumagueteDUMAGUETE

All day long men and boys, innocent of even an excuse for clothes, hovered about the ship in bancas or dugouts, chattering volubly with each other in Visayan, or begging us in broken Spanish to throw down coins that they might exhibit their natatorial accomplishments, and, when we finally yielded, diving with yells of delight for the bits of silver, seeming quite as much pleased, however, with chocolates wrapped in tin-foil as they had been with the money, and uttering shrill cries that sounded profanely like “Dam’me—dam’me,” to attract our attention.

When a coin was thrown overboard every one dived for it with becoming unanimity, and the water being very clear, we could see their frog-like motions as they swam downward after the vanishing prize, and the good-natured scuffle under water for its possession. Laughing, sputtering, coughing, they would come to the surface, shaking the water out of their bright eyes like so many cocker spaniels, the sun gleaming on their brown skins, their white teeth shining, as they pointed out the complacent victor, who would hold the money up that we might see it, before they would again begin their clamour of “Dam’me—dam’me,” and go through a pantomime of how quickly each personally would dive and bring it up, did we throw our donation in his direction.

When the supply of coins and candies had been exhausted, some one bethought him of throwing chunks of ice overboard, and as none among the natives had ever seen ice before, their amazement may well be imagined. The first boy to pick up a piece of the glittering whiteness let it drop with a howl, and when he caught his breath again warned the others in shrill staccato tones that he had been burned, that it was hot, muy caliente, wringing his hands as if, indeed, they had been scorched. Presently, finding that the burn left no mark and had stopped hurting, he shamefacedly picked up the ice again, shifting it from one hand to the other with the utmost rapidity, and occasionally crossing himself in the interim.

Meanwhile more ice had been thrown overboard, and the rest of the natives, not at all deterred by their comrade’s warning, examined the strange substance for themselves. Very excited were their comments, those in the far bancas scrambling over the intervening boats to see with their own eyes the miracle of hard water so cold that it was hot. They smelled and tasted of it, like so many monkeys, chattering excitedly the while, and they rubbed it on each other’s bare backs amid screams of genuine fright, while many tumbled overboard to escape the horrible sensation of having it touch their flesh, the superstitious being reminded, no doubt, of all the tales the padres had ever told them of hell or purgatory.

DIVING FOR ARTICLES FROM THE SHIP

Some thrifty and unimaginative souls tied up their bits of ice in cloths or packed them in small boxes, to take back to the village, while others, engrossed in their examination of the strange substance, transferred it from one hand to the other until, miracle of miracles, it had entirely disappeared. Others, emulating the laughing people on the big boat, put their pieces of ice into their mouths, but not for long at a time, as the intense cold made their teeth ache; while still others piously crossed themselves and refused to have aught to do with so manifest an invention of the Evil One.

Meanwhile, despite the fact of its being Christmas, the Signal Corps officers, men, and natives were hard at work establishing an office in the town, digging a trench for the shore end of the cable, and setting up the cable hut, packed in sections for convenience in transportation. Thirty Dumaguete natives were employed at twenty-five cents a day to help dig the trench and put up the hut, and they seemed very willing in their work and thought the remuneration princely.

So heavy was the surf in the early morning that the officers and soldiers going ashore had to be carried from the rowboats to the beach on the backs of natives, but it fortunately calmed down enough before we women went over in the afternoon to allow of our entering Dumaguete in a more conventional manner.

Being a fiesta, the town was full of natives from the provinces, all smartly dressed and all beaming with good-natured curiosity at the advent of two and a half American women,—the only Americanas most of them had ever seen,—and quite an escort gathered around us as, accompanied by the officers of the post and those from the ship not otherwise engaged, we walked down the dusty streets toward the cockpits, where in honour of the day there was to be a contest of unusual interest. At every corner came new recruits to swell the ranks of our followers. “Merry Christmas,” cried everyone in Spanish or Visayan, and “Merry Christmas” we responded, though June skies bending down toward tropical palms and soft winds just rustling the tops of tall bamboos, so that they cast flickering fern-like shadows over thatched nipa roofs, but ill suggested Christmas to an American mind.

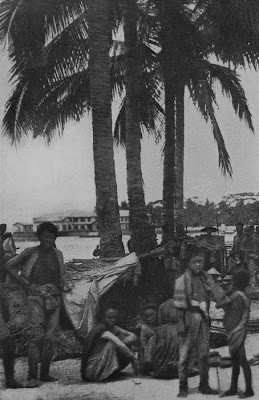

"HARD WORK ESTABLISHING AN OFFICE IN THE TOWN"

The audience, after watching this performance a moment or two, began making their bets, both individually and through the agency of the “farmer,” who, standing in the centre of the ring, cried out chaffingly in Visayan to faint-hearted gamesters. Then circles were drawn on the earthen floor of the pit, and the money put up on each cock deposited in one or the other of these rings. At the end of the fight some one appointed cried out the name of the victorious bird, and the winners swarmed down into the pit where they collected their money and the original stakes. There is never any cheating at such affairs, a sort of bolo morality existing among the natives, and all is as methodical and well-behaved as the proverbial Sabbath school.

It was the first cock-fight most of us cable-ship people had ever seen, and it was hard to understand the wild enthusiasm of the natives when, after unsheathing the steel gaffs on the roosters’ legs, the birds were allowed to make their preliminary dash at one another. For a moment they walked around the ring with an excessively polite air, each keeping a wary lookout on his antagonist, but frigidly impersonal and courteous. One might almost fancy them shaking hands before the combat should begin, so ceremonious was their attitude. Then there would come a simultaneous onslaught of feathered fury. Again and again they flew at one another, while the volatile audience called out excitedly in Spanish, “The black wins—No, the speckled one’s ahead. Holy Virgin, give strength to the black!” In a very few moments one cock is either dead, or perhaps turned coward before the cruel gaff of his opponent, and victor and vanquished leave the arena to new combatants, while the clink of coin changing hands is heard throughout the cockpit.

The first few fights we thought rather tame, and I, personally, had to assure myself over and over as the bloody contestants were removed from the scene of action, that such a death was no more painful and certainly far less ignominious than when chicken stewed or à la Maryland was to be the ultimate result of the fowl’s demise.

There was one little game-cock, however, who enthused even the most dispassionate among us. He was small and wiry, and his well kept white feathers testified to a devoted master. How impatient that absurd little rooster was for the fight to begin, and how he struggled to get off his gaff and go into the fray unarmed, the weight on his legs seeming an impediment to action, and how insolently he strutted and crowed before his antagonist, an equally well groomed gentleman of exceptional manners, attired in a gorgeous suit of green and gold. But handsome as the darker rooster was, the white one seemed to be the universal choice, and heavy were the stakes in his favour, so heavy that when, after a few minutes’ fighting, his wing was broken, a general groan went up throughout the cockpit, a groan which merged into sullen silence when the poor little chicken fell before the furious onslaught of his enemy.

Again and again the victorious green and gold rooster jumped upon his prostrate foe, pecking now at his crop, now at his eyes, in a perfect frenzy of triumphant rage, the little white fellow lying so still meanwhile that everyone thought him dead. But suddenly he struggled to his feet, and, despite the grievously broken wing, whipped the big bully in a way to raise a cheer even from the hitherto indifferent Americans.

As for the natives, they simply shouted themselves hoarse, and, contrary to all precedent, jumped down into the pit, throwing their sombreros on high and yelling vigorously, “Muy valiente gallo—muy valiente!” The little rascal had simply been sparring for wind, and he seemed to wink an eye at us after having chased his vanquished enemy to a corner, for, like the coward he was, the green and gold rooster turned tail and ran at the first opportunity.

It is to be hoped that the muy valiente gallo had his wing patched up and lived to tell his tale of bravery to many a barn-yard chick—a war-scarred veteran whose honourable wound entitled him to the respect of all domestic fowl. But knowing Filipino nature, I am rather inclined to think that the white rooster made a very acceptable broth for his master on the following day, the flesh of fighting-cocks being quite too tough for consumption in any other form.

On our return to the ship’s boat we were accompanied to the water’s edge by a juvenile contingent of natives, some of them being our friends of the forenoon, who returned any notice of themselves on our part by a rapturous gleam of teeth and eyes. One of them, a youngster of perhaps ten or eleven, who gloried in the euphonious name of Gogo, was particularly assidious in his attentions, and would come close up to us and say, “I-ese—i-ese—dam’me—i-ese!” going into paroxysms of mirth the while, and wrinkling up his handsome little face at the mere remembrance of the water so cold it was hard.

That night the shore officers took their Christmas dinner with us on the Burnside, and a very jolly evening we made of it. The saloon was entirely covered, ceiling and all, by American and ship’s flags, interspersed with palms, while over the sideboard were suspended the American flag and Union Jack intertwined, this last in honour of our two cable experts, both of them being Britishers. We women donned our smartest frocks, the electric piano, slightly out of tune, did rag-time to perfection, the menu included every conventional Christmas dish, and yet—and yet it was not Christmas, and all the roast turkey and plum pudding in the world could not make it so. It was a very jolly dinner, to be sure, well served and with charming company, but it was not a Christmas dinner. Only Half-a-Woman’s presence saved it and the day from utter failure.

The next morning the presidente of the town, other officials, and some of the leading men and women of Dumaguete made a visit to the ship, and were voluble in their surprise at what was shown them,—the electric lights and fans, the steam galley and ice-machine; the cold-storage room, where one could freeze to death in a few moments; the little buttons on the wall which one had only to touch and a servant appeared to take one’s orders; the wonderful piano that “played itself,”—all were duly admired and exclaimed over.

But what seemed to please and astonish them most of all were the bath-rooms with their white porcelain tubs, tiled floors, and shining silver knobs, which one had only to turn in order to have hot or cold water, either salt or fresh, in the tub, the basin, or the shower. Even the electric piano failed to impress them as did this aqueous marvel, and they crossed themselves and called on the Virgin and all her angels to testify that verily the American nation was a mighty one.

The men were of course greatly interested in our gallant armament of rapid-fire guns, and when the quartermaster, who is a crack shot, hit an improvised target in the water several times in succession with a one-pounder in the stern of the ship, the Filipinos were astounded, and stared at him in even greater admiration than they had shown for the formidable little weapon. Two shotguns of newest design were also brought on deck, and while the native women were frankly bored at this display of ordnance and preferred to talk about the way our gowns were made, the men were delighted, declaring they never imagined a gun could be broken in pieces and put together again so easily.

Before our guests left, lemonade and cake were served on the quarter-deck, and it was really amusing to watch their faces as they discussed the coldness of the drink, while the pieces of ice in their glasses excited as much perturbation as the untutored savages had shown the day before. One travelled lady, however, who had been to Iloilo once and tasted ice there, drank her lemonade with ostentatious indifference to its temperature, as became one versed in the ways of the world, explaining to me with condescension a few moments later that the Iloilo ice had been much colder than ours,—an item of physical research which I accepted politely.

We women were asked innumerable questions as to our respective ages, the extent of our incomes, our religious beliefs, and other inquiries of so personal a character as to be quite embarrassing. They seemed, though, to be very genuine in their admiration of us, and evinced great interest in our clothes, especially those of the quartermaster’s wife, who, being a recent arrival in the Philippines, had yet the enviable trail of the Parisian serpent upon her apparel. One heavy cloth walking-skirt of hers, fitting smoothly over the hips and with no visible means by which it could be got into, animated the same inquiry from these people as good King George is said to have made anent the mystery of getting the apple into the dumpling, a problem of no little difficulty, as any one will agree. At more than one stopping-place we were called upon to solve the riddle of that skirt, and I verily believe that, being women, they were even more awed at the thought of a garment fastening invisibly at one side of the front under a very deceptive little pocket than at all the electrical marvels shown them on the ship.

While in Dumaguete we were driven around the town and far out into the country surrounding it, finding everything much more tropical and luxuriant in growth than in Manila or its vicinity. There were giant cocoanut-palms, looking not unlike the royal palm so often spoken of by travellers on the Mediterranean, clusters of bamboo and groups of plantains, flowering shrubs and fields of young rice, green as a well kept lawn at home.

Picturesque natives saluted us from the roadway, or from the windows of their nipa shacks; naked brown children fled at our approach, and wakened their elders from afternoon siestas that they might see two white women and a yellow-haired child drive by; carabao, wallowing in the muddy water of a near-by stream, stared at us stolidly; fighting-cocks crowed lustily as we passed; and hens barely escaped with their cackling lives from under our very wheels.

"TWO WOMEN BEATING CLOTHES ON THE ROCKS OF A LITTLE STREAM

Everyone was friendly and peaceably disposed, everyone seemed glad to see us, if smiles and hearty greetings carry weight, and there was apparently no race prejudice, no half-concealed doubt or mistrust of us. Yet in a few days thereafter that very road became unsafe for an unarmed American, while the people who had greeted us with such childlike confidence and delight were preparing a warmer reception for the Americans under the able leadership of a Cebu villain, who had incited them to insurrection by playing upon their so-called religious belief, this in many instances being merely fetishism of the worst kind.

This instigator of anarchy boasted an anting-anting, a charm against bullets and a guarantee of ultimate success in battle, which consisted of a white camisa, the native shirt, on which was written in Latin a chapter from the Gospel of St. Luke. But notwithstanding his anting-anting, and the more potent factor of several hundred natives in his ranks, he was easily defeated by a mere handful of soldiers from the little fort, and when last heard of by our ship was lying in the American hospital at Dumaguete awaiting transportation to Guam. His former army was mucho amigo to the Americans, and once again the pretty drives around Dumaguete were quite safe, and once again the native, when passing an American, touched his hat and smilingly said good day in Visayan, a greeting which sounds uncommonly like “Give me a hairpin.”

On the evening of our second day in Dumaguete, the natives of the town gave a ball in honour of the cable-ship, at the house of one of the leading citizens. There, on a floor made smoother than glass with banana leaves, we danced far into the night to the frightfully quick music of the Filipino orchestra. One would hardly recognize the waltz or two-step as performed by the Visayan. He seems to take his exercise perpendicularly rather than horizontally, and after galloping through the air with my first native partner, I felt equal to hurdle jumping or a dash through paper hoops on the back of a milk-white circus charger.

Their rigadon, a square dance not unlike our lanciers, the Filipinos take very seriously, stepping through it with all the unsmiling dignity of our grandparents in the minuet. The sides not engaged in dancing always sit down between every figure and critically discuss those on the floor, but while going through the evolutions of the dance, it seems to be very bad form to either laugh or talk much, a point of etiquette I am afraid we Americans violated more than once. Another very graceful dance, the name of which I have forgotten, consists of four couples posturing to waltz time, changing from one partner to another as the dance progresses, and finally waltzing off with the original one, the motion of clinking castanets at different parts of the dance suggesting for it a Spanish origin.

At midnight a very attractive supper was served, to which the presidente escorted us with great formality. As is customary, the women all sat down first, the men talking together in another room and eagerly watching their chance to fill the vacant places as the women, one by one, straggled away from the table. The supper consisted for the most part of European edibles, but there were several Visayan delicacies as well, all of which I was brave enough to essay, to the great delight of the native women, who jabbered recipes for the different dishes into my ear, and pressed me to take a second helping of everything. All of them ate with their knives and wiped their mouths on the edge of the table-cloth, having Spanish precedent for such customs, and all were heartily and unaffectedly hungry after their violent exercise in the waltz and two step.

CHURCH AND CONVENTO, DUMAGUETE

It was very late when we finally left the baille, amidst much hand-shaking and many regrets that our stay in Dumaguete was so short, while great wonder was shown by all that we should be able to sail at daylight on the morrow, it seeming well-nigh incredible to the native mind that so much could have been accomplished in so short a time; for, despite the fact that we had been in Dumaguete less than two days, everything was completed—a marvel, indeed, when one considers the tremendous current which made the landing of the shore end a hazardous proceeding.

To one who has never witnessed the difficulties of propelling a rowboat through the heavy breakers of some of these Philippine coast towns, it would be hard to appreciate the struggles of the Signal Corps to land shore ends at the different cable stations. More than once men were almost drowned in its accomplishment but fortunately on the whole trip, despite many narrow escapes, not a man was seriously injured in the performance of his duty. Once landed on the beach, the shore end was laid in the trench dug for it, one end of the cable entering the cable hut through a small hole in its flooring, where after some adjustment and much shifting of plugs and coaxing of galvanometers, the ship way out in the bay was in communication with the land, through that tiny place, scarce larger than a sentry-box, in which a man has barely room enough to turn around.

Each telegraph office, when finally established, looks for all the world like a neat housekeeper’s storeroom, with its shelf after shelf of batteries, all neatly labelled like glass jars of jellies and jams. It positively made one’s mouth water to see them, and only the rows of wires on the wall, converging into the switchboard, and from thence to the operator’s desk, where the little telegraph instruments were so soon to click messages back and forth, could convince one that the jars contained only “juice,” as operators always call the electric current.

When this work on shore was completed, the ship paid out a mile and a half of cable, cut, and buoyed it, awaiting our return from the next station, where, because of the inaccurate charts already mentioned, it would be necessary to first take soundings before we could proceed to lay the cable. These buoys, so large that they were facetiously called “men” by the punster of the ship, are painted a brilliant scarlet, which makes them a conspicuous feature of the sea-scape. Sometimes a flagstaff and a flag are fastened to the buoy, and often it is converted for the ship’s benefit info an extemporaneous lighthouse by the addition of an oil lamp attached to its summit.

That night at Dumaguete the swift current unfortunately swung our ship’s anchor past the buoy to which the cable was attached, so that at daylight the next morning, instead of sailing for Oroquieta, Mindanao, as we bad expected, the buoy was picked up and a half mile of cable cut out, a new mile being spliced on in its place. When this was completed we paid out the fresh cable, buoyed it, and started for Oroquieta, which was to have been our next cable landing, stopping every five knots for soundings and observations.

One of the officers with the sextant ascertained the angle between two points on the coast, while other men, under the generalship of one of the cable experts, took deep-sea soundings, not only that the depth of the water might be known, but also its temperature and the character of the bottom, so one could judge of its effect upon the cable when laid, every idiosyncrasy of that cable being already a study of some import to the testing department.

This deep-sea sounding is a very necessary feature of cable laying, as unexpected depths of water or unlooked for changes in submarine geography, when not taken into account, might prove disastrous to the cable being laid. The sounding apparatus is of great interest, being a compact little affair consisting of a small engine that with a self-acting brake helps regulate the wire sounding-line as it is lowered into the water, and after sounding heaves it up again. When this weight touches bottom the drum ceases to revolve, due to the automatic brake, and the depth can be read off on the scale to one side of the apparatus. A cleverly devised little attachment to the sinker brings up in its grasp a specimen of sea bottom, so that one can ascertain if it be sand or rock, and whether or not it is suitable for cable laying.

The next day lingers in my memory as a profusely illustrated story, uneventful as to incident, and bound in the blue of sea and sky, with gilt edges of sunshine. Before our five o’clock breakfast we saw the “Cross hung low to the dawn,” and at night, anchored near our last sounding, fell asleep under the same Cross. The morning of the next day was but a repetition of the morning before, even to the early rising, for at our breakfast hour the moon had not yet turned out her light, nor were the stars a whit less brilliant than when we went to bed. “It’s too early for the morning to be well aired,” one of our cable experts was wont to whimsically complain at these daybreak gatherings, but by the time we had finished breakfast the night would have whitened into dawn, and before most people were astir an incredible amount of work had been accomplished by that little band of men, seemingly inured to fatigue and the loss of sleep.

All that morning on the way to Oroquieta the shore end of the cable was paid out of the tank and coiled in the hold ready for instant use when we should reach our destination. The music of the cable on the drum, the voice of some one in authority calling “Cobra—cobra,” to the natives in the tank, and their monotonous “Sigi do—sigi do,” half-sung, half-chanted, seemed an integral part of the day’s beauty. Even the natives themselves, guiding the heavy, unwieldy, treacherous cable round and round in the water-soaked tank, that only one turn should be lifted at a time, grinned affably and perspiringly at those of us peering over the railing at them—grimy tar-stained figures that they were, the sunlight bringing their faces out in strong relief against the dark backgound.

That afternoon we anchored off Oroquieta, but the surf was so heavy that it was felt unsafe to send one of the small boats ashore, especially as no one knew the location of the landing. Strangely enough, no boats of any kind came out to the ship, not even a native banca, so that our intercourse with Oroquieta was purely telescopic. Through our good lens we saw many a soldier, field-glass in hand, looking wistfully in our direction. Other soldiers walked up and down the beach on sentry duty, still others seemed to be standing guard over a small drove of horses in a palm grove a little to the right of the principal buildings, while many more lounged lazily on the broad steps of the church, or, leaning out of the windows of the tribunal, evidently used as a barracks, stared stolidly at the strange ship in the harbour. That every man wore side-arms seemed an indication the rebels were still rampant on the northern coast of Mindanao, and the fact of numberless native boats passing by with a pharisaical lack of interest in our presence spoke insurrection even more plainly.

Through the glass we all took turns in watching retreat, the little handful of khaki-clad men standing at attention as the stars and stripes fluttered down the flagstaff. Oroquieta was a lonely looking place, built entirely of nipa, with the exception of the inevitable white church and convento, so we were not sorry when the Powers-that-Be decided it was a poor cable landing, and gave orders for the ship to proceed to Misamis, Mindanao, on the following day. Early next morning we weighed anchor, and, still taking soundings, arrived off Misamis about ten o’clock, after a sail which one never could forget, as the coast of Mindanao is rarely beautiful and much more tropical than anything we had seen even on the island of Negros.

Chapter III

Misamis

Long before reaching Misamis the old gray fort at the entrance of the town was picked out by some one looking through the telescope, and many were the theories concerning it. At so great a distance, and with the hot sunlight shining full upon it, the fort might have been a strip of white sand; later it was decided to be a tribunal of unusual proportions, and at last when it loomed full upon us in all the picturesqueness of its gray, moss-grown walls, with weeds trailing in luxurious profusion from every crevice, we decided that there lived the American inhabitants of Misamis. Soldiers gathered under the roof of the nearest watch-tower to observe our entrance into the harbour, while still others, unmindful of the blazing sun, perched on the top of the wall and swung their feet over the side, doubtless making numerous wagers as to the transport’s name and its business in so out of the way a place as Misamis.

Owing to the unreliability of the Spanish charts, the Burnside anchored some distance out of the harbour, and just before tiffin a boat-load of officers from the garrison came out to the ship, accompanied by the titular captain of the port, a young chap who also acted in several other official capacities, a sort of military “crew, and the captain, too, and the mate of the Nancy Bell.” After tiffin the ship sailed into anchorage in the harbour of Misamis, half-way around the old fort, which seemed to grow more picturesque with every turn, till finally we could see the village of Misamis, almost hidden in a bewildering mass of tropical vegetation. Our numerous theories to the contrary, the old fort was uninhabited, save by the ghosts of other days, remaining but a grim relic of the time when Moro pirates swept terror to the hearts of all coast villages south of Luzon. It was within those historic walls that the Signal Corps decided to set up the cable-hut, and early the next morning two parties were sent ashore, one to establish an office in the town, the other to superintend [55]the digging of a trench by native prisoners, just outside the walls of the old fort.

Among these distinguished gentlemen was a so-called colonel of the insurrecto army who had been captured a short time before. The colonel posed as an aristocrat, whose hands had never been soiled by labour, and when his companions in confinement were turned out to assist in making way for liberty by means of the cable trench, he protested vigorously at the indignity, and averred that he was not seeking the opportunity of reimbursing the American government with pick and shovel for his enforced subsistence. He reiterated so often he was an officer and a gentleman, that finally the American major in command at Misamis mildly replied that self-appointed colonels in self-appointed armies were not recognized by any government, and as for his gentility, if it were the genuine article and not a veneer like his title, it would certainly stand the strain of a little honest labour. The arguments were cogent, and the hand of the law more irresistible still, so the high ranking officer took his turn in the trench with the other prisoners.

THE OLD FORT AT MISAMIS

The Misamis women were charmed with their white sisters, and could no more conceal their artless delight than so many children. They laughed and giggled nervously. They gesticulated as they talked, and shrugged their pretty shoulders with a grace taught them by our Spanish predecessors. They patted imaginary stray hairs into place in their sleek black coiffures, and settled camisa or panuela with indescribably quick and bird-like movements. Those of them who could speak Spanish talked clothes and babies and servants, or smiled politely at our mistakes in the language, laughing out-right at their own futile efforts to speak English. They were astonished that the quartermaster’s wife should have attained the remarkable height of five feet eight inches so young! Was it possible there were other women in America as tall? Taller even? ’Susmariajoseph! But surely that was a joke? One never could tell when these Americans were joking.

One of the officers presented the Burnside women with some native hats typical of the island, and the Filipinos were overcome with surprise at our interest in such ordinary headgear. What were we going to do with the hats? Wear them ourselves? Oh, no, we hastened to explain, they were to decorate our walls in America, that all our friends might see what pretty hats the Filipino people wear. Decorate the wall with hats? What a very curious idea! They chatted volubly over this idiosyncrasy, and even laughed at it, but quite decorously so that our feelings might be spared. Suddenly one of them, a most vivacious girl, and evidently the belle of the village, leaned over and in persuasive tones suggested that we women leave our hats, each real creations of millinery art, for their walls, at which witticism they all giggled explosively and shrugged their shoulders in rapturous appreciation of our confusion; all but the presidente’s wife, who looked shocked at such presumption and spoke to the younger women warningly in Visayan.

The only other shoes in the room, excepting those worn by the Americans and some few of the native men, were the proud possession of a tiny girl eight years old. This fashionable young person boasted also a European hat of coarse white straw stiffly trimmed with blue ribbon and blue ostrich tips. That the feathers had a wofully limp, depressed, and bedraggled appearance; that the ribbon was obviously cotton; and the straw of the coarsest weave, in no wise detracted from the glorious knowledge that it was a hat, a real hat such as the Americanas themselves were wearing. Sustained by this fact the young lady, who, in addition to the shoes and millinery, wore only a single other garment, comported herself with great dignity. Even in the trying circumstance of passing between one and the light, she was quite unconscious of anything amiss, the proud assurance of being dressed in the height of style as to her head and feet, precluding all worry as to minor details.

Among others met that afternoon at the Headquarters Building was a Spanish gentleman of charming manners. He invited our party from the ship, and the officers stationed in town, to stop at his house on our return to the launch and have some refreshments, an invitation we gladly accepted. So the courtly Castilian, beaming with hospitable intent, hurried ahead to prepare for our coming, we following shortly after in his footsteps. But to the young Spaniard’s ill concealed chagrin and our own embarrassment, the whole Filipino contingent accompanied us to the house. Fully as many more natives gathered at every available door and window, while outside the band, which had brought up a tuneful and triumphant rear, played the “Star Spangled Banner.” After all had partaken of Señor Montenegro’s enforced liberality, we repaired to the launch, accompanied by almost the entire population of Misamis, and amidst a shrill chorus of “Hasta la vista,” and “Adios,” we steamed back to the Burnside, whose twinkling lights shone out dimly against the evening sky.

The next morning a party of Signal Corps men, accompanied by a guard of fifteen soldiers from the fort, sailed at peep o’ day in the ship’s launches, the two in tandem towing a native banca loaded with cable, which was to be laid in the Lintogup River and upper Panguil Bay, a stretch of water too shallow for the Burnside herself to attempt its navigation. This cable was in turn to be connected at Lintogup with Tukuran, on the southern coast of Mindanao, by a land line across a mountainous country.

When the party started there were guns and ammunition enough on the two launches to have quelled a good sized insurrection, but as little was really known of the upper bay and river, and as many rumours were rife among the natives of Misamis as to warlike Moros and Monteses living on these shores, and more disquieting rumours still among the officers that it was a camping place for insurrectos, it was thought best to amply provide against any emergency.

THE LINTOGUP RIVER

Unfortunately, no information could be obtained as to the rise and fall of the tides or the strength of the current, a fact that delayed the expedition many days and necessitated the return of one or other of the launches for a renewal of rations, fresh water, and coal, not once but thrice. The first, second, and third relief expeditions, we called them, and teased the officer in charge unmercifully over his hard luck.

But at last, despite adverse winds and tides; despite the fact that one of the Filipino guides ran the launch aground, with malice aforethought, no doubt, as on his return to Misamis he was arrested on indubitable evidence as a spy; despite the fact that the sailing banca, ran on the bar, and while trying to pull her off she and her five miles of cable were swamped; despite the fact that the ship’s launch Grace, or the Disgrace, as she was afterward called, distinguished herself by blowing up twice and almost scalding everyone on board; despite the fact that all the odds were against the expedition’s success, and that it took six days and nights to accomplish what might have been done in a third of the time—despite all this, I say, the cable was at last laid and the luckless workers returned.

But, oh, the bitterness of life in general and that of a cable man in particular! For after all those heroic struggles the first test showed a fault, and, cruel fate, at the far end of Panguil Bay at that! The silence which greeted the reception of this terrible news was as profane as words, and the Powers-that-Be decided on the spot that enough work had been spent on that calamitous cable for the time being, and decided to proceed with the laying of the main lines, leaving the Lintogup stretch until a subsequent visit to Misamis.

Meanwhile there was much work accomplished in the town, a fine telegraph office being established on the principal street; and a trench completed by the shore end party; while much overhauling of the cable in the tanks, and daily drills given to the Signal Corps soldiers in cable telegraphy and the care of the instruments kept those aboard ship busy. Tic—tack, clic—clack, went the little telegraph instrument at one end of the quarter-deck, and clic—clack, tic—tack answered an instrument at the other end, hour after hour through the long, warm mornings, and the longer, warmer afternoons.

On New Year’s eve, several officers from the fort saw the century in with those of us remaining on the Burnside, but the time passed so pleasantly that no one remembered the auspicious occasion until the sound of sharp firing from the shore broke in upon our conversation. The jangling of church bells followed, and one of the shore officers, usually a very cool and self-contained young fellow, sprang to his feet, exclaiming as he buckled on his revolver, “Great heavens! An attack on the town and I not there. May I have a ship’s boat at once?” But even as he spoke the Burnside’s whistle blew a great blast, and several shots from the ship answered those on shore, every man with a revolver, shotgun, or rifle adding his quota of noise to the general hubbub.

And so it was the new century came to Mindanao, some thirteen hours ahead of its advent in New York or Washington. Before eight bells had ceased striking a search-light greeting was sent to our friends at Lintogup, but they, being tired after a hard day’s work, slept supinely on, unaware of our good wishes or the fact that a fine young century had been born to the old, old world.

I am sorry to relate that the next day a court-martial was held in Misamis to try the irrepressible guard who, in a burst of enthusiasm due to their first taste of twentieth century air, had fired off their rifles. The soldiers were sentenced rather heavily, rifle-shots in a Philippine town at that time being productive of dire results. Indeed, the shrill warning of the church bells and scattered shots in a Mindanao village meant one thing only, an uprising in the town or an attack from the outside, the incoming of a new century being of far less importance than the preservation of order and quiet in the garrison, and no cognizance could be taken of a new year which must be ushered in with a clang of firearms or the jangle of church bells—shrill heralds of disaster.

On New Year’s morning the presidente and secretario of Misamis, accompanied by their respective families and a young Moro slave, the property of the secretario, came aboard the Burnside to return our call. It was the first time any of them had ever seen a modern steamship, and loud and voluble were their exclamations of wonder at what we have come to regard as the every-day conveniences of civilization. After seeing the electric light, electric fans, and the shower baths turned on and off several times, the presidente craved permission to essay these miracles himself, and, to his own great surprise, accomplished supernatural results. The old wife watched him tremblingly. Surely, these were works of the Evil One, and, as such, to be left to heretics. But still the man persisted in his madness, and with a turn of his wrist brought light out of darkness or water and wind from the very walls.

Finally he turned around, and with a humourous twinkle in his eye, that belied the gravity of the rest of his face, he said: “The Americanos are a great people—a wonderful people—and how unlike the Filipinos! When a Filipino wants sunshine or rain or wind, he must wait until the good Lord gives it to him. When an Americano wants sunshine or rain or wind, he turns it on!”

The whole party was intensely interested in the big telescope which drew Misamis within a stone’s throw of the ship, and they could not in the least understand how we cooked in the steam galley without any fuel, while the ice-machine and cold storage rooms were quite beyond their comprehension, none of them ever having seen ice before. Of course, on seeing the strange substance, it must be tasted as well, so iced drinks were served on the quarter-deck, these being received with much preliminary trepidation and ultimate gustatory gratification. As for the small Moro slave, I only hope he did not die from his excessive libations, for he drank unnumbered glasses of lemonade, making most violent faces the while, and rubbing his small round stomach continually, as if the unaccustomed cold had penetrated to his very vitals.

On going ashore, each of the three children carried back a box of American candy, the order of our guests’ departure being somewhat delayed by Señora Presidente’s intense fear of going down the gangway. As I have said before, she was a fat old lady, and the way was steep; but finally, after much persuasion, she slipped her bare feet out of their velvet chinelas, gathered her voluminous skirts close about her, and, seating herself upon the top step of the ladder, slid down! Surely a simple solution of the difficulty.

That evening a ball was given in our honour at the Headquarters Building, which for the time being was transformed into a most attractive place with palms and flags and coloured lanterns, while just outside the broad windows a wonderful tropic sky, hung with silver stars, added its enchantment to the scene. No carriage being available in the town, we walked from the dingy little wharf to the Headquarters Building, arrayed in our very best, and followed by a guard of armed soldiers, our escorts themselves wearing revolvers.

At every corner a dark form would shoot out suddenly from the shadows and there would be the swift click of a rifle as it came to position, while a voice cried, “Halt! Who’s there?” “A friend,” some one would reply, or “Officer of the garrison,” as the case might be. Then again would come the sentinel’s voice telling the person challenged to advance and be recognized, at which one of the number would march forward, and, on being identified, the rest of us were allowed to pass the sentinel, who, meanwhile, kept his rifle at a port, his keen eye watching closely, that no enemy slip by under our protection.

It was a rarely beautiful night even for the tropics, that first of January, and as we women wore no wraps of any description, the contrast between our satins and chiffons and the rough khaki clothes of the soldiers was a strange one; and still stranger was the fact of our going under guard to a ball, a ball that at any moment might be interrupted by the bugles blowing a call to arms, whereupon our partners would have to desert us, perhaps to quell an uprising in the town, perhaps to defend it against an attack from the outside.

But fortunately the occasion was not marred by any such sinister happening, and doubtless still lives in the annals of Misamis as a very grand affair, for everyone of consequence in town was invited to the baille, and everyone invited came, not to mention those not invited who came also. When we arrived the rooms were quite crowded and the dancing had begun. Far down the street we heard the music and the sound of the women’s heelless slippers shuffling over the polished floor to a breathlessly fast waltz. If possible the people of Misamis dance faster and hop higher than the people of Dumaguete, and how the women manage to keep on their chinelas during these wild gyrations is quite beyond me.

As the secretario of the town played a harp in the orchestra—surely an evidence of versatility—we ventured to ask if he would play a two-step very, very slowly, and hummed it in ordinary time. At its beginning the Filipinos who had started to dance, stopped aghast. “Faster, faster!” they cried in Spanish. “No one could dance to such slow music. This is a ball, men, not a funeral!” But the secretario held the orchestra back, and in a few moments the Americans had the floor to themselves, the Filipinos stopping partly because they found it impossible to dance to such slow music and partly because they wanted to watch us.

They were all astonished at the apparent lack of motion in American dancing and the fact that we got over the ground without hopping. Many of them asked officers stationed in the town if the women wore a special kind of shoe to balls, as they appeared to be standing still and yet moving at the same time, while one old man was heard explaining to his cronies that we wore little wheels attached to the soles of our slippers—he had seen them—so that we did not have to move at all, the men doing all the dancing and merely pushing us back and forth on the floor. So much for the glide step as contrasted with the hop, though it must be confessed that the natives were quite frank in liking their own dancing better than ours, one of the reasons being that it gave them so much more exercise.

During the evening the natives gave a Visayan dance, called in the native tongue “A Courtship.” As the name implies, a young man and woman dance it vis-à-vis, the man courting the woman rhythmically and to music, she at first resisting, flashing her dark eyes scornfully as she trips by him, holding her fan to her face until he looks the other way, then peeping over its top at him, only to turn her back in disdain when, emboldened by her interest, he approaches. Finally his attentions become more pronounced, at which the girl grows coy, dropping her eyes shyly as they dance past one another, and covering her face again and again from his too ardent gaze; now bending her supple waist from side to side in time with the passionate music; now closing her eyes languorously; now opening them wide and smiling at him tenderly over the top of her fan, a graceful accomplice to her pretty coquetry. At last she surrenders to the wooing, the happy pair dancing away together while the music plays faster and faster until at last it stops with a great crash, that, we trust, not being symbolical of infelicity in wedlock. The dance was very well done, and the native audience enjoyed it thoroughly, calling out chaffingly in Visayan to the couple on the floor, and occasionally beating time to the music with hand or foot.

It was at this ball we met for the first time a family of American mestizas—three sisters there were, if I remember rightly,—all pretty girls, with regular features and soft brown hair, this hair distinguishing them at once from the other women of the place with their more conventional blue-black tresses. It seems that the grandfather of these girls had been an American sailor, who for some reason or other was marooned at Cagayan, Mindanao. Making the most, or as a pessimist might think, the worst of a disadvantageous situation, he married a native girl and raised a large and presumably interesting family, his descendants being scattered all over the island. The Misamis branch were extremely aristocratic, and so proud of their blue blood that since the arrival of the American troops they have associated with no one else in the village. It is said that the girls even refer to the United States as “home,” and occasionally wear European clothes in preference to the far more becoming and picturesque costume of saya, camisa, and panuela.

While in Misamis I verily believe that family was pointed out to us twenty times at least, and whenever a man lowered his voice and started in with, “You see those girls over there? Well, their grandfather was an American—” I steeled myself for what was to follow, and expressed surprise and interest as politely as possible, for it is hard to attain conventional incredulity over a twice-told tale. After the genealogy of the family had been gone over, root and branch, we would invariably be told the story of how the grandfather, grown rich and prosperous in his island home, once went to Manila on a business trip. He had then lived in Mindanao over thirty years, during which time he had spoken nothing but Visayan, varied occasionally with bad Spanish.

His negotiations at the capital taking him to an English firm, he started to address them in his long unused mother tongue, when to his extreme mortification he found he could not speak a word of English. Again and again he tried, the harsh gutturals choking in his throat, until at last, flushed and angry, he was forced to transact his business in Spanish, all of which amused the Britishers to the chaffing point. Leaving the office, the American flung himself into the street, muttering savagely under his breath, a torrent of old memories surging through his brain, those harsh English words in his throat clamouring for utterance. On and on he went, until at a far corner he suddenly pulled himself up sharply, turned on his heel, [74]and with all speed walked back to the English firm, a shrewd smile playing about his hard old mouth. Throwing open the door of the office, he walked abruptly in, saying as he did so, in an unmistakable Yankee drawl, “Blankety blank blank it! I knew I could speak English. All I needed was a few good cuss words to start me off!”

On the afternoon of January 3d, a party of Monteses visited the Burnside. Gaily turbaned and skirted were these Moro men, their jackets fitting so tightly that some one suggested they must have grown on them, that they were “quite natural and spontaneous, like the leaves of trees or the plumage of birds.” One’s olfactory nerves also bore evidence that frequent ablutions or change of garments were not customary among our guests, and the fact that when shown over the ship they evinced but little interest in the bath spoke volumes.

Strange to say, what the Moros most admired were the brass railings around the walls of the saloon, and the brass rods down the different stairways, in fact all the brass fittings on the ship, a thing that puzzled us not a little until the interpreter explained that the Moros thought the brass was solid gold, and were naturally much impressed thereat. Firearms they also enthused over, and looked with envious eyes at the shotguns, rifles, and revolvers exhibited, evincing great delight at the six and the one pounder guns on the quarter-deck. With the greatest equanimity they accepted several little presents made them, nor deigned thanks of any sort for benefits received, stuffing the different articles into their wide girdles with a stolid indifference which was enlivened by a smile once only. This was at a case of needles given to the leading Datto or chief, which, through the interpreter, we told him were for the wives of his bosom; whereupon they all smiled broadly, the interpreter explaining it was because we had sent the needles to women, as among Mindanao Moros men do all the sewing.

Being Mohammedans, they were very careful not to eat anything while on board ship for fear of unconsciously transgressing the Holy Law, even refusing chocolate candy because it might contain pork. They were shown ice, but took little interest in it, nor did they seem surprised at the cold storage rooms or the electric lighting. It is possible they thought Americans had attained the one really great thing in having white skins, after which all else followed as a matter of course.

The next day we went to call on the presidente and his wife. They lived in a bare, forlorn old house, with nothing attractive about it save the floor of the sala, which was of beautiful hard wood polished with banana leaves until it would have served for a mirror. Everything was scrupulously clean, but bespoke poverty, from the inadequate furniture of the sala to the patches and darns on the old wife’s stiffly starched skirt of abaca. This poverty was all the result of the war, we were told, as much of their out of town property had been confiscated or ruthlessly destroyed by the insurgents because of the presidente’s unswerving loyalty to the American government.

Both the presidente and his señora were delighted to see us, and while he discoursed on politics and what the coming of the cable meant to the people of Mindanao, the good housewife bustled about and brought forth the greatest delicacies her larder afforded, laying them out with proud humility on the marble topped table of the sala. There were peaches and pears, canned in Japan, and served right from the tin; there were little pink frosted cakes made in times prehistoric, to judge from their mustiness, and carefully packed away in glass jars for just such great occasions; there was good guava jelly and a Muscatelle that breathed of sunny vineyards in Spain—indubitable evidence of better days.

The house was so bare and shabby that this gastronomic outlay seemed an unwarrantable expense, yet what could one do but accept their hospitality in the same generous spirit in which it was offered? So at ten o’clock of a steaming hot morning we cheerfully stuffed ourselves on badly preserved fruits, elderly small cakes with enamelled complexions, and tiny sips of liquid fragrance, our reward of merit being the little señora’s beaming face.

Indeed, she even stopped apologizing after a bit, and while the presidente was toasting everybody from the “Chief Magistrate of America” down to our very humble selves, she sent a muchacho out to borrow the hand-organ belonging to a neighbour, this musical instrument being highly venerated in Misamis. On its arrival the presidente himself turned the crank, and with such vigour that I feared a stroke of apoplexy on his part.

A little later, as we were leaving, the señora took us into what would have been the stable had they possessed horses, a large open space under the house, to the right of which a room had been partitioned off with bamboo. Inside this partition a Filipina servant worked the señora’s loom. Back and forth went the shuttle under the little maid’s deft fingers, and up and down went her slender bare foot on the treadle, so that even as we watched the striped red and cream abaca grew under our very eyes.

Unfortunately I became enthusiastic, and nothing would do but that the old lady must present me with several yards of the pretty stuff. I felt as if I should be tried for larceny, what with those indigestible fruits, the pink cheeked cakes, the Muscatelle, and finally the abaca. I protested vigorously, I even pleaded, but in vain.

“You are my daughter,” laughed the señora, happily, “my white daughter. The abaca is yours—coarse stuff that it is,” and she reached up timidly and kissed me, first on one cheek and then on the other, the joy of giving in her dear old eyes.

The next day dawned so clear and beautiful that three of us decided, there being little work on hand until the Lintogup party’s return, to take a long drive around Misamis, and if we had time to even go so far as its four outposts. On the previous day the presidente had unearthed a queer little carriage out of a junk heap, and put this conveyance and a wise looking piebald pony at our disposal. The carriage was an odd affair between a calesa and carromata in shape, or like a high surrey with a small seat for the driver in front. It was beautifully clean, with a new bit of carpet at our feet, and cushioned in sky-blue tapestry. As there was but a single seat at the back, in addition to the driver’s seat in front, one of the two men of our party offered to relieve the Filipino in charge of the trap, and do the driving himself, but the native shook his head, declaring we would find the pony unmanageable. We thought not, but the driver was firm, and although the back seat was not very wide, we piled in upon the sky-blue cushions, trying to look as pleasant as possible in the circumstances.

After some persuasion on the part of the Filipino, the piebald pony started and proved to be a fine little animal with an unusually clean and even gait. The air was fresh and invigorating, and as we passed other Burnside friends trudging through the sand of the beach or toiling laboriously along the dusty road of the town, we congratulated ourselves on securing the only available trap in the place, and marvelled at the way our pony covered ground.

“Why, any one could drive him,” remarked one of the trio. “He’s a fine little beast.” “To be sure,” assented the others. But just then a treacherous feminine hat blew off, and we had to stop and pick it up. That was but the work of an instant—the stopping—but when it came to starting again—well, you just ought to have seen how that piebald acted! He simply laughed at the idea, his laugh extending in ecstatic chuckles all the way down his spinal column till the very carriage shook with his mirth. Then he planted his two fore feet down hard as much as to say, “I challenge you to budge me one inch from this spot,” and though the Filipino threatened, entreated, implored, and finally beat him unmercifully with the handle of the whip, the piebald stood his ground.

At last the two men clambered out of the high vehicle, and after tugging for some minutes at the rope bridle, succeeded in starting the stubborn animal along, but at so furious a gait that they had all they could do to get up over the wheels and into their seat again. All went well for about a quarter of a mile, when to our surprise the driver started to turn around. “Here, hombre,” called one of the men, in what he was pleased to consider Spanish, “we don’t want to go home yet. We want to go to the outposts—way out, sabe?” Yes, he “sabed,” grinning broadly the while, but this, señor, was the outpost.

We were dumbfounded, and stared stupidly at the white tent among the trees. “Why don’t they call ’em inposts?” growled one of the men, and then to the driver, “Very well, hombre, take us to the other three. We want to see ’em all.” But this was easier said than done. Again our wise-looking piebald balked, and balked most awfully. Again the two men, at imminent danger to life and limb, jerked at the rope bridle, and again barely escaped with their lives as they performed the perilous acrobatic feat of falling headlong into the carriage while it was going at full speed.

After the sixth performance of this kind, one being at a street crossing where some raw cocoa beans were drying on a petate in the sun, and the three others at the different outposts, we decided among ourselves that we had best dismiss our cochero and return to the ship, since it had taken us more than two hours to drive where we might have walked in thirty minutes.

It was here a most embarrassing situation arose, for just as we were debating what to pay our Jehu, something in my boot heels suggested that perhaps the native was not a coachman at all, but a Filipino gentleman taking us to drive at the request of the presidente. There was the sign manual of Misamis’s four hundred about him. He wore shoes. Moreover, he sported a very large and very yellow twenty dollar gold piece on his watch-chain. But stronger even than these evidences of native gentility was the freedom from restraint in the very frequent remarks he had tentatively thrown over his shoulder during the drive, and the fact that he had not weakened when, on first coming ashore, we had tried to browbeat him out of driving the horse.

“But if he is a cochero, and we don’t pay him, he’ll think we’re cheating him,” wailed one of us.

“And if he isn’t a cochero, and we do pay him, he’ll be indignant,” affirmed another.

My boot heels gave me another suggestion. Being a woman, I suppose I have intuitions, but I trust my boot heels every time. They are more reliable. “How would it do,” I suggested, with a consciousness of superiority which I trust did not sound in my voice, “How would it do to stop a sentinel and ask whether our friend is a coachman or the mayor of the town?” and even as I spoke a sentinel hove in sight and was promptly interrogated by the men.

“Him?” returned the soldier in answer to our questions, “Him? Why, he’s the richest man in these parts, I reckon, and holds some big job under the government. I forget what just now, but provost marshal, chief of police, or somethin’ like that.” We gasped at our narrow escape, and after getting that villainous automobile horse in motion again, pressed some cigars upon our distinguished host, and on reaching the dock thanked him heartily for our charming morning, impressing upon him that the Burnside was at his disposition at any and all times, an invitation of which he later availed himself.