The tragic Encounter between Special Action Force (SAF) of the Philippine National Police and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) on 25th Jan. 2015.

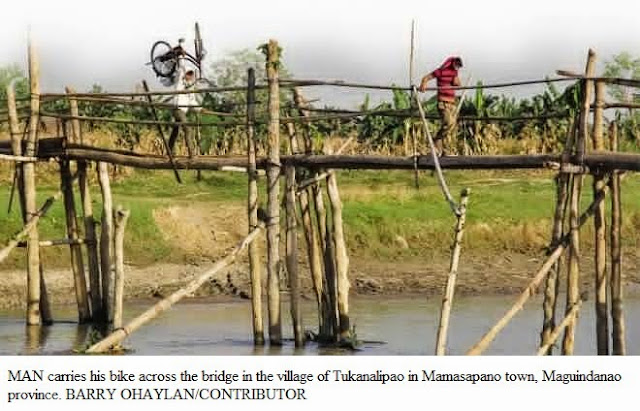

Below is the aerial view of Barangay Tukanalipao of Mamasapano,

Maguindanao, the scene of the tragic clash.

Maguindanao, the scene of the tragic clash.

Mamasapano : Time on Target

By : Patricia Evangelista Published 11:18 AM, Mar 20, 2015

It is difficult to accept that some failure to coordinate can lead to the blood of 44 policemen splashed across a cornfield south of the country.

They came in the dark, dropping out of vans and trucks at the far end of the Tukanalipao highway. They marched through the wet fields, cutting through scarecrow stalks, humping grenade launchers and assault rifles and belts of ammunition slung across the ceramic plates of tactical vests, 300 bullets to a man.

There was a quarter moon overhead. The enemy was asleep. Their commander had told them that there could be enemies everywhere, but they would own the night.

They were the 84th Seaborne, the elite of the elite, the bulletproof boys of the Special Action Force trained by Uncle Sam. They had fought in urban hellholes, had seen mortars fall out of the sky, had survived prison breaks and alleged coups, and long weeks of lying behind sandbags watching the horizon.

They had days of practice in Zamboanga, but Zamboanga wasn’t Maguindanao. The small town of Mamasapano was rebel country, and the fighters of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) were not the only men who slept that night. The MILF’s breakaway group, the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF), roamed the far end of the marshes. There were private armies, and M16s in the houses of farmers who had learned the hard way that justice comes from the barrel of the gun.

The enemy, when roused, could number in the thousands, and there were only 38 Seaborne crossing rivers whose GPS had just failed.

It took 6 hours, carrying equipment through muddy rivers and long stretches of flatland. They asked their guides to take over when navigation failed, but the guides got lost in the dark. They were late, an hour, two hours, and then they had to leave men behind at the last river.

When they finally arrived at their target in the village of Pidsandawan, they were 25 men and several radios short. Dawn was coming. They were running out of time.

They could have walked away, then and there, the same as they did in other missions. But Operation Exodus had no abort criteria.

At 4 in the morning of January 25, 2015, 13 men from the 84th Seaborne moved in to neutralize a bomb maker named Zulkifli Bin Hir, alias Marwan. It was impossible to hit 3 targets at once, so the two other targets, Abdul Basit Usman, and Amin Baco, alias Jihad, were left alone in favor of Marwan.

At 4:20 am Marwan was dead. They cut off his finger. They took their pictures. And then the firing started. Mortars fell, snipers took position, the gunfire raged like thunder as the men of the BIFF jumped into the fray. The 84th, lightly equipped, trained for operations with support bases ready to assist, were overwhelmed. They fired back.

When the sun rose, the enemy owned the day

“Why is it,” demands Senator Alan Peter Cayetano, "that when the PNP or AFP fail to coordinate, they are punished with the death penalty?”

Coordination is an innocuous word. Its associations are inoffensive, the crack of its consonants do not pulse with necessity. It is a process, an exchange, an attempt at integration. It is not a word that leaps from privilege speeches into primetime newscasts, unlike “terrorist” or “hero.”

Certainly it is difficult to accept that some failure to coordinate can lead to the blood of 44 policemen splashed across a cornfield in the country's south. There must be some other reason behind the deaths of 67 people, some evil afoot, some grave and fundamental trouble beyond basic incompetence that can explain the horror of one Sunday in January. People are dead. Children are orphaned. Wives are now widows. It is easier to speak of traitors and patriots and the betrayal of Moro brothers. We must die for the sake of peace. We must be willing to kill in the name of justice. We are one nation, under God. If we broke the ceasefire, if we failed to coordinate, it is not our fault. We do not negotiate with terrorists.

Cayetano points a finger at MILF chief negotiator Mohagher Iqbal.

“Why is it that when it comes to our military and police, when they enter your area, your answer is always, ‘No coordination?’”

Cry havoc, brothers. Let slip the dogs of war.The new strategy

The plan was called Exodus. The targets were high-value terrorists. The contents of the intelligence packet – built with the assistance of the United States – included a location in a remote area of Mamasapano.

Mamasapano offered a series of complications. Protocols under a ceasefire agreement signed between the MILF and the government required prior coordination before armed operations in MILF bailiwicks.

In their assessment, the SAF marked the MILF as enemy troops. The operation was planned for 2 am, while locals were asleep. The SAF were to have the advantage of night vision goggles.

A map was drawn up, dividing the route into waypoints. The 84th Seaborne would compose the main effort, 38 commandos whose duty was to neutralize the 3 targets. The 55th SAC would be their blocking force stationed behind them. Three other teams – the 41st, the 42nd, and the 45th – would be dispersed at waypoints along the route, ready to link up with the main effort as they exited Mamasapano. It was, as the police described it, a way-in, way-out, by-foot, night-only infiltration.

This was not the first operation in pursuit of Marwan. Nine operations had been attempted since 2010. Five were aborted. Another 4 had failed.

This time, for Exodus, a new element was added to the operational plan. It was a coordination strategy that timed the release of information about the operation to the moment of the main effort’s arrival at the target area.Nobody outside the SAF planners would know, not even the current police director.

The former SAF director gave the coordination strategy a name.

He called it “time on target."

Coddlers of terrorists

Getulio Napeñas, 55, is a graduate of the Philippine Military Academy class of 1982. By his own accounting he has two master's degrees and a Level 7 Executive Diploma on Strategic Leadership from the United Kingdom. He has undergone the Special Action Force Ranger Course, followed by the Urban Counter Revolutionary Warfare Course, and has taken specialized intelligence courses in London and Arizona. He also read aloud every course he attended under the Anti-Terrorism Assistance Program of the US State Department – Integrating Counter-terrorism Strategies at the National Level, Police Leader’s Role in Combating Terrorism, Senior Level Crisis Management and Vital Installation Security.

“I can look at anyone, and I mean anyone,” he tells the Senate, “and tell him face to face that I worked my way up the ladder not because of my connections but because of my performance, perseverance, dedication, credibility and dignity and integrity.”

Napeñas, whose head with its bowl-cut bob jerks as he reads from his speech, does not trust the armed forces. He attributes aborted operations in pursuit of Marwan to the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP). Police say he “speculated that sensitive information and operational information” were “deliberately leaked” during major operations, had “lamented” that high value targets were “being coddled by the MILF, whose members had a lot of contacts within the AFP.”

Napeñas was already clear that he believed the MILF to be an enemy force. It appeared he considered the possibility members of the AFP were the enemy as well.

Prior warning to the AFP, Napeñas told the Senate, would mean “compromising the operations again.”

Napeñas’ time-on-target (TOT) is new coordinating parlance for both the PNP and the AFP. It is not part of any established protocol, and has had no application in previous field operations. According to the BOI, based on interviews with involved SAF personnel, their understanding of time on target coordination was shaky at best.

Napeñas said he was not alone in approving the strategy. He said he presented his “new concept of operations” to President Benigno Aquino III at a meeting attended by former PNP chief Alan Purisima.

“Based on the records,” said a report by the PNP Board of Inquiry, “Oplan Exodus was approved by the President and implemented by suspended CPNP Purisima and other suspended PNP officers, to the exclusion of the Officer-in-Charge of the Philippine National Police Leonardo Espina.”

The best of friends

To understand Mamasapano means understanding the odd strength of the President’s loyalty to Alan Purisima. Purisima is the old friend, the shooting buddy, the large man with the cherubic face who protected the young Aquino from the bloody coups of the 1980s. On the day Alan Purisima was charged with graft in 2014, he was the director of the Philippine National Police, and the only 4-star general in the service.

When the complaints first went public, the President said Purisima was neither luxurious nor greedy. When Purisima offered to resign more than a week after the Mamasapano encounter, the President said it hurt to accept his resignation.

“Nothing,” Aquino once said, “can compare to our friendship.”

It was Purisima who had been briefed about Napeñas’ new operational plan, who had escorted Napeñas to the Palace to brief the President, who had continued to “listen” and “advise” and “suggest”– all while he was on preventive suspension at the orders of the Office of the Ombudsman.

Six weeks after he discovered the failure of Operation Plan Exodus, Benigno Aquino III, President of the Republic, Commander-in Chief of the Armed Forces of the Philippines, stood on a podium and informed the nation that he had no responsibility over the deaths of 67.

Even before a public investigation had concluded, the President offered a culprit, one Getulio Napeñas, who was relieved of duty the day after Mamasapano.

The accusations the President levelled against Napeñas were immense. Failure to plan. Failure to coordinate. Failure to abort. Failure to report the situation truthfully and well. Failure, most of all, to follow the direct orders of his commander-in-chief.

“Maybe the most generous way of looking at it is that there’s a lot of wishful thinking from Napeñas as opposed to reality. But it’s clear to me – he misled me. Now, what is my responsibility at this point in time? There’s a saying, fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me.’”

'Advice'

Yet it is not the first time during Operation Exodus that the President played the fool. He believed Napeñas and Purisima when they presented a plan that did not consider terrain, timing, and ground support. He believed the veracity of mission updates sent by Purisima throughout January 25. He believed that excluding the legal head of the PNP in favor of his good friend was proper procedure. He believed, and continues to believe, that he has no responsibility as the President of the Republic.

When his beliefs were questioned, he said he was misled and deceived. The plan, he said, appeared “thorough” when he approved it.

“Oplan Exodus can never be executed effectively because it was defective from the very beginning,” read the PNP Board of Inquiry (BOI) report. “Troop movement was mismanaged, troops failed to occupy their positions, there was lack of effective communication between the operating troops, command and control was ineffective, and foremost, there was no coordination with the AFP and peace mechanism entities.”

It is not clear who approved time on target coordination.

Aquino said he ordered Napeñas to coordinate with the AFP.Napenas said Purisima ordered him not to coordinate.

Purisima said his directives were advice, not orders.

On January 25, 2015, because of a new coordination strategy that may or may not have been approved, and a plan that may or may not have been complete, the commandos of the Special Action Force were ordered to execute a mission without a commitment of support from the armed forces.

They entered an armed enclave without understanding the terrain, without advice from the ceasefire committee, without the knowledge of both local and national police chiefs, and under the supervision of a suspended police general and a President who turned off his phone as troopers walked to their death.

The 24-hour exception

Mama Dagadas woke to gunfire past 4 in the morning of January 25. He picked up his M16 and left for a clearing behind a stand of coconut trees. He was not in any particular hurry. The clearing, situated behind a cornfield below the Tukanalipao footbridge, was the meeting place for the MILF living in Tukanalipao, whose operating procedure was to gather at the sound of gunfire.

The Bridge of BarangayTukanalipao

The bridge was where most of the Special Action Force troopers were killed

in an attempt to get top terrorist Zulkifli bin Hir alias Marwan.

Dagadas had joined the MILF when he was 20, along with almost every young man he knew. He was a tall, spare man with a long face, the son of a farmer who had made it to 6th grade and had no further ambition beyond pulling in the next harvest. He was married at 36, and was the father of a 3-year-old boy named Maher.

The rebels came, one by one, cousins and friends. There had been gunfire, and gunfire meant they had to gather and wait for the commander to cut across the town proper, cross the footbridge, walk across the cornfields and tell them what to do.

What they did not know was that in front of them, under the corn, waited the 55th Special Action Force. The 55th had been attempting to reach their assigned waypoint when they heard gunfire from Pidsandawan. They took over the cornfields at the bottom of the Tukanalipao footbridge to protect the 84th’s exit.

It was a location that provided concealment, not cover.

Napeñas radioed an order for the 55th to stand their ground and engage the enemy.

"If you identify them as the enemy and if they armed, do not let them come close. Engage."

About a dozen fighters from the 105th Base Command of the MILF were crossing the footbridge to the cornfield when two of their men were shot down.

“That was when we joined in,” Dagadas said.

PO2 Christopher Lalan, lone survivor of the 55th Special Action Company, said it was the MILF who shot first.

It was 5:20 in the morning. By 5:30, the SAF were pinned down by an enemy that “peppered them with heavy gun-fire, rocket-propelled grenade, and M203 grenades from different directions.”

Mama Dagadas may or may not have killed before, but he certainly tried his best that Sunday morning, when he crouched at dawn among the coconut trees and shot at the enemy hiding in the cornfields of Tukanalipao, Mamapasano, Maguindanao.

“We couldn't see the people there because there were corn plants,” he said. “They were under the corn. We didn't know who we were fighting. We hadn't seen them yet.”

The encounter lasted hours. Reinforcements arrived from the BIFF. Bullets ran out. Radios failed. Ordnance refused to fire. The last to send a message, SAF radioman Senior Inspector Ryan Pabalinas, died with 16 gunshot wounds to the body.

It ended at one in the afternoon. The 55th SAF had gone silent,

Operation Plan Exodus may not have had abort criteria, but there were two mitigating actions built into the plan in case of heavy fire – artillery support from the AFP and an immediate ceasefire by the peace panel.

Two mechanisms were part of the Agreement on the General Cessation of Hostilities: the Ad Hoc Joint Action Group (AHJAG) and the Coordinating Committee for the Cessation of Hostilities (CCCH).

Each mechanism has government (GPH) and MILF components. The joint AHJAG coordinates between government forces and the MILF to facilitate law enforcement operations. The joint CCCH responds to hostile and armed confrontation. Its mandate is to prevent and de-escalate conflict.

The protocols were an attempt to avoid armed men from shooting first and asking questions later. The questions were to be answered before they were asked, the allies named before the guns spat fire.

Among the many debates during the Senate inquiry was Napeñas’ insistence that the SAF did not violate ceasefire mechanisms put in place after the beginning of peace process negotiations.

Napeñas quoted the 2002 Joint Communiqué signed in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, by the MILF and the Philippine government.

“Except for operations against high priority targets,” read the agreement, “the AHJAG is required to inform the GPH and the MILF CCCH at least 24 hours prior to the conduct of the AFP or PNP operations” to allow for the evacuation of civilians and to avoid armed encounters.

It is on the 24-hour clause that Napeñas bases his choice to use TOT coordination.

“There is a exception in this part, Your Honor, that this is a high value target being pursued by the Special Action Force, sir, at this time.”

Napeñas was correct there was an exception, but failed to note that the clause “the AHJAG is required to inform the GPH and MILF CCCH” did not refer to the police or armed forces. The 24-hour exception allows the GPH-AHJAG, in cases of law enforcement operations with high value targets, to determine how much time, if at all, will be given to the GPH-CCCH and MILF-CCCH to prepare.

Had Napeñas chosen to read the revised implementing rules signed on July 23, 2013 by AFP Chief of Staff Emmanuel Bautista, Purisima, and Peace Panel Chair Miriam Coronel-Ferrer – an agreement that “provides for the amendment of all policies and other guidelines” – he would have discovered the specific demand the communiqué makes on all government forces.

Phase 1, which covers the preparation period before law enforcement operations, requires that “GPH forces” – the police and armed forces – to “communicate to the GPH-AHJAG of an impending law enforcement operation at least 24 hours prior.”

There are no exceptions to this clause.

The war room

In the coordination matrix Napeñas presented to the Senate, time on target notification would rest on himself as SAF Director.

The operational plan for Exodus marked 4 parties that required immediate notification at TOT – the AFP’s 6th Infantry Division (6th ID), the 1st Mechanized Brigade (1st MIB), the AJHAG and the CCCH.

Following Napeñas definition of time on target, notifications should have been released at 4 am, immediately after the 84th Seaborne reached Marwan’s hut in Pidsandawan.

Of the 4 parties in the coordination matrix, the SAF informed 3, more than a full hour after time on target.

The 6th ID’s Commander, Major General Edgardo Pangilinan, was sent a message at 5:06 am. He saw it at 6 am.

The 1st MIB’s Commander, Colonel Gener Del Rosario, was sent a message at 5:20 am. He saw it at 6:19 am.

The GPH-AHJAG Chair, Brigadier General Manolito Orense, received a phone call from Napeñas at 5:38 am.

The CCCH were not notified.

The first messages were variations on the same theme: the PNP-SAF was entering Mamasapano to serve warrants of arrest to high value targets with the support of the Maguindanao Provincial Police Office.

“For your info, on January 25, 2015 at about 0230H, PNP-SAF supported by MagPPO PRO ARMM shall be conducting LEO and serve WA against HVTS in Mamasapano, Mag.”

The messages said that coordination “was also done” with the 6th ID, the 45th IB and the 1st Mech.

In the next hour, the commanding officers under the Western Mindanao Command, while fielding calls from their own superiors, attempted to confirm the details of what they initially understood was a coordinated law enforcement operation.

The results painted a picture.

The Commander of the 601st Infantry Battalion said he had “no knowledge.”

The Police Director of the Maguindanao Police Provincial Office said “negative.”

The Commander of the 6th ID said he had just seen a text message, but knew nothing more.

The Commander of the 1st Mechanized Brigade checked his phone and found an earlier text message.

The Commander of the 45th Infantry Battalion responded with “no coordination.”

The earliest actual contact Napeñas made with the parties in the coordination matrix was 5:38 am, when Orense answered Napeñas’ call.

By then, the 36 troopers of the 55th SAC had already engaged the enemy. Only one would survive.

'Ceasefire them'

It was the MILF who warned the CCCH at 6:38 am. The message was sent to CCCH-GPH Chair Brigadier General Carlito Galvez and Major Carlos Sol, Head of Secretariat of the Committee on the Cessation of Hostilities. Both were still in Iligan on a decommissioning mission.

“Salam bro,” the message from MILF-CCCH Chair Rashid Ladiasan. “Firefight erupted between the AFP and the 105BC at Tukanalipao, Mamasapano. The AFP troops moved in without any coordination and this is difficult to control to avoid encounters between our forces when there is no coordination. This is clearly disregarding and violating the ceasefire. Now with that situation the only option is to ceasefire otherwise it will escalate further.”

For half an hour they made the calls. 1st Mech. The 601st Brigade. The 6th ID. All units near Mamasapano.

The AFP said they had no engaged units. Nobody knew, said Sol. There was no sense of anything, no suspicion.

By 7:30 am, they were told it was the SAF.

Sol received a call from Police Superintendent Odelio Jocson, Police Director of the Maguindanao Provincial Police.

“He asked me, ‘Bok, did you hear what’s happening in Mamasapano?’ I said, “I heard there was shooting between army and the 105th.’

Jocson told Sol that it wasn’t the army. It was SAF.

“I said, ‘Sir what’s that, is that yours? Is that coordinated?’

He said, “I don’t know, I don’t know, I’m in Manila, but Bok, just help them. Just ceasefire them.”

“That was a Sunday,” remembers Sol. “Our people were Catholic, they were in Church. I had them pulled out from the churches. One of my people was in the grotto attending Mass. It took a while to contact him, when we got to him, he said, “'Sir, I’m in church, I’ll just finish.’ I told him to get out.”

'32 KIA'

Carlos Sol was born and raised in Cotabato. His father was a soldier. His brother was a soldier. Sol himself was an infantryman from the 27th IB, a big man with a lived-in face whose relationship with the MILF survived even after their discovery that he was an army intelligence operative. Sol was the man both sides trusted, whose worth as a negotiator had been proven again and again.

That morning in January 25, while he and Galvez were racing back to Maguindanao, Sol was fielding calls from contacts in the MILF. The base commands were confused. Commander Bravo was getting ready to attack in Lanao. Basilan was asking if the peace process was over. The rebels thought war had broken out.

Sol had very few answers. What was important, Sol said, was for the CCCH to get between the two parties and physically separate them. In close encounters, it was nearly impossible. Sol arrived too late to join the crisis team attempting to enter the site.

Galvez went to the Tactical Command Post, Sol went to Tukanalipao to monitor the situation.

“The crisis team attempted to get in the middle, but they couldn’t penetrate,” Sol said. “The shooting was intense. So if you saw the ceasefire crisis team, they were there, hiding behind the bananas, even if they knew the bullets were going through. The psychology was that, ‘We have to go in.’”

He got a message at 3:30 in the afternoon. His boys – the ceasefire committee team – had penetrated the area. The report was 32 dead.

Sol called Galvez.

“Sir, 32, 32 are KIA. How many are we looking for?”

“General Napeñas is here,” said Galvez.

“Sir, 32 KIA. How many troopers are we looking for?”

Napeñas answered, “32, Bok.”

“Okay sir, accounted. We won’t look for anyone anymore. We’ll just organize a retrieval team.”

“He didn’t say anything else,” remembers Sol. “He didn’t correct me.”

At 5:20 in the afternoon, while Sol and the CCCH were organizing the retrieval of the corpses of the 55th SAC in Tukanalipao, there was a phone call from General Galvez.

“Check with the boys,” he said. “They say there’s one more platoon.”

“How many are there left sir?”

“They say there’s more,” Galvez said. “I don’t know how many more.”

It was 13 hours since time on target. The bodies were already being collected.

It was the first time Galvez, Sol, or anyone in the AFP were told that there was another SAF team in Mamasapano – the 84th Seaborne, still fighting for their lives under heavy fire.

It would be 11:30 in the evening when the 84th would finally be rescued from a running gun battle that lasted more than 17 hours.

Danger close

The operational plan for Operation Exodus offered two mitigating actions in case of heavy fire – artillery support from the AFP, and an immediate ceasefire headed by the CCCH.

Both demanded specific and prior coordination.

Although the PNP’s BOI report concedes the efforts of the CCCH to enforce the ceasefire, the armed forces is held responsible for the choice to withhold indirect fire.

“Such support,” read the report, “was not delivered when needed.”

The Directive on the Deployment of the Howitzer, issued by the Army Artillery Regiment, lists 3 elements necessary before the firing of artillery: the deployment of forward observers, direct communication with the field artillery battery, and the identification of enemy forces from friendly forces.

The last direct communication with the 55th SAC was at 7 am.

At 7:30 am, according to testimony to the BOI, the PNP requested for artillery fire and offered coordinates. Commander Gener Del Rosario of the 1st MIB asked the PNP for the locations of engaged troops, armed men, forward and tail elements, as well as civilians.

The questions could not be answered.

At 8:39 am, Napeñas sent Del Rosario his answer.

“Gener, good am. This is the location, many enemies GC 688663. Request indirect fire. There are no civilians since earlier.”

At the time, a single civilian was already embedded with the SAF troop – Badruddin Langalan, a farmer in his early-20s who had crossed the Tukanalipao bridge at dawn to charge his cell phone. The SAF had snatched him from his bicycle and tied his arms behind him to ensure operational security.

On the Senate floor, AFP Chief of Staff Gregorio Catapang defended the choice to withhold fire.

“We need to know where the enemy is, where the troops are, and we need a forward observer so that when we drop the bomb, we know what the impact will be on the enemy. It’s happened in the past that even if we knew where the enemy was, even when we knew where our troops were, there was still friendly fire.”

Interior Secretary Mar Roxas said it was a risk that should have been taken.

“To my mind,” he told the Senate, “there is the concept of ‘fire on my location.’ We’re being overrun, they will finish us off. We will take our chances that you fire on our position because at least there is a chance that we won’t be hit and you’ll hit the enemy. It’s better than you not firing, because we will all die here.”

The blast radius of a 105 mm high explosive round shot from a 105 mm howitzer is 50 meters in all directions. Had the commander of the 6th Infantry Division of the AFP decided to fire on the grid coordinate sent by Napeñas at 8:39 am, a coordinate that may or may not have moved in the almost two hours since it was sent to him by Pabalinas, every man, woman and child within 100 meters would have died in the blast, including lone survivor PO2 Christopher Robert Lalan, who lived to tell the tale.

'We could have saved them'

It is 10 in the evening. The building has emptied. A single security guard sits slumped on a couch in the lobby. Major Carlos Sol is using his coffee cup, a teaspoon and a pen to illustrate the ground conditions in Mamasapano on January 25.

He moves the coffee cup. This is Tukanalipao, he says.

He lays the pen horizontally, behind the cup.

“This is the road.”

The teaspoon goes in front of the cup, perpendicular to the pen.

“This is the bridge.”

He points to the cup.

“This the community. Even when the trucks came, the people knew the SAF were there, but they didn’t know who they were. It’s the MILF’s SOP for all of them to cross the bridge. They have an area here, behind the cornfield, where they withdraw to establish a defensive position because they’re avoiding the forces here. The automatic reaction for the MILF is not to engage, but avoid. They didn’t even know there were people in that cornfield.”

Sol is willing to understand time on target coordination. He is even willing to understand fears that telling the CCCH would compromise operational security. What he does not understand is why they were not told when it mattered.

“When they were able to take down Marwan that means the mission is already compromised. There was a firefight in that area of Pidsandawan, their presence was already compromised, operational security was no longer significant as far as compromise is concerned.”

The 84th had neutralized Marwan at 4:15 am.

“At the time, the 55th SAC had no casualty yet,” said Sol. “There was lead-time. But the SAF hid it.”

The fighting in Tukanalipao between the MILF and the 55th SAC blocking force began at 5:20 am.

“If they told us at 4:30, even 4:35 or let’s say 4:40, if they told that there are troops in Pidsandawan and they had gotten Marwan, they were withdrawing through Tukanalipao, we could have called up the MILF CCCH.”

Sol believes that in the hour between time on target and the gunfire in Tukanalipao, the CCCH could have stepped in to avert the crisis. It had been done before, on many occasions, including an operation 3 weeks after Mamasapano, when the AFP went after the Abu Sayyaf in Basilan. The CCCH gave warning the same morning of the operation. The army passed through a route within sight of the MILF. There was no encounter.

To coordinate after guns blaze has a price – time. It takes at least 6 hours to enforce a ceasefire after an encounter begins. It was a luxury the 55th SAC did not have.

“We could have called the MILF. We could have told them, ‘You have troops in Tukanalipao, there’s government force withdrawing from Tukanalipao, tell your people to open a passageway so they can pass.’ It could have saved them!

“Them” is the 55th SAC.

Time on Target

Had the SAF troopers been ready for the terrain, they wouldn’t have miscalculated the travel time. Had they managed to occupy their positions, they wouldn’t have been forced to engage in daylight. Had the President involved the chief of the PNP instead of a suspended director, approval for TOT could have been stopped. Had Napeñas trusted the high command of the armed forces, they could have embedded their own forward observers and radio operators into the SAF platoons and prepared for artillery fire.

Had Purisima’s reports been accurate instead of reassuring, the President could have ordered urgent action. Had the planners had even a rudimentary understanding of the coordinating protocols of the peace process, the AHJAG could have been ready for an encounter without alerting the MILF. Had Napeñas coordinated at time on target, the CCCH could have attempted to keep the MILF away from the 55th SAC.

It is difficult to accept that some failure to coordinate can lead to the blood of 44 policemen splashed across a cornfield south of the country. The Senate calls it a massacre. The MILF call it a misencounter. The President says it wasn’t his fault.

The facts are these: policemen are dead, wives have been widowed, children have been orphaned and the peace process is a casualty. In total, 67 Filipinos were killed in Mamasapano, Maguindanao, including an 8-year-old child named Sarah who cowered in her backyard before dawn on January 25.

Perhaps some of them would have lived had there been coordination. But coordination is an innocuous word. Its associations are inoffensive, the crack of its consonants do not pulse with necessity. Coordination doesn’t kill, but perhaps ego can.

– Rappler.comEditor's note: All quotations in Maguindanaoan and Filipino have been translated to English

Mamasapano : Time on Target

http://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/in-depth/87410-mamasapano-time-on-target

*************************************

FULL TEXT: Executive Summary of PNP Board of Inquiry Report on Mamasapano Clash

Published below is the full text of the Executive Summary of the Philippine National Police Board of Inquiry Report on the Mamasapano clash, which claimed the lives of more than 60 people, including 44 members of the PNP's elite Special Action Force.

On January 25, 2015, sixty-seven (67) Filipinos died in Mamasapano, Maguindanao as a result of an encounter triggered by operation Plan (Oplan) Exodus.

The goal of Oplan Exodus was to neutralize high value targets (HVTs) who were international terrorists—i.e., Zkulkifli Bin Hir/Zulkifli Abhir (Marwan); Ahamad Akmad atabl Usman (Usman); and Amin Baco (Jihad).

Forty-four (44) members of the Special Aciton Force (SAF)—considered as the elite unit of the Philippine National Police (PNP) against terrorism and internal security threats-lost their lives in Mamasapano, while sixteen (16) other SAF members sustained severe injuries.

The tragic incident in Mamasapano raised several questions. How could a group of elite forces be massacred? Who was responsible for their deaths? What caused the traffic encounter in Mamasapano? Who were the hostile forces encountered by the SAF troops?

The Board of Inquiry (BOI) was created by the Philippine National Police (PNP) primarily to investigate the facts regarding Oplan Exodus and to provide recommendations in order to address such possible lapses.

The methodology used by the BOI in preparing this report is described in Chapter 1.

The BOI notes that the information obtained from certain key personalities were limited. For instance the BI failed to secure a interview with the President Benigno Aquino III, suspended Chief PNP (CPNP) Alan Purisima, Chief-of-Staff AFP (CSAFP) General Gregorio Catapang, and Lieutenant General Rustico Guerrero. All concerned officers of the Armed Fores of the Philippines (AFP) refused to be interviewed by the BOI despite repeated requests.

The BOI did not have access to other crucial information such as contents of Short Messaging System (SMS) or text messages, and logs of calls and SMS. BOI's requests for the submission of cellular phones for forensic examination were also denied by CSAFP Catapang, Guerrero, suspended CPNP Purisima and AFP officers. However, the sworn statement of suspended CPNP Purisima included a transcript of his SMS exchanges with the President on January 25, 2015.

Despite the foregoing limitations, the BOI succeeded in conducting several interviews, obtaining various types of evidence, processing and reviewing hundreds of documents, and conducting ocular inspection in Mamasapano to produce this Report.

Based on the records, Oplan Exodus was approved by the President and implemented by suspended CPNP Purisima and the Director of SAF (Napeñas) Getulio Napeñas, to the exclusion of the Officer-in-Charge of the Philippine National Police (OIC PNP) Leonardo Espina, who is the concurrent Deputy CPNP for Operations.

On December 16,2014, the OIC-PNP issued a Special Order No. 9851 which directed suspended CPNP Purisima and other suspended PNP officers, to “cease and desist from performing the duties and functions of their respective offices during the pendency of [their respective cases filed by the Ombudsman] until its termination.”

Napeñas and suspended CPNP Purisima ignored the established PNP Chain of Command by excluding OIC-PNP Espina in planning and execution of Oplan Exodus. Napeñas and suspended CPNP also failed to inform the Secretary of the Interior and Local Government (SILG) Mar Roxas about Oplan Exodus, and made no prior coordination with the AFP. Based on the records. SILG and OIC-PNO were informed of Oplan Exodus through a phone call by suspended CPNP Purisima at 05:50 a.m. on January 25, 2015. SILG learned about the operation when he got an SMS from Police Director Charles Calima Jr. at 07:43 a.m. on January 2, 2015.

The participation of the suspended CPNP in Oplan Exodus was carried out with the knowledge of the President. Records revealed instances when the suspended CPNP met with the President and Napeñas to discuss Oplan Exodus on January 25, 2015.

Records also show that suspended CPNP Purisima failed to deliver his assurances to coordinate with the AFP. At a crucial stage of the crisis, the suspended CPNP Purisima provided inaccurate information from an unofficial source, which further jeopardized the situation of the 55th SAC and 84th Seaborne in Mamasapano.

There are indications that Napeñas may not have considered differing opinions raised by his subordinate commanders. The mission planning appears to have been done by a group of officers and not by a planning team, with inputs heavily influenced by Napeñas. Subordinate commanders expressed that Napeñas had unrealistic planning assumptions such as the swift delivery of artillery fire and the immediate facilitation of ceasefire.

Napeñas chose to employ a “way-in/way-out, by foot and night-only” infiltration and exfiltration Concept of Operation (CONOPS) for Oplan Exodus. During an interview with BOI, Napeñas admitted that he expected casualty of around ten (10) SAF Commandos to accomplish the mission.

Napeñas also admitted that key variables for the success of Oplan Exodus, such as the coordination with the Sixth Infantry Division (6ID), and with the Coordinating Committee o the Cessation of Hostilities (CCCH) and Ad Hoc Joint Action Group (AHJAG) were not thoroughly considered in the mission planning. The established protocols and Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) of the AFP, CCCH and AHJAG in providing reinforcement and effecting ceasefire were not sufficiently discussed.

Napeñas proposed to the President the adoption of the time “Time-On-Target” (TOT) concept of coordination for Oplan Exodus. Application for the TOT concept restricted disclosure of information to a limited number of persons until the target is engaged. It appears that Napeñas' primary consideration for adopting the TOT concept was operational security (OPSEC) to reduce the risk of having Oplan Exodus compromised.

The records show that when the President gave instructions to CPNP Purisima and Napeñas to coordinate with the AFP, Napeñas raised his concern that the AFP might be compromised due to intermarriages of some AFP personnel with the local people. He cited previous SAF operations against the same HVTs that were coordinated with the AFP. Suspended CPNP Purisima and Mendez shared the qualms of Napeñas.

When Napeñas proposed to the President the adoption of the TOT concept for Oplan Exodus, the President remained silent.

Police Superintendent Raymund Train of the 84 SAC (one of the survivor from the Mamasapano encounter) attested that, in case of heavy enemy fire, the first planned mitigating action for Oplan Exodus was indirect artillery fire support from the AFP. The second planned mitigating action was the commissioning of the peace process mechanisms to facilitate ceasefire.

However, Napeñas failed to consider the consequences of the TOT concept vis-a-vis the required mitigating actions. He appeared to have relied heavily on the verbal commitment of the suspended CPNP Purisima to arrange for the needed AFP support. Coordination with the 6ID and CCCH and AHJAG was planned to be made at TOT, that was, upon engagement of the target. There was no plan for close air support.

With respect to the peace process mechanisms as mitigating actions in Oplan Exodus, the required coordination to trigger such mechanisms (such as a ceasefire) were not followed.

Prior communication with Brigadier General Carlito Galvez could have informed Napeñas that, in past experiences, a ceasefire could only be achieved after at least six (6) hours of negotiation.

By the time the AFP was informed about Oplan Exodus, a hostile encounter between the SAF Commandos and various armed groups in Mamasapano had already ensued.

Considering that the CONOPS adopted the way-in/way-out-in/way- that the CONOPS adopted heavy support from other SAF Commandos to secure the withdrawal route of the Main Effort (Seaborne). The plan was for the 84th Seaborne to link-up with 55th SAC and progressively with 4SAB units along the withdrawal route.

The delay in movement of the Seaborne affected the movement of the 4SAB and other reserve forces. When the containment and reserve forces arrived at the Vehicle Drop-off Point (VDOP), the situation in the area of operation was already hostile. Heavy sound of gunfire were heard coming from the location of the 55th SAC. The troops immediately disembarked, organized themselves and rushed to their designed waypoints (WP). Midway between WP8 and WP9, the reinforcing troops came under heavy enemy fire. The exfiltration route became dominated by hostile forces. The Ground Comander at the Advance Command Post (ACP) was not able to maneuver the troops to break enemy lines and force their way to reinforce the 55th SAC Commandos near WP12. Ineffective communication system further exacerbated the situation.

During the site survey in Mamasapano on February 24, 2015, the BOI took note of the unfavorabe terrain faced by the reinforcing troops. The wide terrain between their location and that of the 55th SAC was literally flat without adequate cover and concealment. Tactical maneuvers, such as the “Bounding Overwatch” technique, would have been difficult and may result to more casualties. According to the platoon leaders, enemy fires were coming from all directions which prevented them from maneuvering and reinforcing 55th SAC.

In a joint interview with BOI, Mayor Ampatuan of Mamasapano and the Barangay Chairman and Officials of Tukanalipao in Mamasapno claimed that in the past, armed elements would readily withdraw from the encounter side whenever white phosphorus rounds were delivered by Field Artillery Batter of the 6ID PA.

In an interview with BOI, Napeñas claimed that the 6ID immediately provided artillery fire support when one of its infantry company was harassed by armed elements sometime in late November or early December 2014.

However, during the execution of Oplan Exodus, three (3) white phosphorous rounds were delivered late in the afternoon and not earlier in the morning when such rounds could have mattered most to the 84th Seaborne and the 55th SAC.

SAF coordinated and requested for indirect artillery fire support from the 1st Mechanized Brigade as early as 07:30 a.m. The Brigade Commander of the 1st Mech Brigade, Colonel Gener Del Rosario sought clearance for artillery fire from the 6ID Commander, Major General Edmundo Pangilinan. Howver, of the three recommendations given by Col. Del Rosario, only the dispatches of infantry support and mechanized support were approved by the MGEN Pangilinan. The request for indirect artillery fire was put on hold since, according to Pangilinan, they still lacked details as mandated by their protocol.

Based on the records, MGEN Pangilinan took it upon himself to withhold artillery fire support in consideration of the peace process and artillery fire protocols. However, pursuant to AA, PA SOP No. 4, that decision could have been made by a Brigade Commander like Col. Del Rosario.

The primary objective of Oplan Exodus to get the HVTs was not fully completed. Two of its targets, Jihad and Usman, were able to escape and remain at-large.

Three hundred ninety-two (392) SAF Commandos were mobilized for Oplan Exodus. Forty-four SAF members lost their lives in carrying out this mission. In discovering the facts that lead to such deaths, this Report stresses the importance of command responsibility: “A commander is responsible for what his unit does or fails to do.”

Related Stories :

Mamasapano - Time on Target

http://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/in-depth/87410-mamasapano-time-on-target

Read more: http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/720501/new-mamasapano-lead-eyed#ixzz3lf1YU9cT

Read more:

The US Embassy in Manila on Tuesday denied claims that an American serviceman was killed in the tragic Mamapasano raid on Jan. 25.

“There were no US service member casualties,” US Embassy spokesman Kurt Hoyer said in an e-mail.

Hoyer was reacting to reports attributed to the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) suggesting that American soldiers were involved in the botched raid in Maguindanao province in which 44 Special Action Force (SAF) commandos were massacred.

A video footage of the recovery of the fatalities in the raid purportedly showed a “Caucasian” among the fatalities. At least 18 Moro rebels were likewise killed in the SAF operation to take out Malaysian bomb maker Zulkifli bin Hir, alias “Marwan.”

“The operation was planned and executed by Philippine authorities,” Hoyer said. “The US government consults regularly with Philippine security forces on issues of mutual interest,” he said, adding that questions about the operation should be directed to the Philippine government.

Pls read more:

TAGALIGTAS: Mamasapano One Year After; a SAF documentary PART 1

FINDINGS:

1. Chain of Command

1. Chain of Command

The Chain of Command in the PNP was violated. The President, the suspended CPNP Purisima and the former Director SAF Napeñas kept the information to themselves and deliberately failed to inform the OIC PNP and the SILG. The Chain of Command should be observed in running mission operations.

For instance, the Manual for PNP Fundamental Doctrine,1 requires the Commander to discharge his responsibilities through a Chain of Command. Such Manual provides that it is only in urgent situations when intermediate commanders may be bypassed. in such instances, intermediate commanders should be notified of the context of the order as soon as possible by both the commander issuing the order and the commander receiving it.

With respect to Oplan Exodus, the Chain of Command in the PNP should have been: OIC, CPNP PDDG Espina (as senior commander) to Napeñas (as intermediate commander). PDG Purisima could not legally form part of the Chain of Command by reason of his suspension.

2. Command Responsibility

The principle of Command Responsibility demands that a commander is responsible for all his unit does or fails to do. Command Responsibility cannot be delegated or passed-on to other officers. Under the Manual of PNP Fundamental Doctrine, Command Responsibility "can never be delegated otherwise it would constitute an abdication of his role as a commander. He alone answers for the success or failure of his command in all circumstances."

Based on all records, Napeñas admitted that he has command responsibility with respect to Oplan Exodus.

3. Coordination

The TOT coordination concept, which limits the disclosure of information to only a few personnel, is applicable only to ordinary police operations. This concept however does not conform to the established and acceptable operational concepts and protocols of the PNP. Even AFP commanders asserted that the TOT concept is alien to the Armed Forces and runs counter to their established SOPs. Without coordination, following the AFP definition, support to operating units such as artillery or close air support is not possible since these entails preparations.

4. Operation Plan

Oplan Exodus was not approved by the OIC-PNP. Napeñas dominated the mission planning, disregarding inputs from his subordinate commanders on how the operation will be conducted. The concept of the way-in/way-out, by foot and night-only infiltration and exfiltration in an enemy controlled community with unrealistic assumptions was a high-risk type of operation.

5. Execution

Oplan Exodus can never be executed effectively because it was defective from the very beginning. Troop movement was mismanaged, troops failed to occupy their positions, there was a lack of effective communication among the operating troops, command and control was ineffective and foremost, there was no coordination with the AFP forces and peace mechanism entities (CCCH and AHJAG).

6. Command and Control

Command and control is critical to a coordinated and collaborative response to the Mamasapano incident. In Oplan Exodus, the SAF's TCP and ACP were plagued by failures of command and control from the very start especially in the aspect of communication. As Oplan Exodus unfolded, mobile communication devices was used as a primary mode of communication. However, these devices fell short of what were needed to relay real-time information and coordination of activities to and from the chain of command.

Radio Operators were assigned at the TCP one each for 84th Seaborne and 55th SAC. However, 55th SAC and 84th Seaborne lost contact during the crucial moments of executing Oplan Exodus. They had to rely on distinctive gunfire to approximate each other's location. Radio net diagram was provided but failed when radio equipment bogged down.

7. Logistics

Some of the ordinance for M203 were defective. Although there were sufficient rounds of ammunition for each operating troop, the overwhelming strength of the enemy caused the troops to run out of ammunition. The common Motorola handheld radios failed when submerged in water because these were not designed for military-type of operations. The battery life was short because of wear and tear.

8. AFP Response

Artillery fire support was factored in as one of the mitigating actions of the SAF. However, such support was not delivered when needed. In consideration of the peace process, AFP did not deliver the artillery fire support under the consideration of the peace process, and on the absence of compliance with the required protocol. AFP demanded prior coordination to enable them to react and deliver the requested support. Nonetheless, the AFP sent infantry and mechanized units to reinforce the SAF. White phosphorus artillery rounds were fired late in the afternoon. However, by then, all of the 55th SAC lay dead except for one who was able to escape.

Local PNP units wer not fully utilized to reinforce the SAF. The reinforcement from the local and Regional PNP units were not seriously factored-in during the mission planning process.

9. Peace Process

Officials of the CCCH and AHJAG, when tapped by AFP, did their best to reinstate the ceasefire between the SAF and MILF combatants. The participation of other armed groups such as the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF), private armed groups (PAGs), and other armed civilians in the firefight delayed the ceasefire.

10. United States (US) Involvement

The US was involved in the intelligence operations and medical evacuations. No US personnel/troops were involved in the actual combat operation. The US supported the operation by providing technical support to enhance monitoring of the troops on the ground.

They were also involved in the identification of Marwan through DNA analysis.

11. Post-Mission Actions

The report submitted by the PNP Crime Laboratory shows that around four (4) SAF commandos with fatal gunshot wounds (GSWs) to the head and at the mid-portion of the trunk were deathblows delivered by shooting at close-range. In other words, not all the forty-four (44) fatalities died during the actual firefight, but were literally executed at close-range by the enemy.

A total of 16 SAF firearms and one (1) cellphone were returned by the MILF. It was observed that some parts of the returned firearms had been replaced.

CONCLUSIONS:

Based on the foregoing, the following conclusions were drawn:

1. The President gave the go-signal and allowed the execution of Oplan Exodus after the concept of operations (CONOPS) was presented to him by Director of Special Action Force (SAF) Director Getulio Napeñas.

2. The President allowed the participation of the suspended Chief Philippine National Police (CPNP) Police Director General Alan Purisima in the planning and execution of the Oplan Exodus despite the suspension order of the Ombudsman.

3. The President exercised his prerogative to deal directly with Napeñas instead of Officer-in-Charge of the PNP (OIC-PNP) Police Deputy Director General Leonardo Espina. While the President has the prerogative to deal directly with any of his subordinates, the act of dealing with Napeñas instead of OIC-PNP Espina bypassed the established PNP Chain of Command. Under the Manual for PNP Fundamental Doctrine,2 the Chain of Command runs upward and downward. Such Manual requires the commander to discharge his responsibilities through a Chain of Command.

4. The suspended CPNP Purisima violated the preventive suspension order issued by the Ombudsman when he participated in the planning and execution of Oplan Exodus. He also violated the Special Order No. 9851 dated December 16, 2014 issued by OIC-PNP Espina, directing him and other suspended PNP officers to "cease and desists from performing the duties and functions of their respective offices during the pendency of the case until its termination."

5. In the same meeting where the President instructed Napeñas and suspended CPNP Purisima to coordinate with the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP),3 PDG Purisima thereafter said to Napeñas: "Ako na ang bahala kay Catapang." The PNP Ethical Doctrine Manual cites, "Word of Honor — PNP members' word is their bond. They stand by and commit to it." The statement of Purisima may be construed as an assurance of providing the coordination instructed by the President.

6. Suspended CPNP Purisima provided inaccurate information to the President about the actual situation on the ground when he sent text messaged to the President stating that SAF Commandos were pulling out,4 and that they were supported by mechanized and artillery support.5

7. Despite his knowledge of the suspension order issued by the Ombudsman, Napeñas followed the instructions of suspended CPNP Purisima not to inform OIC-PNP and the Secretary of the Interior and Local Government (SILG) Mar Roxas about Oplan Exodus. This violated the PNP Chain of Command.

8. Napeñas failed to effectively supervise, control and direct personnel which resulted in heavy casualties of the SAF Commandos. Under the Manual on Fundamental Doctrines, Command Responsibility means that a commander is responsible for effectively supervising, controlling and directing his personnel. Under that same doctrine, a commander is responsible for what his unit does or fails to do.

9. Napeñas followed his Time-on-Target (TOT) coordination concept despite the directive of the president to coordinate with the AFP prior to the operation.

10. The TOT coordination concept adopted by the SAF does not conform with the established and acceptable operational concepts and protocols of the PNP.

11. The protocols of the established peace process mechanisms, through the Coordinating Committee on the Cessation of Hostilities (CCCH) and Ad Hoc Joint Action Group (AHJAG), were not observed during the planning and execution of Oplan Exodus.

12. The mission planning of Oplan Exodus was defective due to: (1) poor analysis of the area of operation; (2) unrealistic assumptions; (3) poor intelligence estimate; (4) absence of abort criteria; (5) lack of flexibility in its CONOPS; (6) inappropriate application of TOT; and (7) absence of prior coordination with the AFP and AHJAG.

13. The following factors affected the execution of CONOPS: (1) mismanaged movement plan from staging area to Vehicle-Drop-Off Point (VDOP); (2) failure to occupy the designated way points; (3) ineffective communication system among the operating troops; (4) unfamiliarity with the terrain in the are of operation; (5) non-adherence to the operational/tactical Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs); (6) lack of situational awareness among commanders; and (6) breakdown in the command and control.

14. Artillery support from 6th Infantry Division of the Philippine Army (6ID-PA) was not delivered when needed most because Major General Edmundo Pangilinan, Division Commander of 6ID, considered the on-going peace process and protocols in the use of artillery.

15. The lack of situational awareness, limited cover and concealment, ineffective communication, and sustained enemy fire prevented the 1st Special Action Battalion (1SAB) and 4SAB containment forces from reinforcing the beleaguered 55th Special Action Company (SAC) troops.

16. CCCH and AHKJAG undertook all efforts to reinstate the ceasefire. "Pintakasi" and the loose command and control of the MILF leaders over their field forces contributed to the difficulty in reinstating ceasefire.

17. Some of the radios of the SAF Commandos were unreliable because these were not designed for military-type tactical operations. The batteries had poor power-retention capability due to wear-and-tear. Furthermore, SAF radios were not compatible with AFP radios for interoperability.

18. There was a breakdown of command and control at all levels due to ineffective and unreliable communication among and between the operating units.

19. There are indications that 55th SAC was not able to secure its perimeter, conduct reconnaissance, occupy vantage positions and establish observation posts.

20. Several rounds of ammunition of M203 grenade launchers were defective.

21. The United States involvement was limited to intelligence sharing and medical evacuation. Only SAF Commandos were involved in the actual combat operation of Oplan Exodus.

22. Autopsy reports indicate that four (4) SAF Commandos were shot at close-range while they were still alive. Records also indicate that possibility that some SAF Commandos were stripped-off their protective vests prior to being shot at close-range.

RECOMMENDATIONS:

Based on this Report's findings and conclusions, the Board of Inquiry (BOI) recommends the following:

1. Where the facts of this Report indicate possible violations of existing laws and regulations, appropriate government agencies should pursue the investigation of the Mamasapano incident to determind the criminal and/or administrative liabilities of relevant government officials, the MILF and other individuals.

2. The AFP and PNP, in coordination with OPAPP, should immediately review, clarify and strengthen the Join AFP/PNP Operational Guideline for Ad Hoc Joint Action Group especially in the area of coordination during Law Enforcement operations (LEO) against HVTs.

3. The AFP and PNP should jointly review related provisions of their respective written manuals and protocols to synchronize, reconcile and institutionalize inter-operability not only between these two agencies but also with other relevant government agencies. The National Crisis Management Core Manual (NCMC manual) could be one of the essential references.

4. Crisis management simulation exercises (similar to fire and earthquake drills) should be regularly conducted among key players including local government units particularly in conflict prone areas.

5. The PNP should review its Police Operational procedures to cover operations similar to Oplan Exodus and to clarify coordination issues.

7. The PNP should craft its own Mission planning Manual and institutionalize its application in PNP law enforcement operations.

8. The capabilities of SAF and other PNP Maneuver Units for Move, Shoot, Protect, Communicate and Close Air Support (CAS) should be enhanced.

9. The PNP should review its supply management system to ensure operational readiness of munitions and ordinance.

10. Cross-training between the PNP and the AFP pertaining to management and execution of military-type tactical operations should be institutionalized.

11. The PNP should immediately grant 1 rank promotion to all surviving members of the 84th Seaborne and PO2 Lalan for their heroism and gallantry in action, posthumous promotion to the fallen 44 SAF commandos, and should give appropriate recognition to all other participating elements.

Link for full BOI Report :

*******************************************************************

The Moro Islamic Liberation Front submits its final report on the Mamasapano incident to the International Monitoring Team, and provides copies to the government and the Senate, among others.

FULL TEXT: MILF report on Mamasapano

MANILA, Philippines – The Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) submitted its final report on the Mamasapano incident to the International Monitoring Team (IMT) on Tuesday, March 24.

The MILF also provided copies of the 35-page report to the government and the Senate, among others, days after the Senate released its final report on the bloody January 25 clash, and nearly two weeks after the police submitted its report to the PNP leadership.

The MILF accused the police Special Action Force (SAF) team of firing the first shots. It also said the MILF sustained the first casualties in the clash that killed 67 people, including 18 of its members, 44 elite cops, and 5 civilians in Mamasapano, Maguindanao. (READ: SAF used dead comrades as shields: MILF report)

It recommended filing charges against SAF survivor Police Officer 2 Christopher Lalan for allegedly committing war crimes and human rights violations. (READ: MILF: Charge SAF survivor for killing sleeping men, civilian)

The MILF has maintained that the government's failure to coordinate Oplan Exodus, the police operation against terrorists Zulkifli bin Hir or Marwan, and Abdul Basit Usman, led to the bloody clash.

The office of Senator Grace Poe, chair of the Senate committee on public order and dangerous drugs, released a copy of the MILF report to the media.

****************************************************************

Mourners of Mamasapnao

The cornfield of Mamasapano

President Pnoy Aquino (front left side) during the wake of Fallen SAF 44

Related Stories :

National Day of Mourning: PHL pays tribute to 44 fallen PNP-SAF men

http://www.gmanetwork.com/news/story/420448/news/nation/national-day-of-mourning-phl-pays-tribute-to-44-fallen-pnp-saf-men

Mamasapano - Time on Target

http://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/in-depth/87410-mamasapano-time-on-target

PNP Board of Inquiry report on Mamasapano encounter http://www.gmanetwork.com/news/story/451737/news/nation/full-report-pnp-board-of-inquiry-report-on-mamasapano-encounter

FULL TEXT: MILF report on Mamasapano http://www.rappler.com/nation/87812-full-report-milf-mamasapano

The Mourners of Mamasapano

They are the wives of dead rebels, the mothers of lost children, the women who watch the sky and wait for the mortars to fall. Welcome to Mamasapano, where the government’s terrorists are the men their people call heroes.

http://www.rappler.com/nation/mourners-mamasapano-milf-saf

Waterlilies (poem): Tribute to the Tragedy in Mamasapano

Waterlilies (poem): Tribute to the Tragedy in Mamasapano http://rightnow.ph/waterlilies/

SAF survivor kills unarmed rebels, civilian http://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/in-depth/84735-saf-survivor-kills-unarmed-rebels-mamasapano

SAF's Oplan 'Exodus' map came from Americans http://www.rappler.com/nation/89186-oplan-exodus-us-involvement-artillery?cp_rap_source=yml#cxrecs_s

TIMELINE: Mamasapano clash http://www.rappler.com/nation/82827-timeline-mamasapano-clash

More questions for Aquino, Purisima on 'Exodus' http://www.rappler.com/nation/83460-questions-aquino-purisima-mamasapano-hearing?cp_rap_source=yml#cxrecs_s

SAF officer tells army colonel: 'Man up, sir'

Related Youtube Videos

Nakaligtas

na SAF commando sa operasyon sa Mamasapano, idinetalye ang naganap

PNP-SAF

"The fallen 44 and the coward 300"

SAF

TROOPERS NA DI TUMULONG NOONG 'MAMASAPANO

ENCOUNTER,' NAKUNAN NG VIDEO

Ex-SAF

chief, nagsalita na; idinetalye ang operation plan sa teroristang si Marwan

SONA: SAF survivor, naglabas ng sama ng loob

Magpakailanman

March 14 2015 Tribute Mamasapano

"Fallen 44" Full Episode

***************************************************

Other Videos - Live fightings between SAF and MILF

(LIVE)PNP SAF VS MILF @ Maguindanao.( Live action)

Maguindanao clash between SAF and MILF (January 25,2015)

******************************************

New Developments on September 14, 2015

New Mamasapano lead eyed

Aquino: Alternative truth emerges; probe continuing

President Aquino on Tuesday revealed there was an “alternative truth” to the Mamasapano debacle, eight months after the bloody encounter that claimed the lives of police commandos, civilians and Moro rebels, and set back the passage of a Bangsamoro law that could have been his legacy. The President said the photo of Malaysian terrorist Zulkifli bin Hir, alias “Marwan,” showing him dead in his hut that came out in the Inquirer on Jan. 30 “posed many questions and that is what we want to resolve.”

The so-called alternative truth, “may have very serious unintended consequences. Lives are at serious risk,” said one Inquirer source who asked not to be named for lack of authority to talk on the matter.

Various other sources also told the Inquirer that the photograph raised more questions than answers for the government even as then police Special Action Force (SAF) commander, Director Getulio Napeñas, said the operation was a success because his men took down Marwan.

Among these were why Marwan was half-naked and how the SAF was able to take pictures from such an angle if there was a firefight going on.

Read more: http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/720501/new-mamasapano-lead-eyed#ixzz3lf1YU9cT

**************************

Was

torching of Marwan’s hut a cover-up as to who really killed the terrorist?

Was the

torching of Marwan’s hut meant to cover up the real circumstance behind the

killing of the Malaysian terrorist?

The hut that served as the hideout of Zulkifli Bin Hir, alias

“Marwan”, that was burned down after the Mamasapano clash could have been preserved

as a crime scene to prove that the Special Action Force (SAF) troopers indeed

killed the Malaysian terrorist.

Retired Police Director Getulio Napeñas, the former SAF director

who was relieved over the alleged mishandling of the operation, and sources

from the SAF community questioned the burning of the hut amid the recent

confusion over who really took down Marwan.

“The

hut of Marwan could have provided a crime scene where we could’ve gotten pieces

of evidence to further support our claim that SAF men shot Marwan,” Napeñas

said in a telephone interview with INQUIRER.net on Monday.Read more:

******************************

US denies soldier killed in Mamasapano

“There were no US service member casualties,” US Embassy spokesman Kurt Hoyer said in an e-mail.

Hoyer was reacting to reports attributed to the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) suggesting that American soldiers were involved in the botched raid in Maguindanao province in which 44 Special Action Force (SAF) commandos were massacred.

A video footage of the recovery of the fatalities in the raid purportedly showed a “Caucasian” among the fatalities. At least 18 Moro rebels were likewise killed in the SAF operation to take out Malaysian bomb maker Zulkifli bin Hir, alias “Marwan.”

“The operation was planned and executed by Philippine authorities,” Hoyer said. “The US government consults regularly with Philippine security forces on issues of mutual interest,” he said, adding that questions about the operation should be directed to the Philippine government.

*******************************

No comments:

Post a Comment