The moment of truth: Philippines vs. China at The Hague

By Richard Javad Heydarian, special for CNN Philippines

Updated 15:09 PM PHT Thu, July 9, 2015

The International Tribunal on the Law of Sea (ITLOS) at the The Hague, Netherlands

The week covering July 7 to 13 will be pivotal to the Philippines’ legal battle to assert its claims over the portion of the South China Sea, that it calls the West Philippine Sea.

Metro Manila (CNN Philippines) — The Philippines’ quest for peacefully resolving territorial disputes in the South China Sea has entered a critical stage. After more than two years of hard work and extensive preparations, culminating in the thousand-page-long memorial, Manila has the chance to convince the arbitral tribunal at The Hague that its case deserves to be heard.

The key hurdle, however, is the question of jurisdiction: That is to say, whether the Arbitral Tribunal, formed under the aegis of the UNCLOS, has the mandate to rule on the Philippines’ case against China. We won’t be able to even defend the merit of our case, unless we convince the court that compulsory arbitration is the way forward.

What is at stake is not only the merits of the Philippines’ arguments, and the questionable character of China’s sweeping claims, but also the very credibility and viability of international law as the primary arbiter for resolving seemingly intractable territorial spats. This is precisely why the whole international community is anxiously following the ongoing proceedings at The Hague.

A historic case

The Philippines has been praised by nations around the world, because it is the first country to have dared (under Art. 287 and Annex VII of UNCLOS) to take China to the court. Throughout my visits to and interactions with colleagues and officials from sympathetic countries across the Pacific region — and, I must say, there are many of them — I have constantly been told about how they genuinely admire our government’s decision to resort to compulsory arbitration despite China’s vehement opposition.

Though China has refused to engage the legal proceedings, claiming “inherent and indisputable” sovereignty over almost the entire South China Sea, the UNCLOS (under Art. 9, Annex VII) has not barred the resumption of our arbitration efforts, which kicked off in early 2013. Without a doubt, the Aquino administration has made a very bold decision by taking on China directly — albeit not through force, but instead the language of law.

Beijing knows it would be very difficult to justify its notorious nine-dashed-line doctrine, so it has instead chosen to sabotage the Philippines’ arbitration efforts by raising (see its Dec. 7, 2014 position paper, which can be read as an informal counter-memorial) technicality-procedural questions. China has deployed three related arguments that aim to put into question whether the arbitral tribunal should exercise jurisdiction at all.

China cites that the UNCLOS doesn’t have the mandate to address sovereignty-related (title to claim) questions, while, invoking Art. 298 back in 2006, China has opted out of compulsory arbitration on issues that concern its territorial claims, among others. China also claims that it is premature to resort to compulsory arbitration, since alternative mechanisms haven’t been fully exhausted. The Philippines’ savvy legal team, however, has tried to address the jurisdiction issue by eschewing the sovereignty question, instead focusing on two major issues.

The fog of law

First, the Philippines has emphasized the importance of clarifying (under Art. 121 of UNCLOS) the nature of disputed features: Whether they are low-tide or high-tide elevations or islands, since this has a huge implication on whether the features can be appropriated at all or can generate their own 200 nautical miles Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

Perhaps the most important argument of the Philippines’ is that the arbitral tribunal should examine (and hopefully invalidate) China’s nine-dashed-line claims, which are based on pre-modern, questionable, and vague notion of “historical rights/waters”. In short, we want to make sure all claimant countries harmonize their claims and maritime behavior along modern, internationally-accepted legal principles, not obscure doctrines.

The legal community is quite divided on whether the Philippines can overcome the jurisdictional hurdle, since it will have to argue that its case transcends any sovereignty-related question.

But practically everyone agrees that China has to first clarify sweeping territorial claims, which are neither consistent nor precise. Up to this day, it is not clear whether China is claiming the entire South China Sea or only the features and fisheries and hydrocarbon resources in the area. And if China doesn’t even clarify the precise coordinates of its claims, it would be almost impossible to have any viable joint development scheme among claimant countries.

The Philippines’ case has also presented a huge dilemma for arbitration bodies under UNCLOS. If the Arbitral Tribunal turns down jurisdiction, and refuses to even hear the merits of our arguments, then the very viability of international law as a conflict-management/resolution mechanism will come under question.

At the same time, if it decides to push ahead and eventually rule against China, then there is a huge risk that, as a good friend Columbia University Professor Matthew C. Waxman puts it, it would be "ignored, derided and marginalized by the biggest player [China] in the region." After all, there are no multilateral compliance-enforcement mechanisms to force China — a permanent member of the UN Security Council — to abide by any unfavorable verdict.

In practical terms, the big concern is that while the legal cycle slowly grinds, China is actually changing the facts on the ground on a daily basis. This is why it is extremely important that the Philippines remains vigilant, and primarily focuses on tangibly guarding its interests on the frontline by fortifying its position on features it already controls, negotiate necessary measures (i.e., hotlines) to prevent unwanted clashes and escalation in the high seas, and employ all instruments in its toolkit to protect its territorial integrity.

An urgent concern, in particular, is to prevent China from imposing an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) in the Spratly chain of islands, which may give Beijing the ability to choke off the supply-lines of other claimant states and dominate arguably the world’s most important maritime highways. The truth is that, we can’t only rely on UNCLOS to address this critical situation, and we will need the help of our allies and partners across the world as well as the full support of the Filipino nation.

http://cnnphilippines.com/news/2015/07/09/moment-of-truth-philippines-vs-china-the-hague-richard-heydarian.html

*******************************************

O n 22 January 2013, the Philippines formally conveyed to China the Philippine Notification and Statement of Claim that challenges before the Arbitral Tribunal the validity of China’s nine-dash line claim to almost the entire South China Sea (SCS) including a peaceful negotiated settlement of its maritime dispute with China.

China’s nine-dash line claim is contrary to UNCLOS and unlawful. The Philippines is requesting the Tribunal to, among others:

1. Declare that China’s rights to maritime areas in the SCS, like the rights of the Philippines, are

established by UNCLOS, and consist of its rights to a Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone

under Part II of UNCLOS, to an EEZ under Part V, and to a Continental Shelf under Part VI

2. Declare that China’s maritime claims in the SCS based on its so-called nine-dash line are

contrary to UNCLOS and invalid

3. Require China to bring its domestic legislation into conformity with its obligations under

UNCLOS; and

4. Require China to desist from activities that violate the rights of the Philippines in its maritime

domain in the WPS.

The Arbitral Tribunal has jurisdiction to hear and make an award as the dispute is about the interpretation and application by States Parties of their obligations under the UNCLOS.

The Philippines position is well founded in fact and law.

Annex VII Arbitration under UNCLOS

A rather unique feature of UNCLOS is that it allows, under certain conditions, a State Party to bring another State Party to arbitration even without the latter’s consent. This is allowed under Annex VII when States Parties are unable to settle a dispute by negotiation, third party resolution or other peaceful means.

An Annex VII arbitral tribunal is composed of five members free to determine its own procedure. The absence of a party or failure of a party to defend its case shall not constitute a bar to the proceedings. There have been four instances when States Parties have resorted to Annex VII arbitration: Bangladesh-India, Mauritius-UK, Argentina-Ghana and Philippines-China.

http://www.dfa.gov.ph/images/PDF/2013%20WPS%20Update%201%20-%20May%202013.pdf

http://www.dfa.gov.ph/index.php/west-philippine-sea-arbitration-updates

http://www.pca-cpa.org/showpage.asp?pag_id=1529

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Origin of China's Nine Dash Line

Justice Carpio debunks China’s historical claim

MANILA, Philippines–Panatag Shoal (Scarborough Shoal) has always been part of the Philippines that from the 1960s to the 1980s, Philippine and American planes used it as an impact range during joint military exercises.

And, according to Supreme Court Associate Justice Antonio Carpio, China or any other country never protested the bombing runs on the shoal.

China is claiming the resource-rich shoal off Zambales province as part of its territory, seizing it after a two-month maritime standoff with the Philippines in 2012.

China’s own maps

And, according to Supreme Court Associate Justice Antonio Carpio, China or any other country never protested the bombing runs on the shoal.

China is claiming the resource-rich shoal off Zambales province as part of its territory, seizing it after a two-month maritime standoff with the Philippines in 2012.

“If the Philippines can bomb a shoal repeatedly over decades without any protest from neighboring states, it must have sovereignty over [that] shoal,” Carpio said in a lecture at De La Salle University in Manila last Friday.

Carpio, who had been going around lecture circles questioning the legality of China’s claim to 90 percent of the 3.5-million-square-kilometer South China Sea, again took on China’s assertions in a lecture titled “Historical Facts, Historical Lies and Historical Rights in the West Philippine Sea.”

He said China was arguing that its extensive claim was based on “historical facts and international law.”

But historical facts, Carpio said, have “no bearing whatsoever in the resolution of maritime disputes” under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (Unclos).

China also cannot invoke ancient conquests and maps under international law to claim territories, he said.

China’s own maps

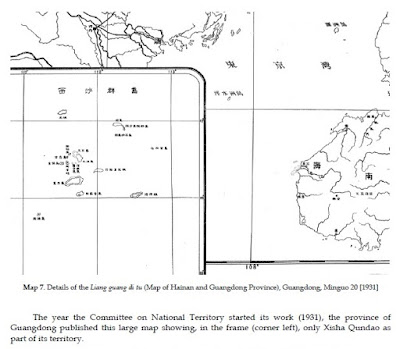

Carpio showed copies of maps of China dating back to the 13th century and to the 1930s, made by Chinese authorities or individuals and even foreigners, that showed the southernmost territory of China has always been Hainan Island and that Chinese territory never included the Spratly Islands in the middle of the South China Sea and Panatag Shoal in the West Philippine Sea.

“There is not a single ancient map, whether made by Chinese or foreigners, showing that the Spratlys and Scarborough Shoal were ever part of Chinese territory,” Carpio said.

He said China itself had been saying as late as 1932 that the southernmost part of Chinese territory was Hainan Island.

‘Gigantic fraud’

Carpio called China’s claim to almost the entire South China Sea, which Beijing calls “nine-dash line,” a “gigantic historical fraud” because it claims that its southernmost territory is James Shoal, which is 90 kilometers from the coast of Bintulu, Sarawak, Malaysia—within Malaysia’s exclusive economic zone—and more than 1,700 km from China.

Under international law, a country’s territory extends up to only 370 km from its shores. Carpio said Philippine maps from 1636 to 1940, or for 340 years, “consistently show Scarborough Shoal, whether named or unnamed, as part of the Philippines.”

Spain also ceded Scarborough Shoal to the United States under the 1900 Treaty of Washington, he said.

“In sum, China’s so-called historical facts to justify its nine-dash line are glaringly inconsistent with actual historical facts, based on China’s own historical maps, constitutions and official pronouncements,” Carpio said.

“China has no historical link whatsoever to Scarborough Shoal. The rocks of Scarborough Shoal were never bequeathed to the present generation of Chinese by their ancestors because their ancestors never owned those rocks in the first place,” he said.

http://globalnation.inquirer.net/106116/justice-carpio-debunks-chinas-historical-claim.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Various Chinese scholars criticize “9-dashed line

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Various Chinese scholars criticize “9-dashed line

PANO - On May 7th, 2009, China officially asked to circulate among the United Nations state members a map that reflects the “cow-tongue” line (or the “U-shaped line” or the so-called “9-dashed line”) in the East Sea, claiming not only the islands and reefs but also the whole sea area within this line. In response to China’s recent actions in the East Sea, the world opinion is raising a question whether China is on its way to claim its sovereignty over this dotted line despite international objection.

Various Chinese scholars with certain knowledge of international law have confirmed that there exist no legal documents to verify the existence of this illegal dotted line.

Incorrect points of the “cow-tongue” line

According to Chinese scholars, the “U-shaped line” first appeared on the Location Map of the South China Sea Islands (Nanhai zhudao weizhi tu) compiled by Fu Jiaojin and Wang Xiguang and was published by Geological Bureau under China Ministry of Home Affairs in 1947.

Some people tried to hold on to the origin of this line with an aim to have an advantegous explaination for China. According to them, the “U-shaped line” was drawn by one person named Hu Jinsui in 1914. Until December 1947, an official from the Republic of China, named Bai Meichu, re-drew this line in his individual map. The 11-dotted line covered Islands of Dong Sa (Pratas), Hoang Sa (Paracel), Truong Sa (Spratly) and Trung Sa (Macclesfield Bank). However, in 1953, the 11-dotted line was adjusted into 9-dotted line. Two dots in the Tonkin Gulf was removed with no clear reason. In fact, there has so far no document featuring the accurate co-ordinate and location of the “U-shaped line” or “the 9-dashed” line been found.

Scholar, famous commentator of the online Phoenix newspaper (Hongkong, China) Xue Litai warned that China will face various difficulties and challenges from international community if it claims sovereignty over the “9-dashed” line. This scholar pointed out some incorrect points of the “cow-tongue” line.

Firstly, China itself has drawn the 11-dotted line on the map without demarcation at sea with neighbouring countries and the dashed line has received no international recognition.

Secondly, to date, China has failed to make clear that the “cow-tongue” line is the national dashed border line or traditional demarcation line at sea. Beijing has given no definition and clear longitude and latitude relating to the geological location but just drawn the dotted line on their map. That is not convincing at all.

Thirdly, if Beijing stresses that the previous 11-dotted line was the national border line that could not be violated, why after the new China was born, Beijing itself removed two dots on the map in the Tonkin Gulf. Does China consider the fixing of national border line a joke?

No reliable legal evidence

Other Chinese scholars said that the “cow-tongue” line is only the unilateral claim of China with no firm legal foundation. These scholars also have disagreed with what China has interpreted the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982 (UNCLOS 1982). This vague interpretation on the jurisdiction without mentioning geological elements of the coastal line or basic line is completely unconvincing.

Li Linghua, a researcher at China’s National Oceanographic Data and Information Centre, the author of more than 90 articles on maritime issues and the law of the sea, which were posted on different Chinese newspapers, frankly criticized wrong viewpoint on the issue relating to the East Sea and rejected the “cow-tongue” line at the seminar “The East Sea disputes, national sovereignty and international regulations” jointly organized by Tian Ze Economic Research Institute and online newspaper Sina.com on July 14th. Li Linghua stressed that “We-China had drawn the 9-dashed line with no specific longitude and latitude and legal basis”.

In his writing, “About 200-mile border map on the South China Sea (East Sea) drawn under UNCLOS” released on July 3rd, he made public a map demarcating 200-mile exclusive economic zone, concerned by nations bordering the East Sea, clearly features that areas that China has been claiming its sovereignty over basing on the “9-dashed line” are within the 200-mile exclusive economic zone of Vietnam. That article also rejected the establishment of what is called “Sansha” city by China and the international bid given by China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) for 9 blocks which entirely lie in Vietnam’s continental shelf and 200-mile exclusive economic zone.

Professor Zhang Shuguang from the University of Sichuan emphasized that the “cow-tongue” line claimed by China without any basis and international recognition is worthless. “Chinese interests need to be recognized by others. Without that recognition China has no right”.

Please read further on below link :

http://en.qdnd.vn/national-sovereignty/various-chinese-scholars-criticize-9-dashed-line/200466.html

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Youtube Videos related to West Philippine Sea

& China's Nine Dash Line.

& China's Nine Dash Line.

BBC Documentary Our World Flashpoint: South China Sea

RELATED STORIES

China's new '10-dash line map' eats into Philippine territory http://gmanetwork.com/news/story/319303/news/nation/china-s-new-10-dash-line-map-eats-into-philippine-territory

We must

recover our Scarborough Shoal from China’s illegal occupation.

The

Philippines should be more aggressive in the Spratlys

Historical Fiction –

China’s South China Sea Claim

Refuting

China’s Nine-Dash Claim

BRP Sierra

Madre at Ayungin Shoal

Ang islang

kinamkam ng Tsina

Martsa para

sa Kalayaan infront of PRC Chinese Embassy at Makati

No comments:

Post a Comment